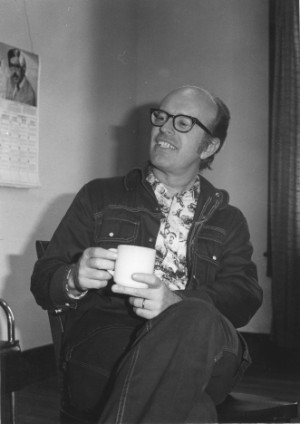

Sociologist Vernon Jantzi in an early 1980s photo. Photograph courtesy of EMU archives

EMU’s cross-cultural program is intentionally different from that of almost every college in America, says Vernon Jantzi ’64, who became a faculty member at EMU after earning his PhD in the sociology of development from Cornell University in 1975.

Jantzi, who has held a number of key administrative positions at EMU (and who passed up a chance to work at Harvard to come to EMU), was one of the founding faculty members of EMU’s Center for Justice and Peacebuilding and served as its second director for seven years, after its founder John Paul Lederach.

“We have slightly different ways of measuring success and what a cross-cultural program gives back to the students than a secular college or university,” explains Jantzi. “Our cross-cultural is not just an education for the intellect but it is a life-changing experience that is spiritual and changes students’ entire educational experience.”

EMU’s aims to improve the communities in which students spend time, while cultivating a sense of humble respect in the students for the wisdom, knowledge, and culture of the people they meet.

“There certainly are benefits in the professional world in doing a cross-cultural,” says Jantzi, “but our focus is on how it is going to change your life and outlook. This has been the goal since the program was implemented in 1982.”

As a case in point, Jantzi wrote his master’s thesis on Chile, but had never actually been to that country before leading a cross-cultural trip there in 1990. “I wrote my paper about how the government influences the Pentecostal Church. But when we actually went to Chile I saw a lot of that information in a different way.”

One of Jantzi’s criteria for a successful trip is for students to live within typical households. “I want students to be exposed to the cross-generational experience in that country and the things involved in family life in that country. . . .

“[In Chile] some of the students even lived with families who had been tortured or had family members killed by the military. They experienced families with very different political views than they had ever seen before. Some things can’t be learned from a book.”

Jantzi and his wife, Dorothy ’62, lived over 12 years in Latin America, notably Costa Rica, Nicaragua and Peru; he has been a consultant on development and restorative justice matters in a number of other countries.

(The Jantzis’ son, Terry ’87, also earned a PhD from Cornell in international and community development. Fluent in Spanish, he taught full-time at EMU from 1999 to 2010 and co-led, with his wife Elizabeth, a Peru cross-cultural in 2007. He then moved to international work with World Vision.)

In the mid-1980s, Jantzi spoke wherever he could – in churches, other universities, Congressional hearings – on the disastrous impact of U.S. military support for the “Contra” militias in Nicaragua. Alternatively, Jantzi advocated U.S. support for dialogue between the opposing factions and for development efforts to alleviate poverty.

At the time, he expressed amazement at Washington’s ignorance about Central America, adding that Mennonite Central Committee volunteers working there at the grassroots seemed to be much better informed than the policymakers were.

Jantzi, who speaks Portuguese and German in addition to Spanish, led a nationwide adult literacy program in Nicaragua in the late 1960s. In the early 1980s in Costa Rica, he was director of Cornell University’s program on worker-owned and -managed enterprises in collaboration with the Instituto de Tierras y Colonizacion. In New Zealand in the last decade, Jantzi helped found peace centers at two universities.

In 2009, Jantzi was tapped to coordinate a feasibility study for the now-established Center for Interfaith Engagement, under which EMU invites Christians, Jews, Muslims and others from diverse streams to build relationships based on mutual respect and understanding. He now works as a facilitator for EMU’s Strategies for Trauma Awareness and Resilience (better known as “STAR”).

Reflecting on his early-career decision to pass up a position at the Harvard International Institute of Development, Jantzi says, “It was a struggle, not an easy choice, because there was sacrifice involved.

“But EMU has been good. I estimate that 75 to 80 percent of faculty members have made those same kinds of choices. We choose to stay because there’s something about EMU that you don’t find anywhere else. It’s worth the sacrifice.”

—Rachael Keshishian & Bonnie Price Lofton