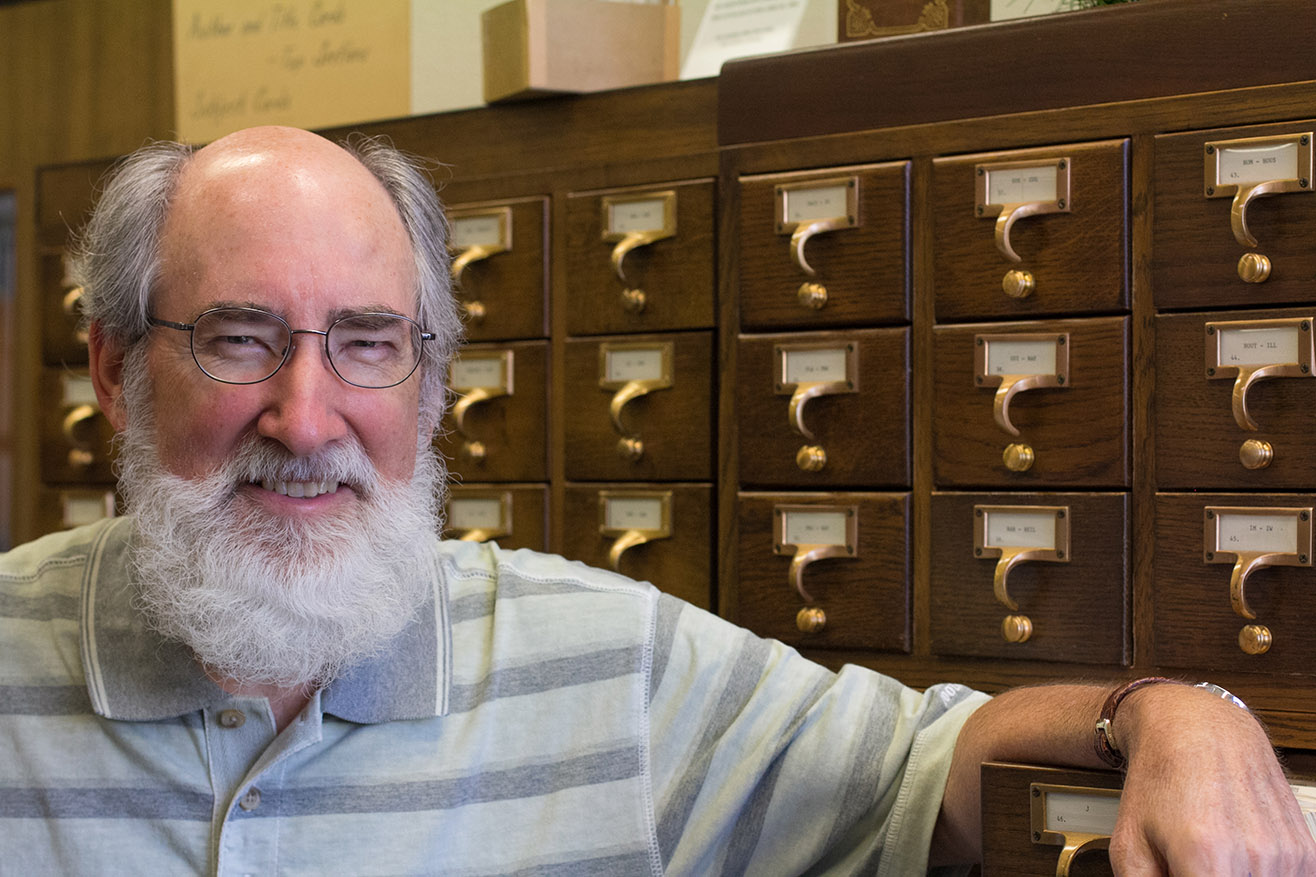

Centennial historian Donald B. Kraybill ’67 reflects on six years of research for his book Eastern Mennonite University: A Century of Countercultural Education to be released by Penn State University Press in September 2017.

How does the length of time spent on this project compare to your many other published works?

Each project has its own quirks. I’ve completed some short books in two or three months. Others have taken ten years. And several others I’ve never finished! The EMU history was especially complicated. I faced over 100 years of time and an archive brimming with thousands of rich original sources. To hazard a wild guess, I probably only looked at 10 percent of the available primary sources.

What were the most rewarding parts of the research and writing?

Discovering three distinctive educational paradigms that reflected the three stages of the institution: school, college and university. To share in that discovery, you’ll have to read the book!

Can you share about the research and writing process?

In most of my projects, I’ve been fortunate to have a team of two or three skilled associates. This time I had the university’s support – in particular Provost Fred Kniss and the expertise of archivist Nate Yoder and special collections librarian Simone Horst, as well as my editorial associate Cynthia Nolt. A major challenge was how to organize thousands of copies of documents into a little research archive at my home. When it comes to writing, my rule of thumb is make a mess and clean it up at least 10 times.

I’m a better editor than a writer, but I’m not a copy editor. The editing is what makes the writing sing. I’ve rewritten many of the sentences in this book at least a half dozen times – attending to alliteration, clarity and a graceful flow. Even so, I’m still plagued with prolixity.

What were the challenges of this project?

One challenge involved the multiple expectations of my diverse readers: current faculty and staff, older alumni, recent alumni, donors, development and marketing staff, historians and other scholars. I even hope a few current students will read it! Each sector of that multifaceted audience holds different expectations. How could I craft a narrative grounded in primary sources with some analytical depth that was readable, engaging and interesting for such a mixed audience?

The second challenge was interpreting the last 25 years. It’s hazardous to interpret recent history. I felt much freer to analyze the conflicts and failures of the players in the first 75 years. Most were no longer living and their issues were often less pertinent in the 21st century. I had to treat the last quarter century more gently – with little analysis and more description. Most of the recent players are still living and many remain employed by EMU. I am quite vulnerable as a writer because they know more about the issues and conflicts than I do.

A third challenge was reconciling the diverse views and suggestions of 15 readers of an early draft and three copyeditors. I was fortunate to have their generous advice and perspectives. In the end, I have to assume responsibility for the final text.

What surprised you about EMU’s history?

Four things come to mind. I didn’t realize that the school had failed twice in Virginia (Newport News and Alexandria) before it was founded at Harrisonburg.

Second, I was amazed that Virginia Mennonite Conference had no control over the school until 1924.

Third, the toxic relationship between Goshen College and EMU until the mid-20th century astonished me. EMU was founded as a conservative alternative to Goshen College and the ideological strife between the two institutions was intense in the first three decades.

Finally, although I graduated in 1967, I had not known that EMU was the first private college to accept African-American students (1948) in the state of Virginia and one of the early ones in the entire South.

Who were the early heroes of the school?

In my mind, there were three. Beginning in 1912, bishop George R. Brunk I – a self-educated, brilliant theologian – provided the most articulate and persuasive arguments for why Mennonites in the eastern states needed to establish a conservative school.

Second, after two aborted starts, Mennonite bishop L.J. Heatwole almost single-handedly resuscitated plans for an eastern school at Harrisonburg.

Finally, A. D. Wenger, the second president from 1922-35, provided the managerial skills and financial acumen to stabilize the fledgling school and to keep it afloat during the depression. His short booklet ‘Who Should Educate Our Children?’ made a convincing case for why EMU mattered to skeptics in the church.

What did you learn about history in general?

We tend to assume that there is one true story of the past. This is the myth of the single narrative. Histories however are socially constructed. I could have crafted several different narratives. A Century of Countercultural Education is my particular story. Other writers and other scholars might have crafted quite different narratives about EMU’s past.

What would you do differently if you could begin this particular project again?

I conducted about 40 interviews early in the process. I would conduct them later after becoming more familiar with the primary sources. Interviews are very time-consuming. I would likely do fewer of them.

What was your biggest temptation?

James Wert ’68 reminded me, ‘History is messy and historians shouldn’t try to clean it up too much.’ Historians are apt to flatten, smooth out, amplify issues, skip over other ones, and tidy up the past. We also are tempted to patch fragments of the past together into a single linear narrative to make sense of the past. History is not always linear. Historical events have multiple causes. I struggled to keep fidelity with the messy past while still fitting parts of it into a satisfying narrative.

What’s unique about this institutional history?

This is a social history. I selected particular topics – gender, race, dancing, instrumental music, biblical interpretation among many others – which I found interesting from a sociological perspective. I also explored conflict. We often express our most deeply held values and beliefs more explicitly during conflict than in the routine flow of life.

What are you most pleased about?

I visited Hubert Pellman, emeritus professor of English, in the fall of 2016 a few weeks before his 98th birthday. He had written a history of EMU’s first 50 years (1917-67). A few weeks before my visit, he sent word through Professor Marti Eades asking if he could see an advance copy of the book. He told her that he ‘would wait for the Lord to call him home until he could see a sneak preview of the book.’

Not wanting to hinder divine providence, I sent him several draft chapters. When I met him, he praised the chapters as ‘elegant,’ and repeatedly told me, ‘Now I can die a happy man.’ We had a wonderful hour-long visit. His eyes sparkled, his mind was sharp, and as always his spirit was gracious. It was an unforgettable sublime hour. [Hubert Pellman passed away March 20, 2017.]

When you finish such a long project, what do you do to celebrate and to mark the achievement?

The first day after transmitting the manuscript to the press feels odd. Suddenly there is silence. No need to think about or worry about the project after several years of being obsessed by it. I savored roasted salmon over a large spinach salad in a quiet corner of a restaurant to enjoy the sudden lull and read the Chronicle of Higher Education, one of my favorite periodicals.

Did you “meet” any people in EMU’s history that you would have enjoyed learning more about?

I would enjoy speaking with Ada M. Zimmerman, who became the first dean of women in 1940. She was a progressive thinker and articulate writer. Hubert Pellman described her as the seed of women’s emancipation at EMU.

Is the motto “Thy Word is Truth” still relevant for EMU?

In the course of the research, I discovered a fascinating essay by C.K. Lehman, academic dean (1923-56) when the motto was adopted in 1928. He points out the multiple layers of interpretation for the phrase. In the context of John’s Gospel, Jesus is the Word and the Truth that sets us free. I think the motto remains pertinent today for keeping EMU centered on Jesus and the perennial search for truth in the midst of a world of lies, fake news and propaganda.

What is your vision for EMU’s next century?

I hope it continues to promote a resilient, robust and engaging Anabaptist-Mennonite identity of peacebuilding.