A 1983 talk by Professor Calvin E. Shenk ’59

Early 1980s undergrads Peter Gabriel '83 and Dale Ressler '84 chat with Calvin Shenk, then professor of church studies. Photograph courtesy of EMU archives.

Twenty-two years ago, Marie and I were on our way to Ethiopia by freighter. It took us a month to cross the Atlantic, the Mediterranean, the Suez Canal and the Red Sea. We soon learned that the geographical distance we crossed was small compared to the cultural difference.

In the next 14 years we crossed over and came back three times. We learned to adjust to a new culture and we also learned to evaluate our own. We rejected values of both cultures and we accepted values of both. We became third culture persons. Those were life-transforming years.

John Dunne of Notre Dame, in a book called The Way of all the Earth, speaks of passing over and coming back. He describes passing over as a shifting of standpoint. One goes over to the standpoint of another culture, another way of life and another religion. This is followed by coming back with new insights to one’s own culture, way of life and religion.

Growth demands that we cross over into new experiences, new points of view, new worlds. Since we are guests, we can’t completely cross over. But when we come back, we are different persons. Our vision is enlarged. We ask new questions and have new concerns and new priorities.

This kind of experience highlights the essence of education. American education gets into ruts. We harden the categories. We forget that there are other cultural models by which to interpret the world. When we emphasize American strength in time of insecurity, we become very ethnocentric.

Many of us are uneasy with the Col. Qaddafi’s, the Ayatollah Khomeini’s and the Soviet Unions. We are justifiably troubled with Qaddafi’s role in the Middle East and North Africa. We have reason to be alarmed at Khomeini’s action against dissidents in Iran. We are rightfully angry at the shooting down of a Korean plane.

But while we are troubled, alarmed and angry we must also try to understand others’ fears and hostility toward us. How do others see us in South Africa and Latin America? We must not use the breakdown of our relationship with the Soviet Union only to reinforce preconceived opinions. We are not always right, and neither are we always wrong. But without a global perspective we can’t even make judgments about right and wrong.

We believe that the job of mediating between cultures is the task of higher education. As a Christian liberal arts college, we have reasons for considering this a high priority.

We believe this is part of the creation mandate. We are concerned for our world and human relationships. We believe in the international character of the Kingdom of God. We believe in a cosmic Christ for the “global village” — Marshall McLuhan’s term for a shrinking world.

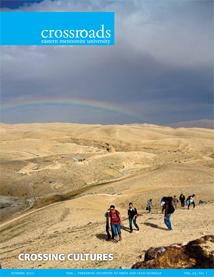

In the past EMC has stressed world mission, development, and peace and justice. We have encouraged students to study in Costa Rica, Europe and the Middle East. We have sent students to Mexico City, New York and Washington. We now believe the time has come to say that all students ought to do this. We structure this as we do classes on writing, computers and accounting.

We are asking that every student have nine semester hours of cross-cultural courses. At least three must be taken in another cultural setting. This can be done in a semester in Europe, the Middle East or Latin America or in three weeks in rural or urban North American settings like Mississippi and Philadelphia.

I believe both kinds of experiences are valid. Marie and I have experienced the community of learning in leading a 10-week Jerusalem Term. This summer we discovered possibilities of learning in a month-long pilgrimage to East Asia.

It is not tourism, not dabbling, that we are encouraging. It is something akin to being a pilgrim. Pilgrims are serious seekers. We want students and faculty to be immersed in a culture, to live close to people. We are concerned that students become more globally aware and learn to understand cross-cultural dynamics.

In addition, we want students to develop appreciation for the presence and role of the church in the world. “How does the cosmic Christ relate to the learning and experience of people in specific cultural settings in the global village?” we ask.

Perhaps we can develop an educational model similar to the Tao Fung Shan Study Center located on a mountain overlooking the coastline of Hong Kong. There is an octagonal chapel looking much like a Buddhist pagoda. The symbol of this center is the cross rising out of the lotus flower (symbol of Buddhism). Here is symbolized a sympathetic understanding but also an encounter between the Buddhist culture and the Christian faith. Grace can fulfill and not just destroy nature.

We at EMC are in the process of developing models, if not centers, where such interaction can occur. We want to see what the cross looks like in different cultural settings. We want to develop a community of faculty and students who are crossing over and coming back.

Cross-cultural experience must be more than a parenthesis in our lives. Coming back is as important as crossing over. It is unfortunate if we come back the same as we went. Coming back should force us to work seriously at reshaping our values.

This kind of education will be both painful and enjoyable. The results will not always be predictable. We will experience anger and exhilaration, depression and vision. But growth will occur, and that is what college is for. Such education will make us better citizens of the global village and better members of God’s international kingdom, the church.

This is not just a dream. It can become reality. If it is possible for people in their middle 40s to be transformed, it is possible for college students to change.

Here is one example of how this happened for me this summer in East Asia.

We made our pilgrimage to Hiroshima. How tragic that event! How horrible the memory! More than 200,000 people died as a result of a bomb dropped by one from our culture; 5,000 atomic bomb orphans still live there. Almost everyone living in Hiroshima lost a relative. As we were eating the evening meal as guests of a Japanese widow, she very politely told us that her uncle and aunt perished in that explosion. I wished that all world leaders could go there. I wanted the president of the United States to visit.

Words don’t explain this stupidity. Words can so easily rationalize it. I’m amazed at how the Japanese have forgiven. Peace is high on their agenda. I’m glad the Quakers are in Hiroshima working for peace. I’m glad a Mennonite Church has recently emerged there.

The mayor of Hiroshima has said: “It is time for all of us to look at the issue the human race. Only then will it be possible to overcome confrontations between ideas, creeds and political systems and build a path toward peace based on cooperation and interdependence.”

“Global viewpoint,” “survival of the human race,” “cooperation,” “interdependence” and “peace.” Are these not sufficient reasons for crossing over and coming back?

* * * *

When he gave this talk to a group of EMU supporters on Sept. 24, 1983, Calvin Shenk was chairman of the Bible and religion department. He is now professor emeritus and lives at Virginia Mennonite Retirement Community. His wife Marie died in 2010.