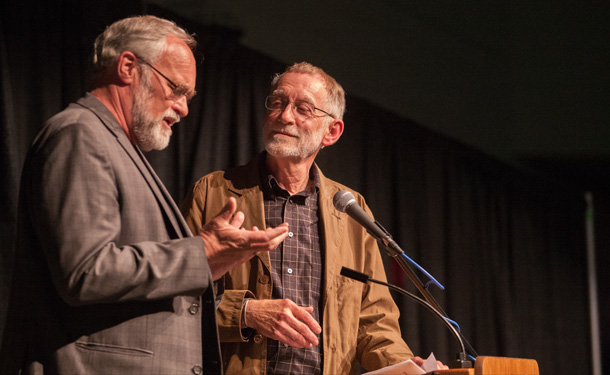

When freelance legal affairs journalist Mark Obbie wrote a six-part series on crime victims for Slate in 2015, he made sure to include Howard Zehr, professor of restorative justice at Eastern Mennonite University’s Center for Justice and Peacebuilding and co-director of the Zehr Institute for Restorative Justice.

Obbie’s sixth installation, appearing last month and titled “They Knew It Was the Right Thing to Do,” examined the “unlikely rise of restorative justice” in western New York’s Genesee County in the 1980s. Zehr, identified as the “leading thinker” of the restorative justice movement, spoke about the movement’s beginnings.

“One of the reasons the whole restorative justice field started,” Zehr says, “is we felt like victims are not just being neglected, they were being re-traumatized by this process. And we were trying to figure out how can we engage them more, give them more options, more information, meet their needs in a better way.”

The article tracks the work of Dennis Wittman and Doug Call as they worked against all odds to introduce an alternative to the “bail ‘em and jail ‘em” system of the courts that resulted in overcrowded prisons. Call was elected sheriff of the county, located midway between Buffalo and Rochester, on this platform and hired the visionary Wittman. They formed a program called Genesee Justice, then set about securing funding and winning over supporters in the justice system, government, community and beyond.

Call remained in the project for seven years, but Wittman continued for a quarter-century, throwing himself fully into the effort while introducing a variety of innovative and successful approaches with pretrial diversions, victim-offender dialogue, community meetings, and more. Genesee Justice eventually ran into challenges as funding dried up and some of the original vision faded, especially after Wittman’s retirement in 2005. The program continues today, but in a reduced form.

Zehr says in the article that, despite many positive attributes, the restorative justice movement has struggled for recognition and implementation on a large scale due to a “firmly entrenched punitive culture” and the lack of a central organization.

He also notes that such movements are often eventually “co-opted” by government agencies and others, resulting in diluted or distorted forms of restorative justice. Charismatic and well connected individuals like Wittman are often the impetus for initial change, Zehr says, and continuing their work after a leadership change can often be a challenge. (“A clear grounding in principles and values can help avoid this tendency,” Zehr commented after reading the piece.)

Nonetheless, Obbie thought restorative justice is an important area to examine during his investigation, which was funded by a Soros Justice Media Fellowship. In an overview of the series, the author writes: “We owe it to victims to understand them and their experience much more deeply than we do when we shed a tear, rage at the ‘senseless’ crime that befell them, and then move in, secure in the belief that excessive punishment is the primary response needed. And we must offer victims more options than just indulging their first reactions.”

The Zehr Institute is in the midst of a three-year project, funded by Porticus, to assess the field and map its future. A May 2015 consultation attended by 36 global leaders was the first step. A conference titled “Restorative Justice in Motion: Building Movement” will be June 14-16 at EMU.

Both EMU and EMU Lancaster offer a graduate certificate in restorative justice, and a master’s degree and graduate certificate in restorative justice in education.