The effects of tarantula toxins on the nervous system is a hot topic in the neurology field today. Enter Charlie Good: a rising senior majoring in chemistry at Eastern Mennonite University who is interning at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, Maryland.

Good works in the molecular physiology and biophysics section under the guidance of principal investigator Kenton J. Swartz ’86 and postdoctoral fellow Kanchan Gupta. They are synthesizing variants of a toxin found in the venom of the Chinese earth tiger tarantula, and studying how those toxins interact with ion channels. The research aims to provide knowledge about how toxins cause ion channels to close and open, thereby shining light on the channel mechanisms.

Good began his internship in January while on a spring cross-cultural semester with the Washington Community Scholar’s Center (WCSC). When Swartz urged him to think about extending his internship through the summer, Good then applied for and was accepted into the NIH Summer Internship Program. While this program is competitive, with only about 1,000 applicants accepted from more than 6,300 applications in 2013, NIH scientists select their own interns. Good’s placement through WCSC and his work begun with Swartz in the spring set the stage for his continued research.

Lab work under Harvard-trained neurobiologist

One of Good’s biggest challenges, he says, has been learning about the field of biophysics and the specific biochemical, molecular biological and biophysical techniques used in Swartz’s lab to investigate toxins and ion channels. His principal investigator, Swartz – who double-majored in chemistry and biology at EMU and earned his PhD in neurobiology at Harvard University in 1992 – has been working in the field for years, including postdoctoral training at Harvard Medical School.

Good explains the basics of his research in layman’s terms: Ion channels are a part of neuron, muscle, and touch sensor cells which can generate electrical signals, allowing cells across the body to communicate. When one ion channel opens, charged ions rush out of the cell, creating an electrical signal. This causes adjacent ion channels to open, making a chain reaction known as the “action potential.”

“The action potential is the fundamental means for communication within our bodies because of the speed at which a signal travels,” explains Good. “For example, if you touch a hot stove, ion channels open in response to this stimulus, sending an electrical signal to your brain. Then your brain sends an electrical signal back to quickly remove your hand.”

The first two months in the lab were arduous, Good says. He’s no stranger to detail-oriented and sometimes frustrating work, having spent the previous summer at North Dakota State University working with a graduate student on biomass carbohydrates. But biophysics is a new field to him.

“There was a lot of failure at the outset,” says Good. “Instruments failed, I made mistakes, and the project did not seem to move forward. Yet the reward was just around the corner.”

Finally, a breakthrough came, and Good progressed from synthesis on to “more interesting experiments.”

“That was also the point when I realized that I wasn’t as bad at lab work as I had begun to imagine,” says Good.

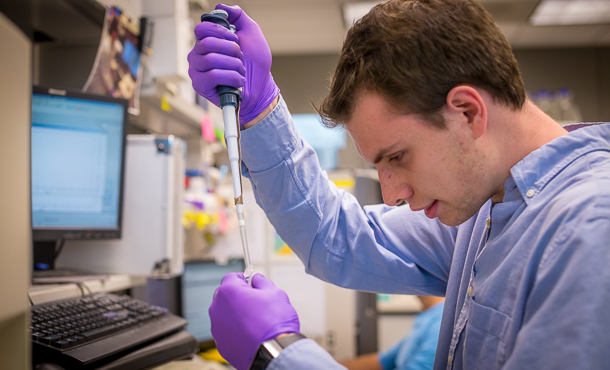

To begin synthesizing the toxin, Good programs instruments to load amino acid cartridges in the proper order, producing an impure toxin in 36 hours. This is just step one of a long process.

“Some mornings, I have experiments that need immediate attention because of their length,” says Good. “For example, one chemical reaction takes four to six hours to complete, followed by a long separation step and freeze-drying, which I set up to run overnight. After work on these days, I’m both physically and mentally exhausted.”

Research guides career exploration

On days that he isn’t tending to chemical reactions or programming lab instruments, Good attends scientific NIH Summer Internship Program presentations, reads literature, plans for future experiments, and writes.

During the spring semester, he tapped into the social side of WCSC, exploring Washington D.C. and spending time at the group house.

“Some of us went to see [singer-songwriter] Andy Grammer, checked out a Wizards game, and rented paddleboats on the Tidal Basin to view the cherry blossoms.”

When his WCSC semester concluded, Good moved into other housing. His internship ends in August, at which point he’ll return to EMU for his final year.

In addition to the South Dakota research, Good has worked with chemistry professor Matthew Siderhurst to identify noni fruit’s chemical make-up. Adding eight months of research at NIH to his research portfolio has been an invaluable experience, Good says. The internship has given him a better understanding of the process of original research, and piqued his interest in the intersections between chemistry and biology. While Good uses toxins to close ion channels, he is opening doors of possibility as to where a chemistry degree may lead.