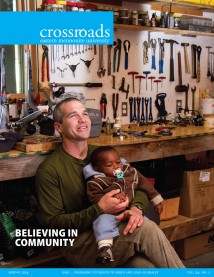

Gemeinschaft started in a home previously owned by Barry Hart, MDiv ’79, professor of trauma, conflict and identity studies at EMU’s Center for Justice and Peacebuilding. (Photo by Jon Styer)

The twisting corridors and ad-hoc floor plan suggest a history of repeated additions and expansions to the Gemeinschaft Home, which once again is bursting at the seams.

In late 2013, a closet-building campaign was launched to ensure the growing number of residents of the home – which helps former inmates find work and provides various therapeutic services as they transition to life outside prison – had a place for personal storage, says executive director Sharon Glick.

On Mount Clinton Pike, just over the hill from EMU, the Gemeinschaft Home receives funding for 25 residents through the Virginia Department of Corrections’ Community Residential Program. Some residents who complete that 90-day, state-funded program remain for a longer period, paying their own way by working jobs they’ve landed through Gemeinschaft, often in the local construction, manufacturing or poultry industries.

About 40 residents are now crammed into the home, with a long list waiting for a spot as soon as one opens. In the fall of 2013, Gemeinschaft (“Guh-MINE-shaft,” the German word for “community”) was booking places up to eight months in advance.

“We constantly get calls from people who want to return,” adds program director Kirk Saunders, who oversees the therapeutic programs all residents are required to participate in – and to which, according to several people familiar with the home, the program owes much of its success.

In terms of hard statistics, a study in the early 2000s by the Department of Corrections and James Madison University found that ex-inmates who completed a stay at Gemeinschaft were significantly less likely to be re-arrested, convicted or incarcerated than offenders who completed therapeutic pre-release programs in prison.1 Saunders conducted a less statistically rigorous assessment in 2012, when he reexamined the files of 85 residents, chosen at random, who had been discharged within the previous three to five years. Of this group, he says, only a half-dozen or so had ended up back in jail.

According to Lisa Kinney, a spokesperson for the department of corrections, programs like Gemeinschaft benefit the entire state by not releasing offenders into communities where they may be homeless, by reducing the likelihood that they’ll directly return to their pre-incarceration social environments, and by giving them a chance to establish some financial security as they transition back to normal life.

Before the often-added-to house had anything to do with corrections, or had been added to quite as much, it was home to a group of EMU students who lived there in an intentional community called Gemeinschaft. One of the student residents from that era was Barry Hart, MDiv ’79, now a professor of trauma, conflict and identity studies at EMU’s Center for Justice and Peacebuilding. After finishing his seminary degree, Hart bought the house with two others with the intention of founding an intentional Christian community that welcomed ex-offenders.

Hart and the other co-founders had all been involved in prison ministry, and at first, opened their home to three or four people they’d gotten to know through that work on a completely informal basis. While everyone worked various jobs during the day, residents made it a goal to share a meal together every night.

“It was about equality and respect and honoring each other’s dignity,” says Hart.

Six years into the experiment, it was becoming increasingly difficult to make ends meet. Although local probation officers had caught on to the operation, and were sending residents supported by state per-diems, Hart had become the only “core” member (i.e., non-transitioning ex-offender) of the house, making it hard to maintain any kind of stable community. After finding himself unable to recruit others to join him in the venture – due, at least in part, he thinks, to the intentional community ideal entering a cultural tailspin in the mid-’80s – Hart put the house and everything in it up for auction in 1985.

As the auctioneer stood on the front lawn selling off the furniture, Hart and a group of supporters, including long-time sociology professor Titus Bender ’57 and Lewis Strite gathered in a back room talking about the good run Gemeinschaft had had. Right then and there, Hart recalls, they were struck by a collective realization that it just couldn’t end. Maybe a group could buy the house, form a board, give a little more institutional structure, support and sustainability to the idea?

Strite, whose philanthropy eventually earned him a conference area named “Strite” at EMU, agreed to contribute a down payment and Hart dashed out to the front lawn to cut the auction short before the house itself was sold. The place was soon reborn as The Gemeinschaft Home, 501(c)3.2

There’ve been other ups and downs in the nearly 30 years since, but the trajectory of late has been strong. Saunders would be glad if they got funding for even more residents from the state, at which point they’d probably have to tack yet another wing onto the sprawling structure that’s become something few would have imagined when a group of EMU students living in the original house first began calling the place Gemeinschaft.

— Andrew Jenner ’04

1. One statistic from the study: 13.7% of ex-inmates who entered Gemeinschaft between July 2000 and June 2002 were recommitted to prison by 2004, compared to 23% of ex-inmates released over the same period who did not enter any kind of therapeutic program.

2. Current members of its board of directors with direct ties to EMU are James Good ’61, Ruth Stolzfus Jost ’71, Sam Showalter ’65, Harvey Yoder ’57 and Carl Stauffer ’85, MA ’02, assistant professor of justice and development studies.