Was it Mother Nature’s idea of improvisation?

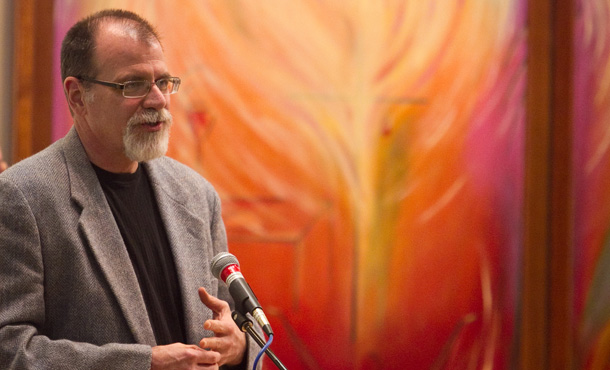

Participants in the Anabaptist Communicator’s annual conference sat around tables in Martin Chapel at Eastern Mennonite Seminary, mesmerized by actor-playwright Ted Swartz’s reflections on what he believes makes a “good Mennonite actor,” while outside, snow began to cover the EMU campus.

It was Oct. 28, too early for frozen precipitation in the Shenandoah Valley, which was yet to have a killing frost.

Some persons departed for home after the evening program, as the forecast was snow continuing through midday Saturday – which it did, leaving about four inches of wet snow that brought down tree branches and created power outages.

But, the unforeseen weather change seemed an appropriate backdrop for conference attendees, many of whom regularly face unexpected situations, even crises, in their communications work.

“Anabaptism in a Visual Age” was the theme explored in the two-day meeting of some 65 writers, public relations practitioners, graphic artists, photographers or in other administrative roles, the majority in church-related agencies and organizations. Eastern Mennonite University hosted the gathering.

Swartz, of Ted and Company TheaterWorks based in Harrisonburg, reflected on his development as an actor, which started with sketches presented at a Franconia Mennonite Conference youth retreat in Pennsylvania in 1987 with an accomplice he had only met several days earlier, Lee Eshleman. That inauspicious beginning evolved into a 20-year creative partnership as “Ted & Lee,” as the acting duo often combined askew humor and fresh insight in interpreting biblical narratives.

“Theater is a marvelous metaphor for faith and perhaps the best metaphor for how relationships should happen . . . Much of what makes a human relationship real I learned while pretending to be other people,” Swartz told the group. “An actor is on a search for meaning, feeling, a way to express the longing for a life greater than oneself.

“A good actor is one who is actively present in the moment, to care more deeply, on more about that moment than anything else.”

At the root of good acting, Swartz maintained, is “listening – it’s where you start. Are you really listening to the other actors onstage? If a play isn’t effective, there’s a good chance it’s lack of listening between the actors.”

The third prerequisite, he said, is “empathy, the ability to put oneself in the shoes, the clothes, the pain of another person,” Swartz said. “Without empathy, an actor cannot find the heart and soul of a character.

“The very act of crawling inside a character is the same act of embracing the other, seeing the eyes of the other, loving your enemy, “Swartz declared. “The very tenants of Anabaptist theology include taking the words of Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount to be the root of a reconciling gospel.

“When these three things happen onstage, it is just about the best feeling in the world,” the actor-playwright said. “It is a moment of transcendence, a deeply spiritual and mystical connection . . . Religious people call it ‘grace.’”

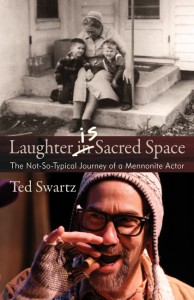

Swartz illustrated his points with sketches using his homeless character Zeus as well as a scene with EMU staffer Heidi Muller from his favorite theatrical work from college days, “The Lion in Winter.” He shared excerpts from his autobiographical work in progress, “Laughter as Sacred Space: The Not-So-Typical Journey of a Mennonite Actor.” The book, in three parts, is expected to be released the spring of 2012 by Herald Press.

Jerry Holsopple, professor of digital and communication arts at EMU and an award-winning artist and videographer, gave the keynote address on the conference theme. Using numerous art pieces, photographs and advertisements to illustrate his talk, Holsopple asked, “What visuals might best represent the Anabaptist-Mennonite way of communicating the biblical message?”

He showed the “Martyrs Mirror” etching of Dutch Anabaptist Dirk Willems turning around and rescuing his pursuer who had fallen through the ice, only to be tortured and executed for his faith.

“Mennonites tend to be people of the Word who worship the invisible God,” Holsopple said. “So can visuals help us in our journey in becoming more like Jesus?”

He shared his experience of teaching and studying during the 2009-10 school year as a Fulbright scholar at LCC International University in Lithuania, working with a Russian orthodox priest, Father Vladimir, in creating and painting religious icons.

“We all have icons in our lives,” Holsopple said. “It’s important not to wind up thinking that they have special powers and wind up worshipping them. “Our task, as Christians and as Anabaptist communicators, is to witness to the incarnational – the church as a physical and spiritual reality – the transformational – entering into what is happening around us; and the communal – creating space for dialog and changing ways that we see the larger world, other people and even ourselves.”

The conference included break-out sessions on topics ranging from branding messages for “the quiet in the land” (Christian Perritt), “art for social change” (Cyndi Gusler), “seeking shalom through a photographer’s lens (Howard Zehr) to “Anabaptist online engagement” (Brian Gumm). There were off-site visits to organizations with Anabaptist-Mennonite roots and guided affinity small group meetings on marketing, web and social media, graphic design and running a one-person shop.

The group viewed a new MennoMedia documentary, “Waging Peace: Muslim and Christian Alternatives,” then interacted with its producer, Burton Buller. The film is being aired on ABC affiliate televisions across the country.

As the conference ended Saturday noon, Oct. 29, so did the snowfall, and participants departed with fresh resolve to communicate their stories through Anabaptist eyes of faith.