Finding and catching salamanders might look like something Eastern Mennonite University senior Cerrie Mendoza would have done as a science-loving child, but in reality, amphibian hide-and-seek was just one aspect of her internship this summer.

Mendoza, a biology major from El Paso, Texas, is taking part in a collaboration pilot project between the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History (NMNH), the U. S. Geological Survey, Eastern Mennonite University (EMU) and James Madison University (JMU) to gather genetic samples from certain North American species of salamanders that were first collected and described 50 years ago. The project is funded by the Smithsonian’s Global Genome Initiative.

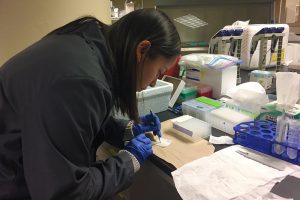

In addition to finding and catching salamanders, Mendoza is learning research practices like DNA sequencing and publishing DNA barcodes, said Dr. Daniel Mulcahy, a NMNH molecular laboratory technician and one of Mendoza’s supervisors. “This immerses Cerrie into the inner workings of many professionals in the museum, each conducting a variety of different methods to accomplish their jobs.”

Exceptional experience

The placement is also giving Mendoza firsthand experience of the complexities of scientific research beyond what many interns undertake.

“She has to function as the project leader,” said one of herinternship supervisors, JMU professor William Flint. “She has to actually think about and plan how to execute all of the steps. Many times, students at Cerrie’s level or age are simply functioning as lab or field techs which requires very little leadership or planning. For this project, however, Cerrie cannot just show up to work and wait to be told what to do. She has to figure all that out and then make it happen.”

It’s not the first time Mendoza has figured something out and made it happen. She is attending EMU because she wanted to “find my faith again” and searched online for “small Christian universities.” After visiting, she said, “I fell absolutely in love with the campus, Harrisonburg, the Valley and Virginia. I wouldn’t want to go anywhere else.”

In addition to many fun, new experiences (with healthy doses of “Oops,” “What’d I just do?” and “Was I supposed to do that?” moments), Cerrie has also been reaffirmed in her belief that science — her favorite subject since grade school — is a vital pursuit: “I love learning how nature and animals connect and respond to our environment and how they impact our world and how we impact theirs. We live in a cycled world where many things use one another in order to survive, and having that information for everyone to see is important.”

Sequencing DNA

In her internship, Mendoza is adding data to the descriptions of certain salamander species found in Virginia.

When a new species — of salamander, for example — is found and described by scientists, it becomes the “gold standard” against which all future comparisons of that species are made. In recent years scientists have begun including DNA evidence in the descriptions of these “type specimens,” said Dr. Rayna Bell, another of Mendoza’s mentors this summer and a research zoologist and curator of amphibians and reptiles in the NMNH Department of Vertebrate Zoology.

In the past, though, DNA information was not known and so wasn’t included in type specimen descriptions. Mendoza and fellow intern Greg Steffensen of JMU are working to collect genetic samples from some of those same species of salamanders — in the exact locations where the original type specimens are from — to add to records.

Mendoza has contributed to the project by researching species in journal articles, planning species collection trips to efficiently include multiple sites, packing supplies and choosing campsites. She has helped to sequence the DNA from the collected samples and enter the sequences into the Global Biodiversity Barcode Network, and to curate those new specimens in the NMNH National Collections.

This kind of science can be thrilling for novice scientists, Mulcahy says — and he describes moments that could sound exciting even for the unscientifically minded who don’t understand the technical terminology: running “PCR results on an agarose gel,” seeing “bands of DNA (exposed under ultraviolet light) for the first time,” and “realizing they just amplified their first pieces of DNA.”

And that’s not all, he says — because then they get “those sequence results back” with “the actual DNA copy of nucleotides, As, Ts, Gs, and Cs, all in a unique order for that individual. Then it’s exciting when they blast that sequence and find out how close it matches the representative specimens already in GenBank, 97%? 99%? Or is it not the species they thought it was?”

“Basically, this summer was a crash course in how to be a modern field biologist,” Bell said of Mendoza’s experiences, and added that Mendoza’s internship is giving her much more than time with salamanders.

“Regardless of whether Cerrie ends up working on Virginia salamander taxonomy in her future,” she said, “she now knows what it takes to organize a field expedition (including what to do when things don’t go exactly as planned), some important research techniques like DNA sequencing and the importance of taking detailed field notes, and maybe most importantly, she now has a whole team of mentors to support her in whatever she decides to do next!”

We are very proud of our Biologist/Environmentalist. Love You Baby!!