When civil rights leader Vincent Harding visited Eastern Mennonite University 52 years ago, he knew that Mennonites had refused to own slaves during the slavery era. But he was surprised to see in 1962 that they were doing little to protest segregation and other racial injustices around them.

Harding also knew that EMU was the first historically white colleges in Virginia to admit African-American students and one of the first in the South. But those students couldn’t go into most restaurants in Harrisonburg and their parents couldn’t stay in local hotels when they came to visit their children.

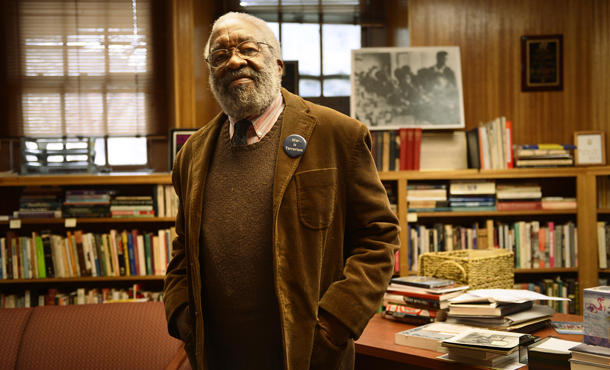

Now 82, Harding is coming back to EMU. He is the speaker for the second annual Albert Keim History Lecture Series on Feb. 26 at 7 p.m. in Martin Chapel. His topic: “Is America Possible?” He will also speak at the university chapel service earlier that day at 10 a.m. in Lehman Auditorium and at the seminary chapel the next day at 11 a.m. in Martin Chapel.

Harding was a close friend of Martin Luther King Jr. for the last 10 years of King’s life. Harding is perhaps best known as the person who drafted King’s powerful (and controversial) “Beyond Vietnam” speech, in which King announced his opposition to the Vietnam War and criticized the destructive, unfair impact of U.S. economic, political and social policies, both domestically and abroad. King delivered the speech on April 4, 1967, before a group of anti-war opinion leaders at Riverside Church in New York City.

After King’s assassination exactly a year later, Harding became the first director of the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Center in Atlanta. Later he was the senior academic advisor for the PBS television series on the civil rights movement titled “Eyes on the Prize.” In a 2008 interview with Democracy Now, Harding said that King toward the end of his life “was calling us to a way that was very difficult, a way beyond racism, a way beyond materialism and a way beyond militarism.”

Harding founded the Veterans of Hope Project, which continues to collect the stories of people who dedicated their lives to social change. The project is based at Iliff School of Theology in Denver, where he was a professor of religion and social transformation for 23 years until his retirement in 2004.

He says his current work is focused on encouraging America to become “we the people” and to create a “more perfect union” as well as participate in the making of a more just and compassionate world. His most recent book, published in 2013, is America Will Be! It is a volume of conversations on hope, freedom, and democracy between Harding and longtime Buddhist leader Daisaku Ikeda.

Harding’s other books include There Is a River – The Black Struggle for Freedom in America; Martin Luther King – The Inconvenient Hero; and Hope and History – Why We Must Share the Story of the Movement.

A native of New York City, Harding graduated in history from City College of New York in 1952, then earned a master’s degree in journalism from Columbia University in 1953, before serving two years in the U.S. Army. In 1956 he earned a master’s degree in history from the University of Chicago, followed by a doctorate in history from Chicago in 1965.

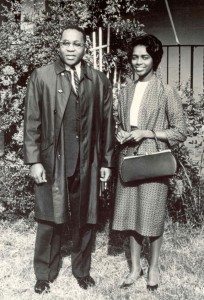

In the mid-1950s he learned about the Anabaptist/Mennonite movement of the Protestant Reformation. From 1958 to 1961, Harding was the co-pastor of Woodlawn Mennonite Church in Chicago. He often challenged Mennonites to live up to, and stand up for, their ideals about sisterhood and brotherhood socially and politically. At a conference on Mennonites and Race in Chicago in 1959, Harding met his future wife, Rosemarie Freeney. She was a 1955 sociology graduate of a Mennonite college, Goshen in Indiana, and a member of Bethel Mennonite Church in Chicago, where she worked in social services.

Vincent and Rosemarie married in 1960 and, in 1961, settled in Atlanta, Georgia, where they founded the South’s first interracial voluntary service center, Mennonite House, under the auspices of Mennonite Central Committee. The center, which was also their home (a block from Martin Luther King’s home), was an important gathering place for movement activists who found respite, hospitality, encouragement and stimulating dialogue. (Just before Rosemarie died from complications of diabetes in 2004, she noted that she had remained a member of Bethel Mennonite Church over her adult life.)

During Vincent’s first visit to EMU – and subsequent visits over the years – “he shocked and offended some members of the community, but inspired and energized others,” says EMU history professor Mark Metzler Sawin. Among the inspired were two EMU professors, John Lapp and Samuel Horst, who helped start a committee that pushed for – and won – integration of the public schools in Harrisonburg.

The Keim History Lecture Series are named for the late Albert Keim, a member of the EMU faculty from 1965 to 2000. For seven of those years he was academic dean. Keim was a popular history professor, and his courses included African-American History.