Lassana Kanneh is healing.

In 1999, along with more than 20,000 Liberian children, 11-year-old Lassana became a soldier. He was kidnapped and forced to use drugs and alcohol, destroy property, and kill in the Second Liberian Civil War from 1999 to 2003.

Now, he seeks peace for himself and his community in Liberia – a long road that has taken him to journalism and peace studies at Kent State University and most recently, to Eastern Mennonite University’s Summer Peacebuilding Institute.

“Part of my healing process is to share my story. How do I take that approach and use it in a way that might help or benefit other people?” Kanneh says.

In gaining the tools to share his story, he hopes to promote peace and non-violent action through storytelling and photography. Though his work and mentoring of war victims and perpetrators, Kanneh wants to not only continue to find forgiveness within, but also help others who are suffering “to find forgiveness for themselves, ask for forgiveness from those they have hurt, and forgive those who have offended them,” he says. “I would like to create a safe place for them to tell their stories for healing and forgiveness, and to rebuild their relationships that have been broken by domestic and political armed conflicts.”

“Young people, like me, find it difficult to reintegrate into the community,” Kanneh adds. “We have similar issues to those who have experienced sexual violence and political conflicts. It is very difficult for people returning from being soldiers to find healing for themselves.”

A ‘chance meeting on a muddy road’ changes lives

In 2006, the child soldier Kanneh was recruited again, this time through former rebel commander Christian Bethelson to leave the army and dedicate himself to promoting peace. [Bethelson is profiled in this 2011 “Yes!” magazine article.]

Bethelson, who had formerly recruited, trained and used child soldiers, was himself on a new path. A chance meeting on a muddy road with some Liberian peacebuilders eventually brought Kanneh and five other war-affected youth to American Cynthia Travis’s nonprofit peacebuilding organization, everyday gandhis, in northern Liberia.

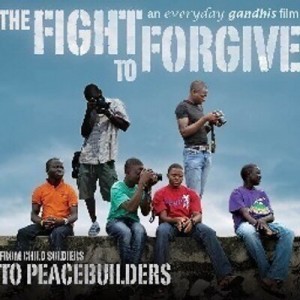

The healing journey of these six “Future Guardians for Peace,” as they’re known, is recorded in the documentary “The Fight to Forgive.” The film depicts how, after rehabilitation and support through storytelling and photography, Kanneh was able to rejoin his community, pursue his education, and speak about his experiences with the protection of the organization. Like Kanneh, the other members of the group are now in their mid-20s and working on degrees in the United States and Liberia in a variety of service-oriented fields.

Travis, who bases her organization out of California, describes her relationship with the former child soldiers as a “mother and also their friend, mentor, and source of financial and academic support.”

Supportive sponsor points young peacebuilder to SPI

It was Travis who suggested SPI to Kanneh. She first came to EMU for a winter session in 1999 (taught by Center for Justice and Peacebuilding co-founding faculty member Ron Kraybill) and then returned that summer and again in 2003, inspired by the stories and conversations of her classmates and colleagues. She says that her time at SPI helped her “form the basis for founding everyday gandhis.”

SPI provides “a mix of grassroots and institutional peacebuilders that bridges the gap between western approaches in peacebuilding and non-western cultures,” she says. Recognizing Kanneh’s interest in peacebuilding, “I realized that at SPI he would meet so many inspiring ‘kindred spirits’ who would also appreciate meeting him.”

One such opportunity was a screening of “The Fight to Forgive” at EMU’s Common Grounds. The question and answer exchange afterwards exemplified the spirit of SPI, Kanneh said later. “It’s just wonderful getting to meet people from different countries and with different experiences and backgrounds, and different perspectives when it comes to peacebuilding work and building relationships. Coming together as a group to share stories, there is much hope and inspiration, so many emotions, in a positive way.”

Applying Lessons

During Kanneh’s two sessions at SPI, he gained insights and skills he plans to apply to his future peacebuilding work. One challenge in Liberia, he says, is gender equality. The “Safe Communities and Safe Homes” course, taught by professor Carolyn Stauffer, helped him understand more about how gender roles are defined and how those roles can be detrimental for both men and women.

“In my culture, the responsibility for the man is to go out and make money and then come back home and feed the family. The female’s responsibility is to stay home and take care of the home and take care of the kids.”

The class challenged Kanneh to find ways to motivate people to push for gender equality without disrespecting the established beliefs and traditions of the community.

“If you take [gender equality] into a culture that is not familiar with it, at some point it destroys the culture. Those beliefs have been working for people for decades,” he said.

This tension lies at the heart of the peacebuilding work Kanneh wants to pursue. “How do I incorporate [my ideas] with the people’s ideas instead of me going and telling them that these are things that I think that might work in this community?”

The answer, Kanneh says, lies within empowering people to find their own solutions. As a peacebuilder, he can facilitate the discussion process; help identify leaders, talents, and gifts; and offer suggestions. However, ultimately everyone must take responsibility for their actions and decisions, he says, with the goal of creating a cohesive and sustainable society.

A first step is building the trust of his community, Kanneh said, sharing knowledge gained from a class on organizing communities for social change taught by Mark Chupp.

He says, “Part of the process of organizing communities is to explain the self-story. You have to give your self-story to people that don’t know you. How do you make the community understand that you understand their problems?”

While his classes have raised important questions, Kanneh draws strength and inspiration from his connections with other SPI members. In a way, SPI is a microcosm of the peaceful community he hopes to help build back home: full of teaching and learning and “bringing different communities together as one community.”