Ernest G. Gehman vaults in front of the Ad Building in the 1920s. Truman H. Brunk (left) and Jacob Shenk hold the bar.

In January 1920, students scrubbed windows and floors and moved into the new facility at the base of the hill, walking in shoe-deep mud carrying items from the old hotel. The new building eventually would be known as the “Administration – or ‘Ad’ – Building.” It was a strictly functional, stucco-covered “cracker box” rising four stories on a bare hillside, initially landscaped with a single cherry tree.

There – for the next 25 years, with an annex attached to the south side in 1926 and one to the north in 1942 – students studied, visited library shelves and tables, ate meals, slept, worshipped in chapel, met with professors and staff, and received visitors.

Jim Bishop ’67 who has studied and worked at EMU almost every year since 1963, has no lingering affection for the old Administration building, calling it “hideous looking.” It reminded him of the Alamo fort in Western movies. Yet there were those who loved it, as this account will touch upon later.

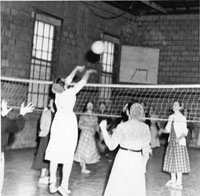

A gathering inside the exercise hall of Eastern Mennonite.

Until the 1940s, there were few facilities apart from the Ad Building. Students and faculty built a barn-looking wooden “exercise hall” in 1926. A twister felled it four years later. Its replacement in 1930 was a cinder block building about 2/3 the size of a regular gym, with no space for spectators.

“It was like playing basketball in an oval because people were crowded into the corners, trying to watch,” retired physics professor John L. Horst Jr. ’60 recalled recently. Early users called it “X-Hall”; later some referred to it as “Kuhl Hall,” meaning it was “cool” – actually downright cold – much of the year in the absence of a heating system. The building stands to this day, having seen successive generations discover new uses for it, including theater and arts studio. Today it is used for storage and is a candidate for demolition, given the roughness of its construction, rustiness of its roof, and cracked single-paned windows. “It wasn’t built to be lasting,” says physical plant director Eldon Kurtz ’76.

Volleyball inside the exercise hall of Eastern Mennonite.

Faculty members in the first decades needed to be exceptionally flexible and self-sacrificial. M.T. Brackbill wrote this in his diary on April 20, 1920:

I think I am either honored or imposed upon with offices, some of which are as follows:

1. Instructor in science, math and English.

2. Registrar.

3. Hall manager; S.S. Chorister.

4. President Athletic Association.

5. Class Professor.

Besides I give exercise to the boys in calisthenics every evening, serve on various committees, [and] take part often in special music numbers.

This, for a salary that would have been double if he were working almost anywhere else. To supplement his school pay, Brackbill sometimes worked as a carpenter or helped farmers at harvest time. Such moonlighting “did keep the teachers out of ivory towers,” Pellman noted dryly.

The view of Massanutten Mountain from the grounds of Eastern Mennonite is almost the same today as it was in 1920, but today’s grounds are lushly landscaped compared to the early years. Ernest G. Gehman, a college student and teaching assistant in 1920, organized the Young Men’s Improvement Association to clean up lumber and other debris, make terraces and do general grooming of the grounds. The front campus was a cornfield. A truck patch provided vegetables for the school kitchen.

The response to President Smith’s fund appeals was disappointing, but diligent requests by a half-dozen volunteer “solicitors” did reduce the debt to $10,000 by the spring of 1923. Smith wrote wistfully in a personal letter of needing “a Carnegie Mennonite or some such capitalist who would agree to raise the balance because of what has already been raised… We need money, MONEY, money, MONEY….”

There were few large sums from individual donors. Most support came from many persons who gave small amounts. “The constituency found it hard to believe that an educational institution could not be made to support itself by tuition and other student income,” noted Pellman. EMU’s current vice president for advancement, Kirk Shisler ’81, says it is still not widely understood that paying full tuition covers only a fraction of the cost of educating a college student, not just here but in any college, public or private.

President Smith resigned in 1922 over a matter that would have caused him no trouble in later years. At a time when instrumental music was officially banned from Mennonite churches and frowned upon as a general rule – it was viewed as leading to worldly pursuits, rather than spiritual ones – Smith’s home had a piano, which his oldest daughter played.

Out of step with his church conference on the piano and a couple of other matters, Smith was replaced as president by evangelist A.D. Wenger (supported by his wife, who stopped playing the pump organ). Wenger made it a priority to whittle down the school’s debt load through active fundraising, with himself being a leading donor. But necessary capital improvements kept the debt in the $10,000 range. When the Ad Building was enlarged by a south annex in 1925, the debt rose to $25,000 ($297,000 in today’s dollars), despite the sale of 30 acres to a local farmer.

The original Ad Building, before the 1926 annex was built with mostly volunteer labor.

In 1924, D. Ralph Hostetter accepted a $600 a year loss in salary – the equivalent of a $7,000 pay cut today – to shift from a Pennsylvania high school to teach biology and chemistry at EMS. Hostetter came with a masters degree in education from Harvard, which caused him to be viewed with suspicion by some board members.

Hostetter lobbied for better care of the grounds. “In our Park,” he wrote, “…we find fish, eggshells, cans and rubbish dumped on the grounds, also pig pens built there. These things are very unsightly and obnoxious. We recommend that no more land be sold, but it be developed for the purposes stated above (a piece of ground…where students may get a touch of the wild; where they may study birds, flowers, trees, etc., as found in nature)… [T]ransplant and replant trees, plant wild flowers, preserve bird and wild life and keep grounds mowed in decent shape.”

Ernest G. Gehman, who left EMS long enough to earn a masters degree in 1927, played multiple roles at EMS. He taught German and was the English-language czar, zealously correcting spelling, punctuation and grammar. But he also was known for “faithfully soliciting between school terms for students and funds.” (To this day, his widow Margaret Martin Gehman ’42 is a generous contributor to EMU.)

In 1927, President Wenger issued a report in which he approvingly noted that “each year for six years except ONE we have met all our running expenses from the income of the school.” He pointed out: “It is only when we make improvements that we are in need of charity.” In other words, tuition covered paying the teachers, but not much else – certainly not improved or new facilities.

Wenger kept tight reins on the college’s expenditures – so tight that students paid two cents a term for every watt of light they used above 40. Two students who wanted to study an extra hour per week beyond study hall periods were charged for the additional light they used.

The summer before the stock market crash in 1929, six faculty members went out to beat the bushes for money and students. Wenger observed, “Nobody [on the faculty] enjoys solicitation,” yet they disciplined themselves into doing it. The school needed to expand its curricula to qualify for state accreditation, but the Depression put EMS into acute financial straits. The faculty did everything they could to save the school. They offered to take a 10 percent pay cut, three women taught for the salary of two, one professor offered to take whatever load he was given. By 1933-34, the school was down by 25 students in total enrollment.

Life went on despite the hard times: G. Irvin Lehman ’35 received a reprimand for writing an English essay in which he defended radio broadcasting and predicted that EMS would one day have its own station.

In an effort to help students through the hard times in 1933-34, Gehman, along with President Wenger and local Mennonite leader Erasmus C. Shank, established a toy-manufacturing company that put 40 students to work on a part-time basis. In less than two years, more than 200,000 toys made from scrap aluminum were sold in stores such as Woolworth and Kresge. One of these workers was Frances Suter ’34, whose earnings kept her in college despite crop failure on the family farm. She, in turn, helped her brother, Daniel B. Suter, through school. Later in life, after marriage to Frank Harman, Frances became a major donor to her alma mater. (Gehman retired from Eastern Mennonite in 1971 after 47 years of service.)

In the summer of 1935, President Wenger reported that attendance was up about 20 over the previous year, but financial aid was needed for the “hundreds of our young people who would be glad to get a Christian education if they knew how to finance it.” If Wenger were on the financial aid committee of EMU today, he would find that his statement remains true and that donors are still sought for the University Fund, from which financial aid is drawn.

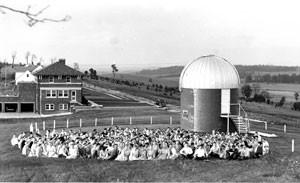

In the early 1930s, M.T. Brackbill – a dynamic teacher who recited poetry, quoted literature, loved music, and taught art, in addition to knowing science – inspired students to start the Astral Society to study the heavens. Their first star watches occurred on the roof of the Ad Building.

The 1938 graduating class honored Brackbill – and the way he filled them with awe of God’s universe – by raising funds for building a small observatory on the Hill.

Vesper Heights Observatory was – and is – a short red brick silo capped by a steel dome which can be opened from the inside by a strong person wielding a crank the size of a crowbar. Unfortunately, says Horst, the locally made dome never opened and pivoted easily, as was necessary to permit use of the telescope housed under the dome. So another use was found for the dome.

In 1945, it was turned into the “sky” against which scenes of stars, planets, and other celestial objects were projected by light emanating from a small machine called a Spitz A, pictured here in an article on the class of 1959. In other words, the observatory became a tiny planetarium. (From 1955 to 1988 the dome also was opened at times for star gazing.)

“Spitz A” was invented for small planetariums by a friend of Brackbill’s, Armand N. Spitz, who sought to spread planetary study from large venues in big cities to the grassroots. Eastern Mennonite got the first Spitz A produced, bearing serial number 1. Princeton got the second, with serial number 2. From the late 1940s up to the 1980s, Spitz machines were installed in hundreds of high schools, colleges, and small museums. This is one area of technology where EMS/EMC led the way.

Brackbill retired in 1956. After the Suter Science Center opened in 1968, planetary studies shifted to bigger and better space there. In 2004, the year before he retired, astronomy professor Joseph Mast put a new 10-inch, digital $3,000 telescope into the observatory – the first telescope there since 1988. Should this telescope be moved somewhere else? (Weighing 70 pounds, it is compact enough to be moved by car.)

Trees have grown so tall to the east and west of the observatory, they obscure the lower skies in those directions. And the observatory is no longer in a rural location away from city lights. Should the observatory itself be moved to a darker, higher location? Should a new, easily opened dome be bought for the old silo? Some universities, including James Madison, have been putting telescopes on the roofs of their science buildings. Should an observation post be built into the expanded science center EMU hopes to build?

“For amateur astronomers and undergraduate students, you probably wouldn’t build an observatory today,” said one astronomy buff recently. “You would use a portable telescope with a tripod, and you would take it where you could get the best view.”

So…is it time to dismantle the observatory-planetarium on the Hill? Ask this of someone who was one of Brackbill’s “Astralites” – a title conferred only on those who could name 90 stars and the constellations – and he or she will look pained. “I have such wonderful memories tied up with that observatory,” says Dr. Kenton K. Brubaker, member of the class of 1954 and retired EMU science professor. “I would hate to see it go.”