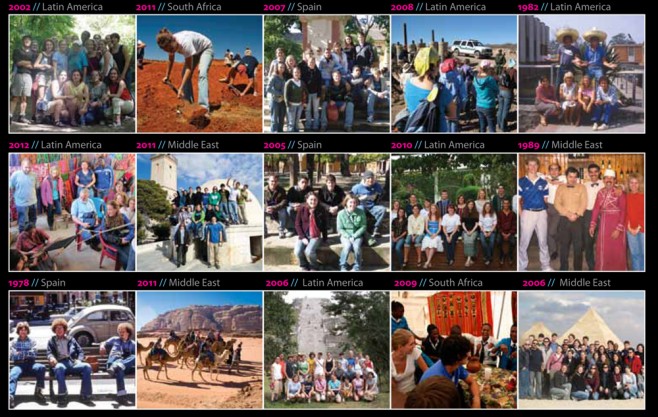

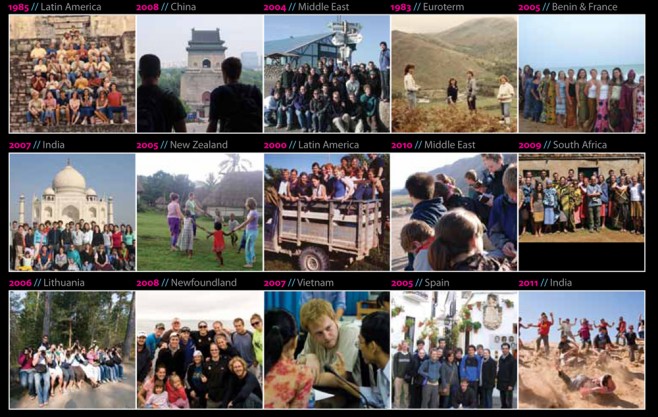

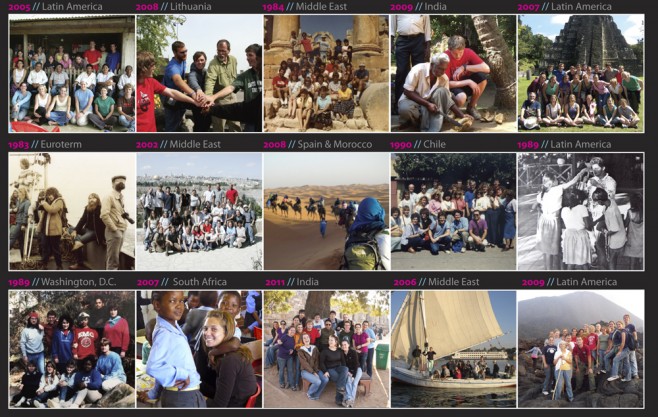

Cross-cultural study. It began as a professor’s dream for undergraduates 30 years ago and has become one of the best parts about being an EMU alumnus.

“It seems pretty odd to me to think that you could prepare someone to serve and lead in a global context without having some kind of international or other cross-cultural experience,” says President Loren Swartzendruber. “When I talk to alumni they tell me almost without fail that it was the most important part of their educational experience.”

The seeds of EMU’s cross-cultural program can be traced to the late Albert Keim ’63, a history professor and former dean. Keim won a grant in the 1970s that gave EMU the means to develop a “global village curriculum.” From 1972 to 1982, Keim and other faculty members led 10 optional trips to various locations in Europe as well as two trips to the Middle East, centering on Jerusalem. These 10 trips laid the groundwork for the cross-cultural program as it is known at EMU today. Faculty-guided study in a culture different from one’s own became mandatory for undergraduate students in 1982.

None Do It Like EMU

Requiring cross-cultural study was unprecedented among U.S. colleges 30 years ago. Even today, only two other colleges – Goucher College in Baltimore, Maryland, and Soka University of America in Aliso Viejo, California – have followed in EMU’s footsteps in integrating a cross-cultural experience into the education of every undergraduate. Instead most U.S. colleges confer credit for optional study in selected educational institutions in other countries. A handful of other liberal arts colleges devote faculty members and full-time staffers to heading foreign study each semester and summer. 1

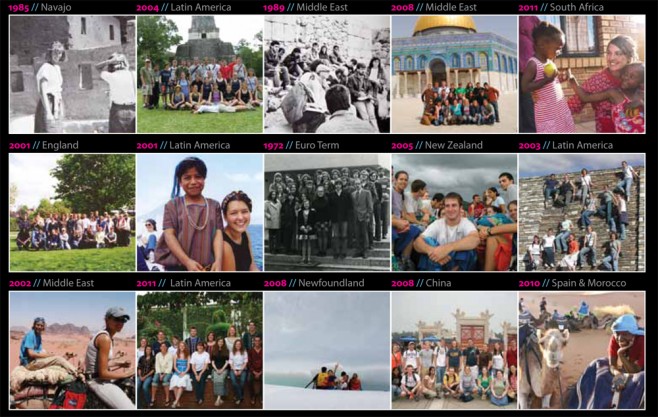

Over the years, EMU students have sojourned in more than 30 foreign locales, including the perennial favorites of Central America and the Holy Land, as well as newer destinations such as Morocco, India and Bulgaria. They have also gone to parts of the United States that would be unfamiliar to the typical EMU student, such as a Navajo reservation or coal-mining community in Kentucky. For some students, spending a semester or summer at EMU’s Washington Community Scholars’ Center, planted in the nation’s capital 36 years ago, counts as a cross-cultural experience.

“From the earliest years, we stressed having a cross-cultural experience rather than necessarily an international one,” said Vernon Jantzi ’64, who served on the EMU task force that recommended the program three decades ago.

“Cross-cultural awareness could be, and should be, fostered in our own country,” he added. “This may occur by spending time among historically marginalized groups, but it may also result from having an urban experience for the first time. You don’t have to go far away to engage with other cultures, but you need to be reflective about your experience no matter where you might go.”

The three-week summer options tend to be popular with athletes and some students in particular career paths – notably pre-med – who feel the need to stick with their usual school-year schedule. The majority of EMU students, however, go for an entire semester.

Short or long, EMU displays its preference for building a sense of community and lasting relationships by arranging for almost all of its students to do their cross-cultural as a group, guided by faculty and staff who are knowledgeable about the destination.

Importance of Bonding

The EMU approach “creates bonding and a leadership dynamic that you truly cannot create in the classroom,” said Beth Aracena, who directed the cross-cultural program from 2006 to 2012. “The professors who lead the trips make proposals in advance, detailing where they will stay and what they will see, and incorporate their own knowledge and expertise about the area as they travel.”

Over the years, mutually reinforcing ties have developed between EMU and the communities visited. Students often live in local homes, are treated as members of the family, and take part in some kind of service project, such as seeking to ease suffering in refugee camps or working to rebuild homes after a natural disaster.

One example of a unique home-stay is the environment students experience in Lesotho, a kingdom surrounded by South Africa. “The students spend time in Lesotho helping to build peace in a post-apartheid world while learning about daily life in the village,” said Aracena.

These are not mission trips in the sense of imposing religious beliefs from the outside. Instead students are asked to humbly learn from others. They are expected to gain understanding of other cultures while modeling their beliefs and values by being respectful and helpful.

Aaron Springer of the class of 2013 said people he met in the horn of South Africa gave him priceless lessons: “My family showed me generosity I had never seen before. My mother in the home stay had many children and grandchildren living in an extremely small house, with one bed. She gave up her bed for us and went and slept on the floor with her grandchildren.

“There were so many things like that they did for us. They gave us the best of everything even if it meant sacrificing. One of the things I took away from the trip was that I wanted to be more like them and be more generous. It really has such an impact on the lives of others.”

More than two decades after finishing EMU, Lloyd Gingerich ’90 says his cross-cultural trip to Central America in 1988 changed his life path.

“Things had always been easy in my life,” Gingerich says. “Christ was at the center but I was never challenged. I remember being in a refugee camp in Honduras called Mesa Grande and seeing the people living in this terrible place guarded by soldiers. The refugees started sharing their faith with us and telling us how happy they were to be alive. I saw how grateful I should be in my own life and how truly blessed I was. My faith became so much more real to me.”

Several years later Gingerich returned to Costa Rica as a relief worker with Mennonite Central Committee, rebuilding homes in a remote mountain region of Talamanca after an earthquake. Later, he lived in Costa Rica, writing for an English-language magazine and teaching in a bilingual school. He married a Costa Rican and ultimately became an elementary-school administrator in Michigan, where he has helped establish two Spanish-language immersion programs. (His photo and more details on his life can be found in this article.)

EMU’s Cross-Cultural Pioneers

“Al” Keim and his wife Leanna ’68 led EMU’s first overseas trip in 1972. Not surprisingly, the Keims led students to regions in Switzerland and Germany that were the headwaters of the Mennonite stream of Christianity.

Steve Shenk ’73 and Karen Moshier-Shenk ’73 were students on that first trip, who later became a married couple. They felt so strongly about the transformative role of that trip that decades later, in 1996, they led an EMU-sponsored summer trip to Japan.

“We definitely saw a difference between the students on our own trip [as undergrads], who were among the more adventurous on campus, and the trip we led years later,” says Karen. “The second time some of the students went mainly because it was required, and they liked that this cross-cultural was shorter and easier. But these students all had a wonderful time, and it was really a life-changing experience for them.”

Keim, dean of students during the 1970s, was the driving force for making the cross-cultural program integral to EMU’s required curriculum. The idea was not as far-fetched as it might have been at another small liberal arts college, given that the majority of EMU’s faculty had lived and worked overseas. Among the 70 percent of faculty with international credentials, religion professor Calvin Shenk ’59, sociology professor Vernon Jantzi ’64, nursing professor Ann Hershberger ’76, and music professor Ken J. Nafziger emerged as key advocates for the cross-cultural program. Shenk had lived in Ethiopia; Jantzi in Nicaragua, Costa Rica and Peru; Hershberger in Nicaragua; and Nafziger in Germany.

The task force members intended for the cross-cultural program to foster peace, tolerance and acceptance of people of different backgrounds and cultures. They saw it as a way of raising awareness of the interconnectedness of the world’s problems, including global hunger, disease and poverty, and of becoming interested in pursuing solutions.

“When Al started looking at how we could implement a cross-cultural program here, there was one thing he thought should be a major difference between EMU and other programs,” recalled Jantzi. “He was adamant that we should not reinforce the patterns between dominant powers of the world and non-dominant powers of the world. He wanted to focus on learning and having the people be our teachers.”

In a study document pertaining to the cross-cultural program, Shenk wrote: “We must respect all the cultural variations of mankind in an attempt to learn from each of them how other men have dealt with problems.” (Keim, Shenk, Jantzi, Hershberger and Nafziger are each profiled in this issue).

Getting Faculty Buy-In

Some of EMU’s old-timers smilingly say that they and other faculty members were confined to a hot, stuffy school gym during the summer of 1981 and asked to debate the pros and cons of the program before everyone agreed to the idea just to get out of the gym.

More seriously, though, legitimate objections were raised by some teachers of the physical sciences and math about the loss of momentum and knowledge if their students routinely departed for a semester. Coaches wondered how they could field competitive teams if their players came and went, missing either a sports or training season. And would students be able to graduate in four years?

The task force was charged with creating a program that would allow students to be able to choose a trip that interested them while fitting into their fields of study. A compromise emerged: some students would be permitted to fulfill their cross-cultural requirement with a three-week summer-travel program plus nine hours of cross-cultural coursework, rather than investing a full semester.

“We had a really exhilarating time debating the merits of the program, even though there was disagreement,” says Jantzi.

In a letter arguing for the program, Keim wrote: “Not only will every student at the college encounter this package of studies which incorporates our key values and commitments, but this curriculum…has special focus on biblical studies…with the notion of world service in the name of Christ.”

By the end of the summer, the faculty concurred that the cross-cultural program should become a part of the general curriculum.

A semester-long trip in the fall of 1982 of nine students to Costa Rica and Mexico marked the first study-tour that was part of the general education program. Sharon Hostetler ’80, then an adjunct faculty member in the social work department, led the group. 2

“I was happy to introduce students to the issues of peace, justice, development and the role of the U.S. in the histories and development of Costa Rica and Nicaragua,” recalls Hostetler, who is now executive director of Witness for Peace, an organization of nonviolent activists working at the grassroots to change U.S. policies and corporate practices.

Today

Today EMU’s cross-cultural program is changing and growing but it still reinforces the original goals that the founders put into place more than 30 years ago. The 2012-13 school year features trips to New Zealand, South Africa, Guatemala, Colombia, and the Middle East.

“I think one of the amazing things that is happening in the program today is that we are constantly adding new destinations to our schedule because of faculty members who show interest,” says Linda Burkholder, cross-cultural assistant director. “It really offers a vibrancy to the program and it keeps it fresh. It is not the same thing every time. Every trip is unique.”

The words that students use today to describe their experiences echo those spoken by earlier alumni, such as the Moshier-Shenks and Lloyd Gingerich. “It is so interesting to see people come back from their cross-cultural experience, because they really aren’t the same person when they return,” says Aaron Springer. Referring to his fall 2011 South Africa sojourn, “it was a life-changing experience that I wouldn’t trade for anything.”

—Rachael Keshishian (2012 spring intern, marketing and communications) & Bonnie Price Lofton, MA ’04

1. One of EMU’s sister institutions, Goshen College in Indiana, has an excellent study-service term in foreign locales that began in 1968, making it one of the earliest college-sponsored study-abroad programs in the United States. About 80 percent of Goshen’s students partake of the opportunity to spend 13 weeks with faculty members in places such as Cambodia, China, Egypt, Nicaragua, Peru, Senegal and Tanzania.

2. Sharon Hostetler first went to Costa Rica in 1974 to learn Spanish. She then worked for three years with Rosedale Mennonite Missions in Nicaragua. Joining Witness for Peace 25 years ago, Hostetler started its programs in Mexico, the Caribbean, Central America and South America. She lives in Nicaragua and holds a master’s degree in social work from Ohio State University.