“Our country was birthed in a polarized cradle,” David Brubaker writes in the introduction to When the Center Does Not Hold (Fortress Press, 2019). First, patriots and loyalists faced off leading up to the Revolutionary War. The American Civil War followed within the century. Then came the Vietnam War and the civil rights movement of the late 1960s.

“I believe the turmoil of the 1960s and early 1970s set the stage for our current era of polarization. Those of us in the baby-boom generation were shaped in the turmoil of the 1960s,” Brubaker writes. “And it is members of the baby-boom generation who now occupy the majority of leadership roles in business, education, health care, and government.”

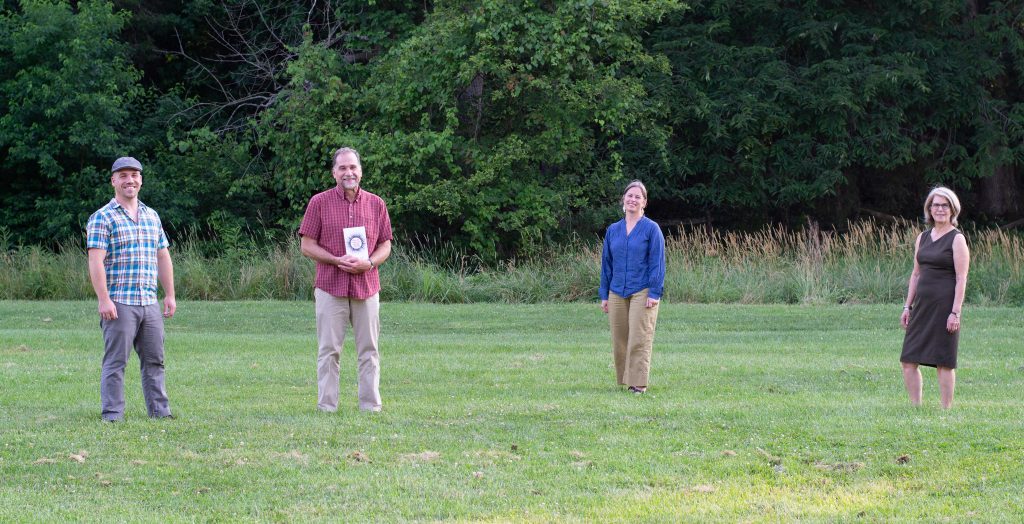

When the Center Does Not Hold is like a guidebook grounded in sociology, offering mentorship for leaders who find themselves in polarized environments, such as the entire United States in the current era. Brubaker, dean of social sciences and professions at Eastern Mennonite University (EMU), co-authored the book with contributors Everett Brubaker ‘15, his son; Teresa Haase, former director of EMU’s MA in counseling program and current director of the Center for Grief and Healing at Hospice of the Piedmont; and Carolyn Yoder, the founding director of EMU’s Strategies for Trauma Awareness and Resilience program (STAR) and author of Little Book of Trauma Healing (SkyHorse Publishing, 2020)

Their target audience is faith-based leaders in congregations, educational settings, communities, and other organizations. But David Brubaker noted that secular, for-profit, and governmental leaders will also find the concepts applicable.

It was also important to him that the book be accessible for a wide audience – so each chapter opens with a story illustrating its concepts: like that about a Pennsylvania coal miner who supports Trump, proponents for and against the 2003 invasion of Iraq, and even EMU’s own listening process about hiring faculty in same-sex relationships.

When the Center Does Not Hold goes beyond mere analysis of polarization. It calls for a special kind of leadership in response: leaders who are clear about where they stand, but also interested in the “experiences and beliefs of others in the systems they lead,” David Brubaker writes. “This is because the antidote to polarization is not conflict avoidance but conflict engagement.”

Each of the four authors brought insight from their own careers. David Brubaker said his interest in polarized systems began in 1991, when he encountered a high intensity conflict case in a congregation. An allegation of sexual misconduct came out against the lead minister, whose response further fractured the congregation.

“None of our traditional tools of structuring dialogue were effective, and we soon realized that we were in new territory,” he recalled.

Everett Brubaker, now the resident services and communications coordinator for the Harrisonburg Redevelopment and Housing Authority, has a background in working on environmental issues including climate change. He completed a master’s degree in environmental communication and advocacy from James Madison University in 2019. His chapter focuses on effective communication.

As he watched debates over the veracity of climate change, “I recognized we would need additional skills to address what were ultimately challenges in communication, not necessarily a lack of knowledge or science,” he said.

Haase brings counseling expertise to the table, with a specialty in grief and loss. Her chapter opens with a story about her grandmother, whose “courage and fierce compassion have always inspired me to lead from a heart-centered place with determination and perseverance,” said Haase. “In my experience as a leader, I have found resilience and vulnerability to be key factors for weathering adversity and polarization.”

Yoder’s background is also in counseling, specializing in individual and group trauma. In her chapter, “Trauma, Polarization, and Connection,” she draws on two key concepts to understand polarization.

“What traumas have we experienced and what traumas have they experienced that bring us both to this way of seeing? This helps foster compassion and humanize each other,” says Yoder. And “understanding the neuroscience – the physical effects – on our brain and bodies of feeling safe or feeling threatened in a situation or in talking about a situation. This helps us understand the individual and group actions, reactions, beliefs and behaviors associated with each.”

The book’s final chapter opens with an analysis of Jesus’s own tactics in both assembling a diverse group of disciples in a polarized world, and instructing them to love their enemies while resisting their “dehumanizing behavior and the oppressive systems that supported such behavior.”

“When we are able to name and resist the systems that violate human dignity while affirming the dignity of those trapped in such systems, we are helping ‘to protest and neutralize’ the onerous practices of our day,” David Brubaker writes. “And when we form loving communities that reflect the broad diversity of our society, we are demonstrating that relationships can flourish even in an age of polarization.”