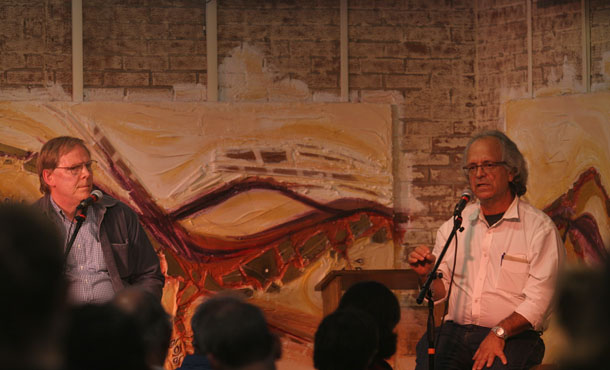

In front of a packed audience at the Common Grounds coffeehouse, an Israeli philosopher and a Mennonite theologian sat down to debate the ethics of pacifism and violence, approaching the issue from an unconventional angle: Is it unethical not to use violence as a last resort to resist evil?

Moshe Shner, a professor of Jewish philosophy at Oranim Academic College in Israel, spoke about his mother’s participation as a paramedic in a Jewish partisan group that violently resisted Nazi Germany during World War II. Shner grew up on an Israeli kibbutz surrounded by the children of other veterans of the partisan movement, feeling pride that they had “done something” to stand up for themselves.

“It doesn’t mean that we love war or that we love bloodshed,” said Shner. But it does mean, he continued, that sometimes, when all other options have been exhausted and when facing a truly implacable enemy causing harm to innocent people, using violence to try to prevent further harm is the ethical choice.

“Violence is bad. Violence is ugly … but in the end, we have responsibility to ourselves and our society and we have to do something that will stop [other] violence,” said Shner.

Unethical to acquiesce to harm

Ted Grimsrud, an Eastern Mennonite University theology professor who has written extensively on the subject of pacifism, agreed with Shner that standing aside while innocent people are being harmed is unethical. As a conviction that each human life is precious, pacifism, Grimsrud said, requires nonviolent resistance to protect others from harm. But he argued that eventually resorting to violence – and later “valorizing” that violence, as he implied Shner does in the case of the Jewish partisans – makes violence “much more acceptable” the next time a conflict arises.

Grimsrud also said that the lesson of World War II should be that violence doesn’t work, as indicated by the Allies’ failure to stop the Holocaust from happening.

“The war was essentially a failure when it came to preventing harm-doing to Europe’s Jews,” he said.

He pointed out that the most successful instances of saving Jewish lives during the war – the “rescue” of Danish Jews to Sweden and the safe haven created in the French village of Le Chambon – were forms of nonviolent resistance.

Shner simply disagreed with Grimsrud’s stance on the efficacy of violence during World War II. It wasn’t philosophers or theologians or intellectuals who stopped Nazi Germany, he said, it was General Patton and General Zhukov who stopped Nazi Germany and saved the Jews who were still alive when the Allied armies were finally successful.

Force necessary at times?

“There are moments in life – you don’t like them and you hope they don’t come – when you have to use force,” Shner said.

By the end of their debate, Shner and Grimsrud had agreed in general that we are ethically obligated to nonviolently resist people or things causing harm to other people. They then began to split finer and finer hairs over the appropriate response to a harm-doer who doesn’t stop when confronted nonviolently, moving through an increasingly aggressive set of nonlethal violent tactics up to, finally, lethal violence (which Shner said is justified when all other options are exhausted).

“The line that I wouldn’t want to cross is killing somebody,” said Grimsrud, acknowledging the difficulty of the issue. “In a fundamental sense, I think violence is always wrong … but it was good that the Nazis were defeated.”

Shner’s visit to EMU was arranged by Linford Stutzman, a professor of culture and mission who regularly leads semester-long cross-cultural study groups to the Middle East. Stutzman first met Shner more than a decade ago when Shner made a similar presentation to a group of EMU undergraduates in Israel, as he has regularly been doing ever since.

“His position on the ethics of ‘non-pacifism’ is intriguing. We need that to test our own convictions,” said Stutzman, who said that Shner’s position, if nothing else, compels pacifists to empathize with individual traditions and experiences that lead people to non-pacifist stances.

Stutzman also said that the question of pacifism’s efficacy, which consumed much of the debate, isn’t central to his thinking on the subject. Violence clearly is effective, and claiming pacifist convictions is easy in the comfortable Shenandoah Valley, Stutzman continued. But Jesus, he said, wasn’t in a position of personal security or comfort when he taught his followers to love their enemies.

Called to pacifism as a follower of Jesus

“I’m not a pacifist because I think it will protect me [or others]. I’m a pacifist because I believe that’s what Jesus calls us to do.”

Elise Sauder, a junior who attended the debate, came because she’s sometimes wondered whether her own pacifist convictions are always ethical.

“Although I believe that Moshe had really good points, my thinking is that things always come back to my faith in God, that He will protect me. If somebody was attacking me, I believe in my heart that I know where I’m going,” said Sauder, who was also a student on Stutzman’s cross-cultural to the Middle East in the spring of 2013.

And when it comes to the ethics of using violence – or not – to prevent harm being inflicted on someone else?

Much harder question, Sauder acknowledged, as other members of the audience clustered around Grimsrud and Shner to continue the discussion past its allotted hour and a half – not enough time to change peoples’ minds, it seemed, but plenty to get them thinking hard about difficult questions.

Excellent balanced summary. Thanks.