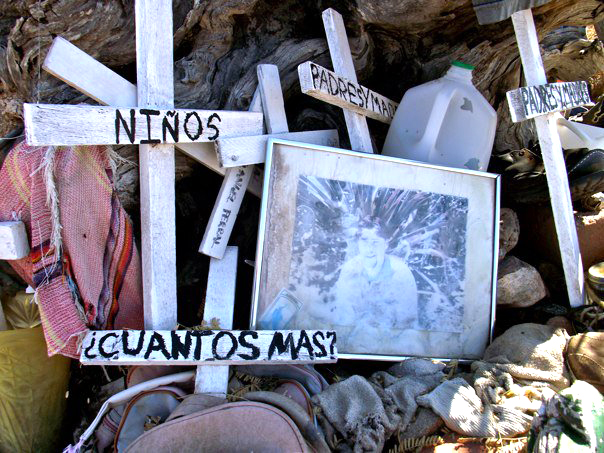

Since 2003, over 2,000 desperate people have died trying to cross the harsh Sonoran Desert between Mexico and the southwest United States. This continuous death toll prompted the foundation of Tucson Samaritans, a humanitarian group which has drawn in Isabel Allen, an alumnus of EMU’s STAR program, and senior nursing student Zach Coverdale.

Allen is the sort of activist who will give someone the lunch out of her knapsack – quite literally. Trained in Strategies for Trauma Awareness and Resilience (STAR) in 2007, she works with the Tucson Samaritans to provide food, water, emergency medical assistance, and trauma recovery to people crossing the Sonoran Desert around the Arizona/Mexico border. These Samaritans routinely go into the desert to refill “water drops,” supplying emergency water and food for those crossing the treacherous desert.

During one foray in late 2014, Allen’s group came across two young men from Central America who had been apprehended by the Border Patrol. Having already deposited all their bulk supplies at water drops, Allen and another volunteer gave their own lunches to the apprehended men, along with water that remained from the drops.

Coverdale has also trekked into the desert with Tucson Samaritans. In high school, he participated in their 14-hour training session, and regularly joined water drop teams. One time, while walking along a migrant trail, his team found their water bottles punctured and scattered in the scrub. Slogans like “go border patrol,” “my dogs like bottled water,” and “stop illegal immigration and those who support it” were written on them in marker. Such opposition to migrant aid programs is common in Arizona.

Often, the Samaritans restock water drops without ever seeing their beneficiaries. However, when they do, one branch of the organization is medical intervention.

Allen explains that, in extreme situations, they must sometimes call the Border Patrol as a last resort to help someone who is very sick. “We stay with the person until help arrives, and usually travel with a nurse, or one is on call at the time.”

Her passion for this work stems from ten years of activism work in Latin America, becoming familiar with the violence and hardship that migrants face.

Current migrants, including children and elderly, are fleeing a variety of problems; political upheaval, gang and cartel violence, poverty, forced displacement, and de facto martial law prompt many Central Americans to seek stability elsewhere. “For a short time, I actually assisted with migrant families who were ‘cleared’ for entry at the border, and we heard many stories of families who had fathers assassinated in these countries,” says Allen

Allen, whose birth name is Sally, is currently training to become a DACA interviewer – a person knowledgeable in immigration legislation who assists applicants for U.S. residency or citizenship with the newly reformed process. This assistance includes answering migrants’ questions and helping them prepare documentation. For the most part, Allen says, migrants are trying to find family already living in the States. The stakes of reunion, however, are high.

“These families and migrants are very traumatized because of the risks they run crossing the border,” as well as the conditions that caused them to leave their homelands, says Allen. “The land is very difficult to cross, and they often lose their way. Others become very ill from extreme heat or cold, and die in the desert.”

Coverdale recounts another water drop during the winter, during an unusually cold, 12-degree day. He found out later that several migrants had died that night due to exposure. The desert is unforgiving enough at its average temperatures – “it’s really easy to get lost and turned around,” says Coverdale, “especially if you’re dehydrated and delirious.”

The many miles Samaritan teams drive to water drops are daunting enough in vehicles. “That vastness represents days and days of travel for people who are fleeing systemic violence and oppression.”

A leather shoe smaller than an adult’s hand gives Coverdale a tangible reminder of migrants’ pilgrimages. He found it, filled with spiders and dirt, next to a photo of two boys and a laminated card depicting the Virgin Mary.

“I still have it, and I still think about whose foot that was on last. . . did they make it?” Physical remnants such as those remind Coverdale of the reality of people’s struggles amidst broader discussions of policy and politics. “That made it very real for me,” he says. “It was very sobering.”

I’ve also worked on the border, but with a different organization, No More Deaths. The trauma I saw in the migrants faces, the vastness of the desert and the remnants of people’s lives left behind on the trail were truly eye-opening, astonishing, and deep. Thank you for sharing your story, and know that others are sharing your experience with you. I’m so glad to see that members of the Eastern Mennonite University community are making a lasting difference in people’s lives by doing such strong and sometimes polarized work.