By Andrew Jenner ’04

Here’s a story I heard on cross-cultural: a certain Israeli man had become disturbed with the moral implications of Israel’s military occupation of the West Bank as he grew older. After the Second Intifada began in 2000, the Israeli Army activated its reserves and this man – a reservist, like nearly every Israeli man under the age of 50 – was called back to duty in the West Bank. With a conflicted conscience, the man obeyed his orders, but vowed it would be the last time he’d agree to shoulder his gun and perform military duties no longer entirely in line with his convictions. And he was right in a twisted way, because he was killed in action during that deployment.

Here’s a story I heard on cross-cultural: a certain Israeli man had become disturbed with the moral implications of Israel’s military occupation of the West Bank as he grew older. After the Second Intifada began in 2000, the Israeli Army activated its reserves and this man – a reservist, like nearly every Israeli man under the age of 50 – was called back to duty in the West Bank. With a conflicted conscience, the man obeyed his orders, but vowed it would be the last time he’d agree to shoulder his gun and perform military duties no longer entirely in line with his convictions. And he was right in a twisted way, because he was killed in action during that deployment.

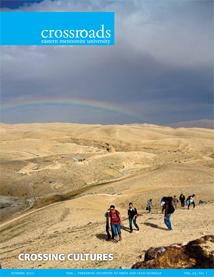

Of course, that meant I was hearing all of this second-hand from a rabbi who’d been a friend of the man who’d been called back to duty. The rabbi told this story to my entire cross-cultural group as we sat on a rocky hillside in the far north of Israel overlooking the Hula Valley. It was a stunning fall day, clear, mild, breezy and bright. I remember an Israeli flag snapping in the breeze, blinding in the sun, the swaying pine trees, the gentle sunshine on the cool stones, birds chirping, all of it underscored by that sort of wrenching sadness that lurks at the intersection of grief and death and beauty.

The cross-cultural up to that point had already put me in a precarious emotional state. We’d just spent a few weeks in Palestine, touring the refugee camps, visiting houses reduced to rubble by Israeli missiles, listening to endless Palestinian appeals against the injustice of Israeli occupation, etc., etc. And then we’d spent a few weeks in Israel, touring the Holocaust museum, driving past restaurants and bus stops where Palestinians had blown up themselves and a lot of innocent people, listening to endless Israeli appeals against the injustice of Palestinian terrorism, etc., etc. It was a dissonant, battering experience; what seemed true and right one week would be cast into doubt the next. Today’s worthy cause was tomorrow’s foolishness. I’d spread my empathies in all sorts of contrary directions. I felt like I’d been through a storm.

We’d begun that day departing by bus from the kibbutz near the Sea of Galilee where we were staying, guided by the rabbi. We rode from place to place, and we’d get out, and he’d give little talks on non-cheery aspects of the 20th century Jewish experience and modern Israeli history – a heavy, depressing day generally. And then, that afternoon, to hear the tragic story of the rabbi’s friend as we sat perched above the Hula Valley, beneath whispering pines and gentle sunshine – it was the distillation of everything that had come before, goodness and horror, beauty and fear, hope and loneliness, all existing together in that specific moment and place.

The moral of the rabbi’s story about his friend’s death surprised me, though. Like his dead friend, the rabbi wasn’t altogether comfortable with the notion of military service, and also like his dead friend, the rabbi wasn’t at ease with the notion of not coming to the armed defense of his people, repeatedly abused by unfriendly neighbors. Sometimes, he said, life forces you into uncomfortable decisions. Sometimes, he said, friends don’t come home from deployments. And all of this is part of shalom, which he defined as the fullness of human experience: a time to be born and a time to die, to kill, to heal, to scatter stones, to gather them.

At EMU, at Eastern Mennonite High School, in Mennonite Youth Fellowship, in Sunday School and all the other places up to that point where I’d received some sort of moral education, choices in life had always been framed as right vs. wrong, or good vs. evil. But there atop the cliff where the rabbi was talking about shalom, I had my first encounter with another potential moral framework for life: wrong vs. wrong. What if there are times when you’re confronted with options that all would be wrong in other contexts? What if, in a specific situation, it would be right to do wrong?

We’ve all done those little thought experiments that nibble at the edges of this concept: “If a crazy ax murderer broke into your home and began attacking your family, what would you do?” If you hold a general belief, as most EMU-affiliated people probably do, that it’s wrong to attack or injure people, and if you hold a general belief, as most EMU-affiliated people hopefully do, that it’s wrong to sit there and let ax murderers have their way with your family, you’ve kind of found yourself in a wrong vs. wrong situation. Sometimes people offer silly and insane suggestions – “share the Gospel with the ax murderer,” “give him a hug” – that purport to evade this wrong vs. wrong dilemma, but then the discussion just kind of trails off. We acknowledge the absurdity of the question. We say we hope something like that never happens to us.

There’s also the phrase “the lesser of two evils” that we employ in certain situations, like explaining why we voted the Democratic ticket. This one also subtly acknowledges that we’re faced sometimes with wrong vs. wrong situations, but not in a particularly serious sense; it’s a phrase generally used for laughs.

Life is messy, absolutes are subject to change, and truth can sound different on different days. Some people call this sort of thinking “wishy-washy,” some people would probably say it lacks “moral imagination,” some would probably say it ignores some sort of inscrutable, divine plan that some sort of inscrutable, divine being has supposedly invented for my life. And there’s probably some theological shortcoming in my understanding of what the rabbi meant by shalom. Sometimes I’m disturbed myself by the implications of this idea that Wrong and Right are entirely circumstantial. But I can’t escape it. It’s well and good and important to sit back and map out your own moral plan of action for when the ax murderers beat down the door, but it’s well and good and important to get out of your chair and step out into the muddy world, where there will be times to tear and to mend, and to weep and to laugh, love, hate.

The Middle East cross-cultural didn’t destroy my beliefs in right and wrong. The trip cut them down to size. It prepared me for compromise. It cast doubts in all sorts of directions. I hope this doesn’t sound too bleak: my experience didn’t throw me into despair, it just shifted my foundation.