Hawaiian coffee growers used to have a leg up on much of the rest of the world: The number one insect pest for the industry – coffee berry borers – hadn’t yet shown up on the islands.

But that changed in the last decade, and this summer Eastern Mennonite University Professor Matthew Siderhurst and two students aimed to beat even “cuppers” – trained coffee tasters – at identifying the borers’ impact on Hawaiian coffee.

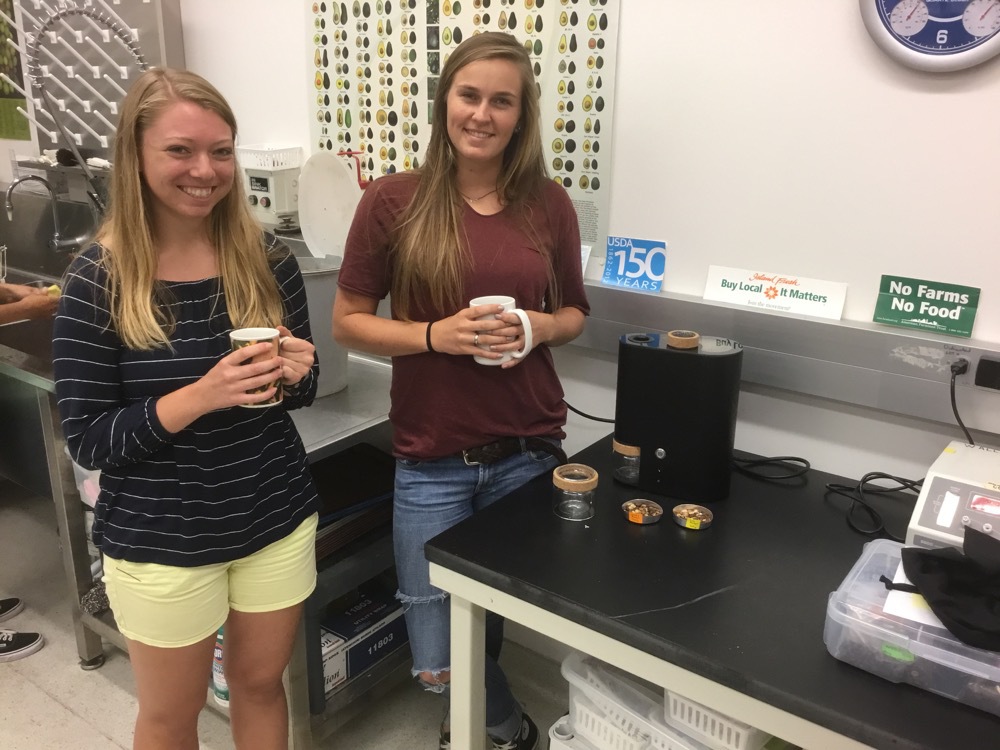

Hannah Walker – she graduated in May with majors in biology and environmental sustainability – and Leah Lapp – a biochemistry major who will graduate in two years – were among the five undergraduate students at EMU who were awarded Glenn Kauffman and Roman Miller Research Awards of $2,500 each to support their research this summer.

The awards, named for professors emeriti Glenn Kauffman (chemistry) and Roman Miller (biology), are sponsored by donors to the Daniel B. Suter Endowment Fund and the CT Assist Grant Fund. The financial support can be used for student summer research wages, research supplies, and travel and fees to present ongoing or past work at a scientific meeting.

In Hawaii, Walker and Lapp each used a different device to detect the coffee borer damage.

“We’re very interested in the quality control side of this,” Siderhurst said.

The instruments

Walker’s tool was a gas chromatograph mass spectrometer, a six-feet long, $200,000 lab bench behemoth they referred to as “the GC mass spec.”

The instrument enabled them “to see what volatiles are coming off damaged roasted coffee beans,” to decipher the chemical fallout of coffee berry borers’ destructive presence, she said. The GC mass spec took a lot of adjustment – “a lot of trial and error,” Siderhurst said – but that “messing around” with equipment aspect of research was “very eye-opening, really cool,” said Walker.

“Thank goodness this man” – she points to Siderhurst – “knows instruments pretty well.”

Read a Smithsonian magazine article about Professor Matt Siderhurst’s research.

Lapp helped to establish standard operating procedures for new techniques using an electronic nose, a much less costly device that’s small enough to carry. Once trained, the “e-nose” will be able – “theoretically,” said Lapp – to indicate the degree of damage in masses of beans, say to test bags of coffee on a production line.

But first it had some learning to do, through random “sniffing” of vials filled with coffee beans, each vial containing a different percentage of borer damage.

“We spent a lot of time sorting coffee beans,” said Lapp. “It’s really important that you sort them correctly, because that will change all your results.”

Lab blend

Walker and Leah weren’t only thinking coffee beans, though. The U.S. Department of Agriculture lab where the trio worked is also home to more than 50 other researchers and staff. For another project the duo helped maintain a fruit-piercing moth colony, harvesting leaves three times a week from Wiliwili trees for caterpillar feed and pupation locations.

And once a week they checked a trapline for the subject of another Siderhurst study about longhorn beetles.

It was, Walker said, “a nice variety of being in the lab using different instruments and being out in the field and having to ‘talk story’ [a Hawaiian term for ‘chat’] with people who let us use their property for trapping.”

They also got to know the area, Walker said, which was “cool,” except for the nauseating vog – volcanic fog – from the erupting Kīlauea. The mountain was downwind from the lab, but not always from everywhere else they needed to go.

‘No wrong answers’

Lapp called this summer “an amazing experience” because she learned what it’s like to work not just in a classroom laboratory where “the professor’s leading you towards a certain conclusion,” but in a setting where there are “no wrong answers,” she said.

“It allowed for creativity, and we brainstormed a lot,” she said. “We were always trying to figure out, ‘Okay, what’s next? This failed; why did it fail?’ Or, ‘This worked; how can we use what we learned from this to further our research?’”

Siderhurst said that for researchers like Walker and Lapp, the work is only partially finished at the end of the summer. Once back at EMU, they’ll work together to write papers or create posters and presentations about their research.

“It’s fun,” he said.

It must be, because this was Walker’s second summer on the GC mass spec project, and she said she could see such lab research being part of her career or ongoing studies.

In the meantime, she said, “We were kept on our toes.”