Rite or Ritual

Divine - Sacred - God - Spirit

With our words we sew a suit for it

but it always bursts the seams

no regard for blush or shame, it seems

so it's fitting that this thing unnamed won't stay cinched

in the western clothes we've carefully stitched

Toothy temple bracelet tiers,

Jama Mosjid's twisted spires

ghat-descending funeral biers

and haunting red … Continue Reading ››

Montage of India

Through Post-neomodern Art

-Yelisey Shapovalov

I present to you the best of India through the art form that we millenials connect with most: selfies. My efforts began with the aspirations of sharing my adventures with my parents who are largely responsible for my being here; however, it turned out that they weren't … Continue Reading ››

India: Mussoorie, elevation 6,580 feet

Mussoorie Impressions

Mussoorie has carried with it more anticipation than any other stop on this trip for me. Although I enjoyed our racing around Rajasthan for two weeks, my mind and body were exhausted and looking forward to resting in one place for some time. As we boarded our third and final overnight train ride, I … Continue Reading ››

India: Rajasthan to Mussoorie

Dawn in Mandawa

Location: Roof of a Haveli in Mandawa, Rajasthan, India. 6:15 am.

The sound of music drifts through the brisk March air towards me from some unknown source. The city seems still and sleepy. Occasionally, I catch the moo of a cow and the chirp of a bird. Audible all around me is the sound of … Continue Reading ››

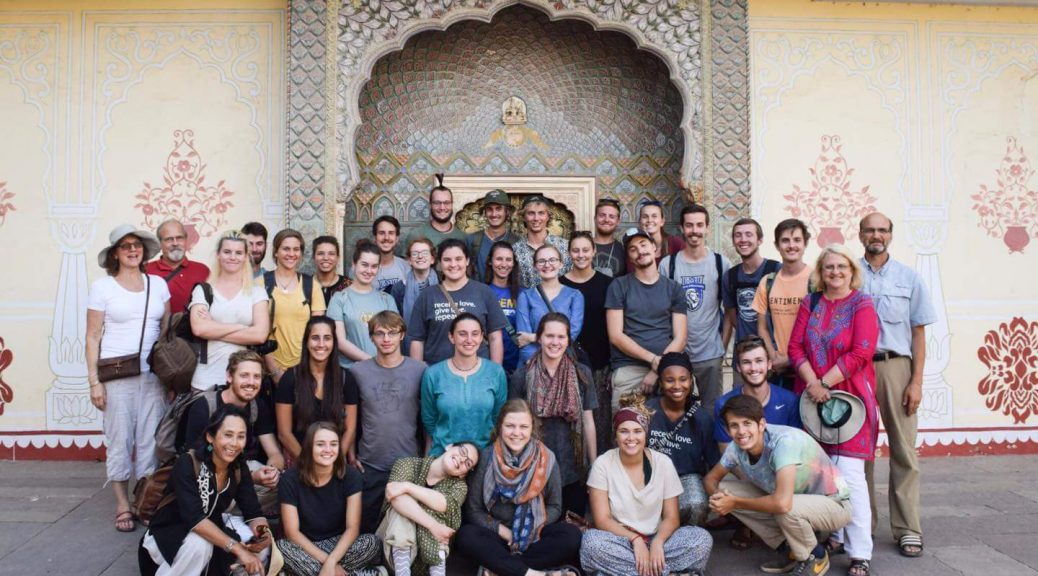

India: Rajasthan, Part II

El Classico, or A Day in Jaipur

An account of perhaps the most comically representative full-day experience of our entire trip. It all began with a man wearing a straw hat and a winning smile who stepped onto our bus that morning and invaded our lives forever. "Goodmorningmynameis[incomprehensible]butyoucancallmeJiJi––" he said breathlessly. "It's a good thing you … Continue Reading ››

Rajasthan Overview

After our stay at the Sarang Center in southern India, followed by our spring break week, we traveled back to Delhi before heading into northwest India – into the state of Rajasthan. Rajasthan, in Hindi, means "land of kings" and is the ancient home of a collection of forts, palaces, fancy tombs, and Silk Road … Continue Reading ››

Kerala & Sarang Center

A day in the life at the Sarang Center, second person POV:

6:15 am: First alarm

6:20: Second alarm

6:22: Get out of bed, throw Kalari clothes on

6:31: Take Rickshaw to Kalari

6:47: Arrive, lather oil on body, go through bowing routine

7:01: Smile and grimace after Guru-ji starts class with “Three laps!, one more, one more!”

8:30: leave class a … Continue Reading ››

India: Beauty, Colonization and Wrestling with Enough

Goa Reflection

The state of Goa is located in western India with its coastline stretching along the Arabian Sea. Its history, like much of India’s history, involves European colonization. The Portuguese set their eyes on Goa when realizing its valuable placement geographically as a port for spice trading along the Arabian Sea. In the late 1500’s … Continue Reading ››

India: Kolkata, Varanasi and Bodhgaya

We were told that Kolkata was an 18 hour train ride from New Delhi. The train ended up being 5 hours late and taking 30 hours to reach our destination. One of the "four rules of India" is "anytime after sometime," and we were truly experiencing this rule!

I cannot, however, say this experience … Continue Reading ››

Delhi Reflections

We landed in the capital city, Delhi, at around 1 a.m. local time on Monday morning. Half-awake and disoriented, we scrabbled to find our checked bags, hopped onto a bus, and arrived at a hostel just after 5 a.m. This put us at around 30 hours of traveling from when we left … Continue Reading ››