“What affects one of us affects all of us, and what affects all of us affects one of us,” said Ram Bhagat, manager of school climate and culture strategy for Richmond Public Schools, and a frequent adjunct instructor at Eastern Mennonite University’s Center for Justice and Peacebuilding. His audience included 200 teachers, administrators, school staff, community organizers and others attending the Restorative Justice in Education Conference in June.

Bhagat, who holds a doctorate in educational leadership from Virginia Commonwealth University and brings rich experiences working with youth, spoke on “Building Resilience for Challenging Systemic Racism: A Restorative Practice for Youth Dealing with Urban Trauma. ”

A single event can trigger a community-wide reaction – “almost like a brush fire, or what I’ve been calling a trauma tsunami,” said Bhagat. Our education communities are connected not only through trauma, Baghat explained, but also by resilience and working towards justice: strengths that those in the RJE field aim to cultivate.

His session, along with the other 10 breakouts and two keynotes, was conducted over video conference in light of the COVID-19 pandemic.

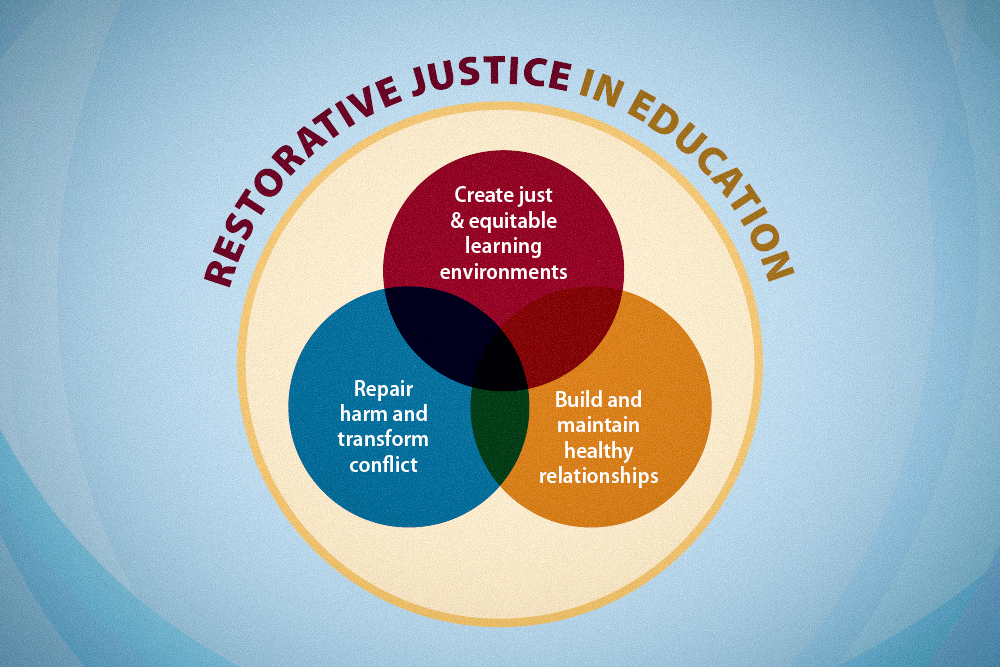

“For me, restorative justice in education has to center concepts about justice and so when inviting speakers to facilitate workshops, it is important to me that those speakers are prioritizing the work of diversity, equity, and justice,” said Professor Kathy Evans, who helped to organize the conference. Those “restorative and transformative approaches to educational justice continue to spread and grow as more and more restorative justice educators are thinking critically about what justice and equity look like for our children and youth.”

This summer marked the fifth year of the conference, which is typically held on EMU’s campus. But the virtual format welcomed participants who wouldn’t have been able to make the trip to Harrisonburg.

Last year, over 100 people participated, representing five states and 11 school districts. This year, over 200 attended from 25 states, three countries besides the U.S., and 30 public school districts or private schools. They came in their roles as teachers and professors, counselors and psychologists, circle keepers and restorative justice practitioners, attorneys and social workers.

“I think that anyone who works with youth will find meaning in the content of the conference,” Evans said. “Most people acknowledge the importance of collaboration between schools and communities and that we need all of us – educators, counselors, social workers, activists, et cetera – working together to heal our schools and transform them to sites where every child can thrive.”

One community partner in attendance was Bonnie Daley, a licensed master social worker and diversion coordinator for the Youth Services Bureau in Middletown, Conn. They coordinate an alternative justice process for youth who have been arrested for the first time. The program “allows for young people to take accountability and also to obtain support,” Daley explained.

“The shared power and ‘with’ approach in restorative work is really beautiful. It promotes solutions and healing. A restorative approach also aligns well with trauma informed and trauma responsive approaches, which are also central lenses we use in the work we do with youth and families,” said Daley.

While she gleaned useful concepts and tools from all the sessions, Daley said the opening and closing keynotes by Anita Wadhwa “were extremely powerful.”

In both sessions, Wadhwa was joined by a youth co-facilitator from Restorative Empowerment for Youth (REY), the restorative justice program she co-founded.

REY hires students who have completed the restorative justice apprenticeship program that Wadhwa started at the YES Prep Northbrook High School in northwest Houston, where “schools consist largely of students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds who are primarily Latinx,” Wadhwa said. It’s a racially and socioeconomically divided city – just across I-10, another high school “annually auctions off a prime student parking lot for $20,000.”

In the opening plenary, Wadhwa was joined by Leslie Lux – a recent graduate who has now been practicing restorative justice for four years, and who led a circle process for her own family after the death of her infant niece earlier this year. The closing keynote brought Wadhwa and Jose Lagunas, also from REY, to consider next steps in moving toward youth-led restorative justice.

The students, who begin the apprenticeship program in ninth grade, “are a blend of introverts and extroverts, high achievers and lower achievers, those who have had behavioral issues and those who haven’t,” Lux said. “But there is only one requirement: that they have the emotional maturity and openness to push themselves out of their comfort zone and be able to facilitate circles.”

“These students are no longer apprentices – they are experts. They are the best ambassadors of change for adults skeptical of the circle process,” said Wadhwa.

According to Evans, restorative justice initiatives that prioritize youth leadership have the potential to not only transform the culture of schools and districts, but also works to ensure a sustainable RJE initiative. “They have so much wisdom and experience to offer schools; we need to embrace their leadership as we seek to foster justice and equity in education.”

Yes, it is the young people who will effect change. They have seen the failures in the school, the community and the nation and they have the courage to do what is necessary to bring about equity and more opportunity. We as adults, must take the time to listen and meditate on what they are saying to us, especially parents. We have to stop thinking we have all of the answers and listen to our young peoples’ stories and react with compassion, kindness and empathy. We as a community must lock arms with our youth and advocate for their future; we will not be here forever. Let us do the work today and every day!