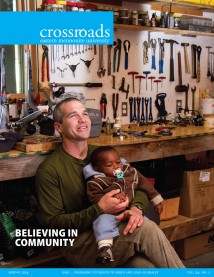

Among the Collins Center’s trained forensic interviewers are three EMU graduates – family advocate Rhoda Miller ’03, Ana Arias ’99, a counselor and associate director of the Collins Center, and director Angie Strite ’02. (Photo by Jon Styer)

The way things used to work here went something like this: A child might mention something suggesting sexual abuse to a parent or a teacher. The child might be asked to talk about it with their guidance counselor, and then a social worker. A police officer would come ask questions about what happened. An investigator – yet another strange adult – might come, ask the same questions all over again. The prosecutor would conduct yet another interview as he or she prepared the case and, perhaps, the young victim would be called to the witness stand, face to face with their abuser, to testify.

Sometimes this worked, but the process had its drawbacks. Chief among these was potential re-victimization of children who were repeatedly asked to recount traumatic stories as they were shuffled through a system that wasn’t developed with their developmental and therapeutic needs in mind.

In 2008, Harrisonburg’s Collins Center – a sexual abuse and assault prevention and response organization in the community – created its Child Advocacy Center (CAC) to better support victims and their families during the investigation and prosecution of child sexual abuse. One of the CAC’s important techniques is the forensic interview, conducted by a trained interviewer who helps a child talk about their sexual abuse. Police, prosecutors and child protective workers monitor the interviews by video in another room; they can suggest questions through an earpiece worn by the forensic interviewer.

The result is a streamlined process that helps prosecutors build their cases but emphasizes the well-being of the victim throughout. (Because recordings of the forensic interviews aren’t admissible as evidence at trial, victims are sometimes still called to testify in court; when this happens, the CAC also provides specialized preparation beforehand.)

Among the Collins Center’s trained forensic interviewers are three EMU graduates – CAC director Angie Strite ’02, family advocate Rhoda Miller ’03, and Ana Arias ’99, a counselor and associate director of the Collins Center. Conducting these interviews with children, they say, can mean going through our community’s darkest corners. The larger statistical picture is exceedingly grim: estimates vary considerably, but up to 25% of all children – and up to one in three girls – may be sexually abused at some point. Assuming that holds true locally, well over 6,000 children younger than 18 in Harrisonburg and Rockingham County are victims of sexual abuse, meaning the 152 cases handled by the CAC last year hardly scratch the surface.

Focusing on the specifics of a particular case is one way to keep from losing hope, says Miller; Strite adds that working on the center’s prevention programs provides some uplift (all three have responsibilities at the center beyond conducting forensic interviews). Then there’s the simple resilience they encounter in children. In their line of work, they see a lot of awful stuff, says Arias. But they “also see the miracles.”

Today, the CAC works with a multi-disciplinary team, including law enforcement, prosecutors, social services and medical providers, to keep tabs on every child sexual abuse case that’s moving through local courts.

Clark Ritchie, a deputy commonwealth’s attorney who prosecutes cases of child sexual assault and abuse, notes that the center’s long-term treatment programs for child victims provide an important service to the community.

“Being a victim doesn’t stop after the case is over,” says Ritchie. “The Collins Center is one of the few entities that exists in this community that will be with the victim long after I’m out of the picture.”

— Andrew Jenner ’04