In 2016, Dr. Kathy Evans was interviewed for an article about restorative justice in education in The Atlantic.

Her message was simple: the implementation of an RJE program needs to be holistic, focused on transforming the school climate and culture, and also sustainable. It isn’t a quick and easy process that can be implemented after a one-day training, she said.

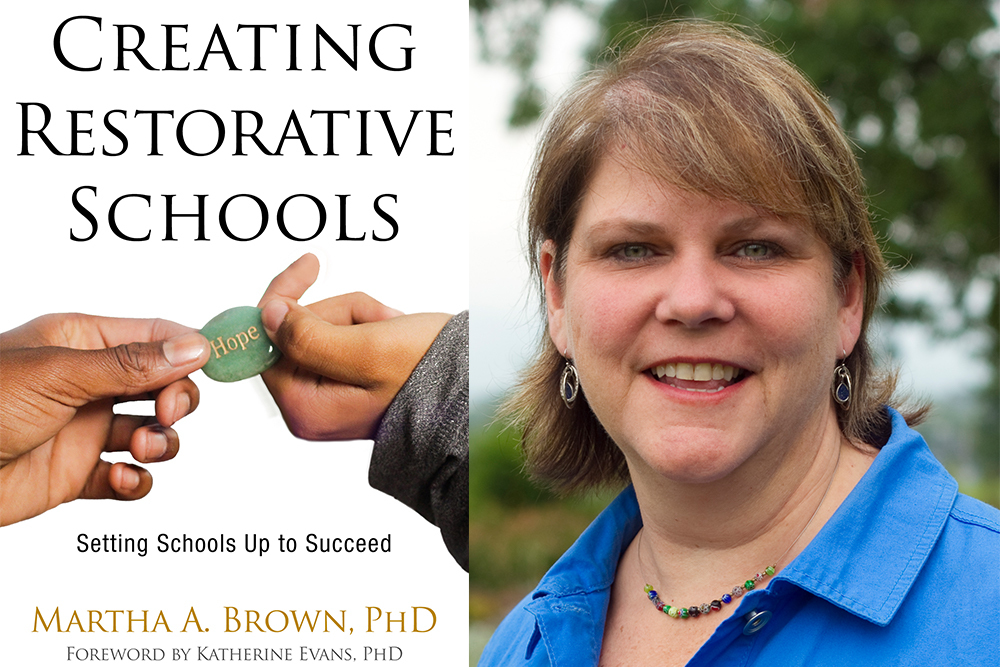

A new book “Creating Restorative Schools: Setting Schools Up to Succeed,” (Living Justice Press, 2018) by Dr. Martha A. Brown, helps illuminate that process and provides guidance for those looking to build and sustain restorative cultures in their schools. Evans provided the foreword.

One critic called the book “a must-read for anyone truly interested in an honest and practical approach to becoming a restorative school.”

The book features research conducted at two middle schools in Oakland, California, with different student populations and resources. Both schools were about three years into their implementation, challenged by the journey but committed to the vision of restorative culture. With the help of insights offered by students, teachers, staff and administrators, Brown shares a holistic picture of each schools’ relational ecologies and threats to program fidelity, consistency and continuity.

Living Justice Press, founded in 2002, is a nonprofit organization that publishes books on restorative justice, peacemaking, social justice and community healing.

Evans’ foreword is published here by permission from the author and Living Justice Press.

***

One of the great joys of my work as an education professor at Eastern Mennonite University (EMU) is collaborating with teachers and school administrators, counselors, students, and other school staff about restorative justice in education (RJE). In addition to sharing some of my knowledge about RJE, I have learned so much from the amazing educators and students I have been able to interact with. Much of that collaboration has been with local school districts in the Shenandoah Valley, including the Harrisonburg City Public Schools here in Harrisonburg, Virginia, where EMU is located. In addition to the current cohorts of educators who are enrolled in the graduate program in RJE at EMU, there are many other educators and community members working together to facilitate more restorative justice school practices in the area. It’s exciting to see the momentum growing and the commitment, not simply to implementing a program, but to building a culture. It is this type of culture shift that we are advocating for in Harrisonburg and it is the type of culture shift that Martha promotes in this book.

When Dorothy Vaandering and I wrote The Little Book of Restorative Justice in Education, we intended it as a framework, a compass pointing toward the principles, values, and foundations of RJE. At the end of the book, we called for restorative justice practitioners to work together to share ideas about what works and what doesn’t work in their schools and communities and for educational researchers to provide more data that supports and informs the applications of RJE. Educators in Harrisonburg, Minneapolis, Houston, Denver—and countless other places—are enacting these restorative principles in creative and powerful ways. Martha’s book adds to the growing body of research by documenting the applications of RJE in two middle schools in Oakland, California.

In her first chapter, Martha defines RJE as a “whole-school approach that prioritizes relationships, builds community, creates just and equitable learning environments…. [R]estorative schools support struggling students, teach peaceful conflict resolution, and repair relationships after a harm has occurred.”

In The Little Book of Restorative Justice in Education, Dorothy and I define RJE as “facilitating learning communities that nurture the capacity of people to engage with one another and their environment in a manner that supports and respects the inherent dignity and worth of all” (p. 8). According to both of these definitions, RJE is a holistic and comprehensive approach, impacting the way we interact at the individual, organizational, and community levels. It must impact more than simply the way we do school discipline; it has to impact the way we do school, including how we speak to students in the hallways, the way we engage with parents and caregivers, and the way we design our curriculum and our pedagogy. When RJE is implemented solely as a way to address students’ “misbehavior,” we miss opportunities to address the underlying causes of those behaviors; often those causes are rooted in relational issues, such as disengagement, mistrust, cultural barriers, implicit biases, microaggressions, lack of safety, and a host of other issues that impede effective learning. A holistic approach to RJE, as Martha describes in this book, seeks to address those underlying causes.

When RJE is put forth as an alternative to discipline, schools might actually experience a reduction in suspensions and expulsions. Without the cultural shift, however, we might simply be masking underlying issues that may still result in disproportional rates of discipline, increased frustration on the part of faculty who feel like nothing is being done to address misbehavior, continued lack of achievement, and a general lack of safety for everyone. Unfortunately, we have seen this too often in schools that received grant funding to implement a program while failing to do the hard work of creating a more restorative environment.

Conversely, when RJE is introduced as a shift in culture, we address the underlying issues that hinder learning; we focus on meeting students’ emotional and social needs, not simply their academic needs—realizing that they are all intertwined; and we challenge injustice and inequities that often are causing toxic and unproductive learning environments. This shift not only addresses discipline challenges, but also promotes effective learning opportunities for all students. Consistent with this holistic approach, Martha’s research identified four related themes: trust, having a voice, relational culture, and a commitment to social justice.

At its core, RJE is about relationships that are characterized by respect, dignity, and mutual concern. There’s an acknowledgment that we are all interconnected and that what happens to each of us impacts all of us. Driven by values, RJE is an ethos, not simply a set of practices or processes, but rather a way of being that guides those practices and processes. Effective educators know this; when relationships in the classroom and school are healthy, learning is facilitated. For example, attachment theory has stressed the importance of children and youth having significant adults in their lives; RJE practices build in opportunities to foster those types of healthy attachments by working with students to resolve challenging behaviors rather than relying on punitive measures that ultimately interfere with healthy relationships.

Working with students, rather than doing things to them or for them, promotes social engagement rather than social control. This ethos doesn’t just show up when we are addressing student behavior, but can impact our pedagogy as well. For example, Erich Sneller is a chemistry teacher at Harrisonburg High School and a participant in the RJE graduate certificate program at EMU. As we were discussing the impact of social engagement and social control, Erich talked about how in his chemistry labs, having students simply follow a set of instructions for completing the lab can easily become social control, but involving them as part of the problem-solving process related to the lab promotes social engagement. Students aren’t simply passive recipients but are actively engaged as chemists; this not only promotes their learning, but also builds positive interactions with Erich around chemistry.

One of the greatest contributions of Martha’s book, in my opinion, is in the way she establishes a more direct connection between the principles and practices of RJE and the important research on social and emotional learning (SEL). For those in the RJE community, Circle processes have consistently demonstrated the potential for assisting students and educators in developing social and emotional competencies such as self-awareness, social awareness, self-regulation, empathy, decision making, and problem solving. Many schools are already committed to promoting social and emotional competencies, so the links between RJE and SEL are important places for building on what is already happening. For example, Christy Norment is a school counselor at Harrisonburg High School and a participant in the EMU RJE graduate program. She facilitates Circle processes as a way of collectively solving classroom challenges. When teachers and students come together, with the help of a well-equipped facilitator, to resolve issues in the classroom, not only are they building a shared responsibility for the learning environment, but they are also creating spaces where students learn important problem-solving skills.

Relational ecologies are a primary aspect of RJE, but simply being relational is insufficient without concurrently committing to address injustice and inequity. Restorative justice must be about justice—and no less so in educational contexts. We can no longer talk about achievement gaps without acknowledging, along with Gloria Ladson Billings and many other critical educators, that there are instead opportunity gaps. As we pursue restorative justice in education, we have to talk about educational justice. This means responding to historical harms that have primarily impacted people of color, those with severe financial inequities, members of the LGBTQIA+ community, students with disabilities, and other marginalized youth. RJE that is holistic beckons us to ongoing professional development in antiracist pedagogy, culturally relevant teaching, and inclusive education. It calls us to examine issues of power and privilege, implicit bias, and microaggressions that create unsafe educational spaces for both students and teachers. Holistic RJE requires that silenced perspectives are lifted up and that students and teachers are invited into decisions about school policy and practice. Martha’s research reminds us that a commitment to social justice must be part of the work of RJE.

Finally, Martha’s work in this book reminds us that implementing RJE practices requires more than a few add-ons; the work of building more restorative school cultures requires a paradigm shift—and those don’t happen overnight. RJE is not a quick fix. It is about changing school culture or, as we say in The Little Book, changing the way we do things around here. Change is messy, nonlinear, and unpredictable. There are things we can do to facilitate it, but with all our best intentions, sometimes it shows up or doesn’t in the most random of ways.

Based on her research, Martha offers some suggestions for how we might facilitate this type of cultural shift. Martha and the educators she worked with in Oakland understand the current context of public schooling and the challenges that schools face; yes, there are barriers, but in the face of these barriers, schools are continuing to move toward more restorative educational cultures.

Martha emphasizes that having support from district administration is crucial; however, initiatives cannot be mandated from above. Without sufficient buy-in from members of the learning community, mandated initiatives not only violate the principles of RJE—setting it up for ultimate failure—but can also violate trust and exacerbate ineffective relationships in a building.

For example, Harrisonburg City School District has over fifty different languages represented and is home to students from more than forty different countries. Many students each year are newcomers and many have arrived as refugees. Dr. Scott Kizner, superintendent, and April Howard, director of Student Services, are committed to improving the learning environments for this diverse mix of students in the district and realize that in order to build a restorative school culture for all of those students, there needs to be a variety of supports. Dual language programs have been designed, after-school programs are in place, and the district is committed to building more trauma-informed education. District administrators are supportive of RJE and work with other staff and building administrators to find innovative ways to build a more restorative culture without mandating more programming for those educators who haven’t yet been convinced of the efficacy of RJE. The result is perhaps a slower cultural shift, but one that has stronger foundations and greater buy-in.

We need more institutional support for RJE; yes, funding is tight for educational institutions, but as Martha notes, we have a choice about how we will invest the monies we do have. Investing monies in capacity building creates a more sustainable shift in RJE; providing ongoing professional development for educators within the building, rather than bringing in experts from outside, is not only economically prudent but also ensures that the RJE efforts are led by those who understand the context in which those efforts are being made. What works in one space may not work in another and what might be essential in one school might matter less in another.

One of the ways we are doing that in Harrisonburg is by preparing educators to be RJE leaders in their buildings through a partnership between Harrisonburg City Schools and EMU. EMU offers a graduate certificate in RJE that ensures a depth of knowledge in both theory and practice. Educators, including teachers, administrators, school counselors, family-school liaisons, and behavior specialists, take classes together that are designed to facilitate their ability to lead the efforts to build more restorative school cultures. At Harrisonburg High School, a critical mass of educators has completed the certificate program and they are now doing their own professional development within their school. We believe this to be a more sustainable model for implementing RJE than models where outsiders are coming in and doing trainings for a day, without attending to the unique needs of the school and without attending to the depth of knowledge needed to implement RJE with fidelity to the values and principles of RJE. It also honors the existing expertise of those educators, building on what they know and bring to the learning experience.

In conclusion, decades of zero tolerance policies have proven ineffective at addressing the learning needs of students and creating safe and effective learning communities. Refusing to see that the cost of educating our young people is less than the cost of incarcerating them, we have often persisted on resorting to the same old punitive measures that have accomplished nothing and, in many cases, have exacerbated school failure. We must repeal these policies and replace them with policies that have been proven to actually work to make schools safer. Martha’s research supports the effectiveness of RJE and its potential to do that. She reminds us that we all pay for the costs of zero tolerance policies and their impact on our youth and children. Money spent on expensive policing could be more wisely spent meeting the needs of our youth and children, equipping them with the social and emotional skills, as well as academic proficiencies, needed to succeed and contribute to our world.

Henry Giroux, in his critique of zero tolerance policies, argues that “rather than attempting to work with youth and make an investment in their psychological, economic, and social well-being,” these laws and policies are “designed not only to keep youth off the streets, but to make it easier to criminalize their behavior.”1 Restorative justice in education actually reverses that trend and seeks to make an investment in the well-being of not only our students, but all those involved in our educational systems. As Martha points out, while zero tolerance policies offer a quick response with no sustainable solutions to the underlying problems, RJE asks us to invest now in our youth with a promise of relational dividends later.

We still need more research on the efficacy of RJE in various contexts, but Martha’s book offers great insight into the work happening in two Oakland schools. Consistent with other research, the centrality of relationships and the emphasis on social justice ring strong through her writing. I am grateful for this book and hope that it will provide a strong grounding for educators seeking to advocate for and implement RJE in their classrooms, schools, and districts.