Sarah Jones ’08 starts her day with the sun, collecting eggs. And while she does live on a farm, the eggs she collects are actually human oocytes, for her work as an embryologist at the Markham Fertility Centre just north of Toronto, Canada.

Patients visit the center for a variety of services, including Jones’s specialty: in vitro fertilization. Her days progress through every step of the process, from the small surgical procedure to collect a patient’s oocytes first thing in the morning, to washing a sperm sample, to tending the incubating eggs, sperm, and embryos.

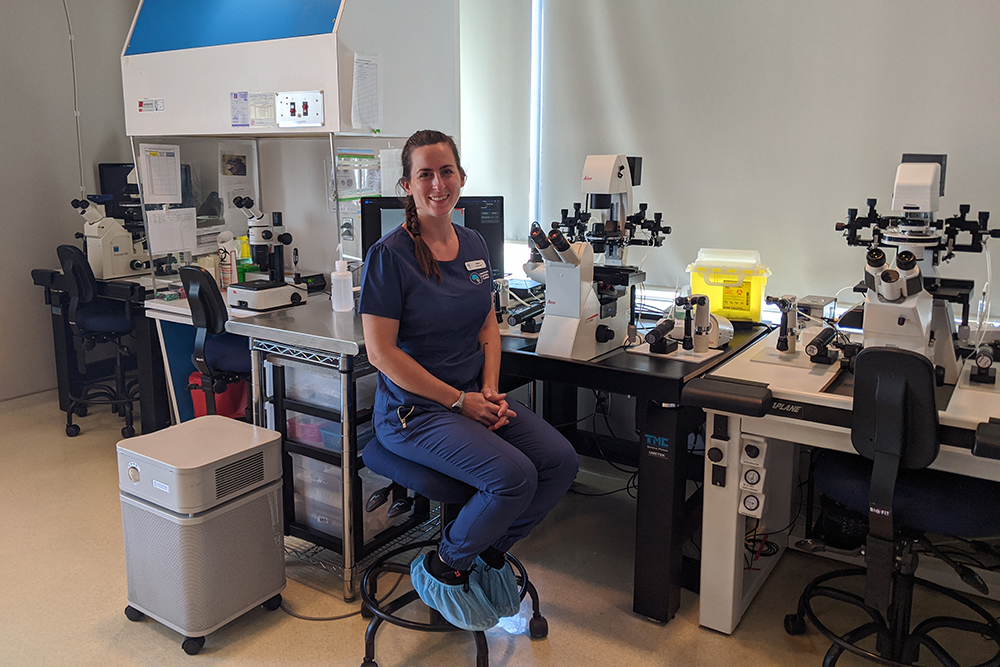

One of her responsibilities that requires an incredible amount of finesse is direct insemination: by using a miniscule needle attached to a microscope, Jones can pick up one individual sperm cell and inject it into an egg, thus increasing the chance of fertilization. The equipment is operated by joysticks, which through hydraulic tubing, convert the movement of Jones’s hands into the micro-movement of the needle.

“I kind of think of it a bit as like a video game,” Jones said. “It still kind of amazes me.” A big leg up to doing this work came from research projects Jones completed as a pre-med undergraduate at Eastern Mennonite University, which included working with micro-manipulators similar to those she uses now. She remembers Professors Greta Ann Herin and Roman Miller for being “wonderful supporters.”

Jones went on to earn a master’s degree in biology with a focus in neuroscience at York University in Toronto. By then, she knew that she’d prefer working in a clinical lab setting rather than becoming a physician, so she could be directly involved with a patient’s care but still “behind the scenes.” She started working at the fertility clinic shortly after graduating eight years ago.

“This field is just so fascinating. It feels like a really great fit,” Jones said. She says it’s miraculous how much we now know about embryo development “so that we can recreate it in the lab and support families,” including those outside the stereotypical model, like single parents and same-sex couples.

“That’s really important to me,” she said.

The gametes are cultured in the lab for seven days, with 15 to 20 patients’ potential embryos in the lab at a given time, Jones said. She checks on the embryos throughout her day as they sit in petri dishes, which are filled with a special liquid that contains proteins and sugars. Their incubators are kept precisely at body temperature, and a gas mixture is pumped in to maintain a pH environment similar to that of the Fallopian tubes.

Some patients choose to have their embryos genetically tested, “to ensure that we have a … genetically normal embryo for transfer, to increase the chance of a pregnancy in the future,” Jones said. The embryos are then frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored until the test results come back – then they can be thawed out one at a time to be transferred at the right moment during a patient’s menstrual cycle.

About 50% of the embryos in their lab turn out “normal” – the others, if they had developed naturally in the patient’s body, would likely have passed through the uterus without implanting, and the patient would have had a normal period without ever knowing fertilization had taken place.

“That happens a lot of the time in nature, and we just have no idea,” Jones said. By testing the embryos beforehand, “it increases their positive pregnancy rate by about 15% … in our lab, it’s a great tool to help us give them just a bit better chance of achieving that pregnancy.”

In addition to making parenthood more accessible for those who want it most, Jones also hopes her work helps to ease the stigma around infertility.

“It’s a real thing that happens to so many couples,” Jones said.

So good to read about the career path of a “star” undergraduate EMU biology major who consistently did excellent work. May God bless you in your work and labor, Sarah. Shalom. Roman Miller

The issue with in vitro fertilization and similar fertility procedures is that it treats children as a commodity to be obtained. Disposing of embryos, which are living humans, because they are not genetically desirable, as well as the selective abortions that often occur following in vitro fertilization, are blatant acts of evil that result when people decide that they want to have a child at any cost – including killing some of their own children in the process.