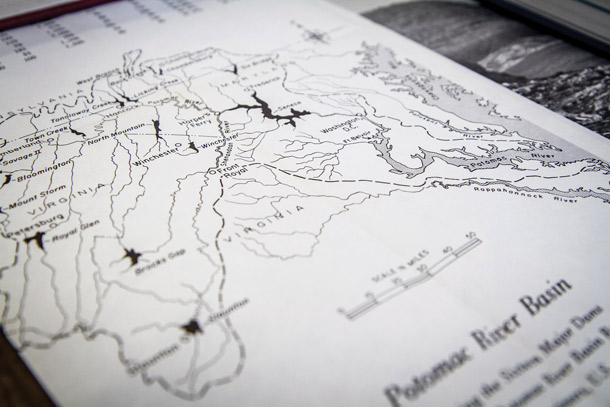

In 1963, the United State Army Corps of Engineers published plans to build 16 large dams along the Potomac River and its tributaries, including one at Brocks Gap on the North Fork of the Shenandoah River, about 15 miles north of Harrisonburg. The Army Corps’ goals were noble enough: to spare Washington D.C. from the destructive flooding that had periodically drowned the National Mall, secure the city’s water supply for decades to come, and create 16 new lakes’ worth of recreational opportunity for the American public.

Of course, there were some pesky details to all of this. The 150-foot dam proposed at Brocks Gap would have buried the community of Fulks Run beneath 122,000 acre-feet of water, displacing more than 300 families and inundating, among other things, nearly 4,000 acres of productive farmland, a brand-new elementary school and at least 17 places of businesses.

It was, obviously, an upsetting plan to the people of Fulks Run, as was it upsetting to Ernest Gehman, then a professor of German at Eastern Mennonite College and a minister in the Virginia Mennonite Conference. Gehman had come to know and love Fulks Run through the preaching circuit that took him to congregations in the area, and the fact that two Mennonite churches – Hebron and Bethel – were to disappear beneath the many waters of the Brocks Gap Reservoir truly raised his ire. (In all, seven or eight churches in Fulks Run would have been flooded.)

“He knew a lot of people who would have been affected by the flooding of the valley,” said James Metzler ’62, Gehman’s son-in-law, who is married to Rachel Gehman Metzler ’54. “He was concerned for the livelihoods, the disruption of congregations, as I recall.”

Gehman made his feelings on the matter plain in a May 1963 letter he wrote to Harrisonburg’s Daily News-Record (using language remarkably similar to certain strains of contemporary political discourse): “It is the sort of trampling on human rights that one might expect to find in atheistic Russia, but hardly in our so-called free and so-called Christian America.”

The situation in Fulks Run felt dire, recalls Garnett Turner, the owner of a then-threatened country store famous for its sugar-cured Turner hams. Turner recalls the officer leading the Army Corps’ plans as being “right emphatic that it was going to happen” – the security of the nation’s capital was said to be at stake.

Gehman knew the best way to block the Army Corps’ plan was to suggest an alternative; his counter-proposal involved the construction of smaller dams along the entire length of the Shenandoah River. Built every five to 10 miles within the channel of the river (and thus known as “channel dams”), these were to have kept the water no higher than flood stage, essentially turning the Shenandoah into a series of long, narrow lakes.

The idea was inspired by channel dams that Gehman had seen in the late ’40s in Germany while completing his doctorate at the University of Heidelberg, and a decade later during a year he spent teaching in Austria under the Fulbright exchange program. The Neckar River, which flows past Heidelberg, was a particular inspiration.

Gehman argued that the channel dams would serve the Army Corps’ water supply and flood control goals without destroying the community behind Brocks Gap. He also played up the economic development angle, as the addition of locks at each dam could open the Shenandoah River to commercial navigation.

Like most conservative Mennonites of his era, Gehman frowned on participation in politics and never voted in his life, according to his son John Gehman ’59. That didn’t stop him, though, from diving into the bureaucratic and political fray surrounding the Army Corps’ scheme. (The eldest of Gehman’s five children, and only other one still living, is Huldah Gehman Claude ‘54.)

“He was bold,” recalls John, who was in medical school in Richmond while his father took on the Army Corps of Engineers. “He didn’t hesitate to speak up about his thoughts and feelings.”

In September 1963, Gehman went to Washington to present a rationale for his channel dam proposal at a public hearing held by the Army’s Board of Engineers for Rivers and Harbors. (Also there that day was Garnett Turner and nearly 200 others who’d come from Fulks Run in five chartered Greyhound buses to make their displeasure known.)

He began writing to the newspapers, local officials, state legislators and Virginia’s Congressional delegation. Responses, ranging from tepid to fairly enthusiastic, came back from Virginia’s two senators at the time – Harry F. Byrd Sr. and Willis Robertson – as well as Governor Albertis Harrison and West Virginia Governor William Barron. Gehman’s greatest ally in Washington, though, soon became Rep. John O. Marsh of Virginia’s 7th District.

In one of the many letters the two exchanged over a several-year period, Marsh wrote: “The time you have given to this problem is a most valuable contribution to the public interest.”

John Gehman, now a general practice physician who lives in Crewe, Va., remembers that his father “just kept drumming away at it,” despite a growing sense of frustration when the channel dam plan seemed to be going nowhere.

Gehman also struck up correspondence with the German Embassy in Washington, and in the spring of 1964, organized a meeting between high-ranking American officials and a German engineer named Gerhard Krause who was an expert on Germany’s channel dams.

With the help of Krause and other contacts in Germany, Gehman then compiled an 18-page brochure that examined the German channel dams in considerable detail and fleshed out his plans for similar dams on the Shenandoah River. In May 1965, the Broadway-Timberville Chamber of Commerce funded the printing of 2,000 copies, which Gehman and his allies began distributing widely. Later that summer, Marsh wrote to request more copies, as the brochure was “attracting considerable interest” in Washington DC. In June, it reached the hands of Lady Bird Johnson – the First Lady of the United States, who wrote in a letter to the Broadway-Timberville Chamber of Commerce:

Professor Gehman’s study of channel dams in the Potomac tributaries interests me very much, and I am sending it to Secretary [of the Interior Stewart] Udall so that he and his professional staff can give it full and immediate consideration in their plans.

In August, another 1,000 copies of the brochure came off the press, and by year’s end, Gehman had spoken about his idea to around two dozen civic groups in the Valley.

(The plan wasn’t without its drawbacks. A state game official wrote that construction of the channel dams would destroy the Shenandoah’s smallmouth bass fishery, considered one of the finest in the country. The Izaak Walton League, a private wildlife and habitat conservation organization, formally opposed the Gehman plan for the same reason.)

By mid-decade, though, significant resistance was mounting to the Army Corps’ original plan for Brocks Gap, which seems to have been quietly pigeonholed. The historical record (and the Army Corps’ own archives) is remarkably silent on the specifics of how, exactly, this transpired, and the details escape the memory even of people like Garnett Turner who fought to save his own home and business. The Army Corps plan was there, until suddenly it wasn’t.

Regardless, once plans for the Brocks Gap dam dissolved, Gehman also shelved his channel dam plan that had consumed an enormous amount of his time and energy of over a several-year period.

In 1973, Gehman officially retired from EMU, after teaching for 47 years. Over the next decade or so, he continued to teach a few German classes until his health began to fail him, and in the summer of 1988, he died at the age of 86.

The Turner Store is still in the family and still sells its fine Virginia hams. The Fulks Run Elementary School recently celebrated its 50th anniversary. Fertile farmland still covers the valley west of Brocks Gap and surrounds the still-intact Hebron Mennonite Church. And Runions Creek still runs past Bethel Mennonite Church before reaching the North Fork of the Shenandoah, which then flows unencumbered through Brocks Gap and down the Valley towards Washington D.C., as it did since before Ernest Gehman and the Army Corps of Engineers devised competing plans for its future.

— Andrew Jenner ’04