A digital collection of writings by humanitarian and armed conflict researcher Larry Minear and his colleagues now resides with the Eastern Mennonite University (EMU) library. The works include 15 books and various studies, trip reports, and thematic reviews on conflicts and aid work in Africa, the Balkans, the Middle East, Latin America, and the Caribbean.

The choice of EMU to house the collection of work by Minear and colleagues, the author explains, “seems apt given the enduring interest of Mennonites in factors, both local and beyond, that make for peace.”

Scholars and practitioners looking into “the convergence between peace and security and humanitarian assistance” will take particular interest in the collection, Minear said.

The collection is a work in progress and additional materials will be added as they become available or as copyright permissions are granted, said Marci Frederick, director of libraries at EMU.

Jayne Docherty, executive director of the Center for Justice and Peacebuilding at EMU, praised Minear as a pioneer of seeing “many ways of responding to human needs as a part of what must be done to build positive peace, not just put an end to overt violence.”

“The way he and his colleagues connected humanitarian action and peacebuilding, the way he modeled the values of the work, and the hard-to-find archives from people who were ‘in the room where it happened’ for some interesting times” make this collection particularly valuable, Docherty said.

The collection also features a number of reports by the Humanitarianism & War Project, an independent policy research initiative based first at Brown University and then Tufts University. The value of the Sudan report for aid officials led to a request from the agencies for additional country reviews.

For this initiative, Minear and colleagues traveled to Africa to study Operation Lifeline Sudan in 1989 – an undertaking by the United Nations and non-governmental organizations to bring aid to the war- and drought-besieged country.

“Operation Lifeline Sudan is a story of a massive effort, led by the UN but building on and expanding the work of others, to provide aid to people under siege,” Minear wrote in 1990, in the foreword to Humanitarianism under siege: a critical review of Operation Lifeline Sudan. He continues,

The challenge was to reach more than two million people throughout the southern Sudan … Lifeline is also a story of the aid itself and of those providing it coming under siege as the warring parties threw up obstacles to reaching those in need. Difficulties notwithstanding, Lifeline succeeded in helping avoid widespread starvation and displacement in 1989.

Minear operated out of Nairobi, Kenya, during this research. It was there that he forged working relationships with colleagues associated with the peace churches. Thirty years later, Minear said that as he was looking for a home for the work that was accomplished, “it seemed only logical that we would build on what we had already done in the region.”

Minear was first drawn to this field from working as a teacher in suburban Chicago in the late 1960s, while the Nigerian Civil War raged on. His students prepared presentations on the conflict, and Minear then led them in charity drives – collecting school supplies and other necessities for Nigerian families.

“This then became an ongoing activity for me at the school,” Minear explained, “which I then carried forward in my professional life. Different conflicts, different settings, different techniques, but basically the same issue emerged: How do you protect humanitarian values in settings where warfare is taking its toll?”

The collection includes research on other crises that were studied by the project:

- Conflicts in Afghanistan, Burundi, Colombia, Liberia, Northern Uganda, and The Sudan in the early to mid-2000s, which are analyzed in a 2015 report for the Feinstein International Center,

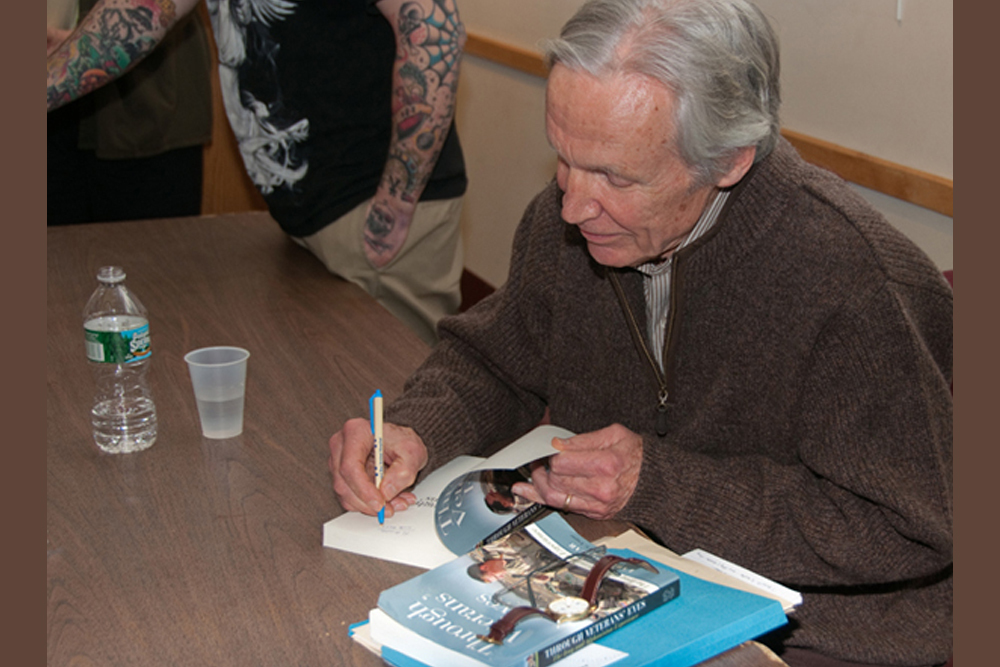

- The United States’ Global War on Terror in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the impacts on U.S. veterans, as told in a report for the Feinstein International Center and a collection of personal narratives titled Through Veterans’ Eyes: the Iraq and Afghanistan Experience.

- Famine in sub-Saharan Africa, refugee crises such as that of the Afghans in Pakistan, various conflicts in Lebanon and the Middle East, the Nicaraguan Revolution, and other Central American conflicts of the 1980s, as discussed in the book Helping people in an age of conflict: toward a new professionalism in U.S. voluntary humanitarian assistance (Interaction, 1988).

- Military personnel sent to the aid of civilian populations during the Rwandan genocide of 1994, published in the study Soldiers to the Rescue: Humanitarian Lessons from Rwanda.

Parallel to these country studies, Minear did his own reflections to pursue issues in greater detail.

Researchers and aid practitioners will have “grist for their mills to elaborate on the earlier experiences,” said Minear.