The reason Hizkias Assefa has two law degrees, two master’s degrees, and one doctorate is not because he loves living buried in university libraries.

It’s because he had to leave his home country of Ethiopia when his friends and relatives were being killed or imprisoned during the Derg’s 13-year military dictatorship.

He got to the United States on a student visa in 1973 and kept plowing through a succession of degrees while his parents were telling him: “Stay out. Stay where you are, or you will be killed.”

Assefa was able to return safely to Ethiopia in the early 1990s. By then he was married to a U.S. citizen, with two daughters.

In hindsight, Assefa treasures the breadth and depth of his formal graduate studies – law, economics, public management, and international affairs. “The more I learned, the more it whet my appetite to learn more,” he told Peacebuilder magazine.

“I realized the benefit of this broad background when writing my dissertation. Every discipline gave me a different lens for looking at conflict and peace, and it was most useful to integrate them together and come up with a multi-disciplinary approach.”

Before coming to the United States, Assefa practiced law briefly in Ethiopia. “There was not a lot of integrity in the profession. It was competitive, and I felt like I was a hired hand for the elite. I felt co-opted into the system.”

Later in Chicago, when he again was part of a law firm, he felt the same discomfort. “The lack of integrity wasn’t as blatant as it had been in the Ethiopian judicial system – it wasn’t as crude – but it was there.” These experiences weren’t a waste – he believes studying and practicing law sharpened his analytical capacity and enriched his later work in the peace field.

Assefa turned to economics, earning a master’s degree in the field, in an attempt to understand poverty. He found economists have “fantastic ideas” – “great insights” – but offered little in terms of addressing poverty. If one tries to understand “economics without politics, it’s like clapping with one hand,” he says. “You need to understand politics to understand the role of power in economic systems.”

Outside of formal graduate programs, Assefa has delved deeply into psychology, philosophy and religion, subjects he needed to “put it all together.” As the “icing on the cake,” Assefa turned to studying peace and conflict transformation, plus practicing in the field, for 30 years now.*

“The kind of knowledge needed to be a peacemaker is not easy to define – I feel it more than I can talk about it. I think we have to start by reclaiming our humanity. Who are we as human beings? What is our place in the universe? What is life itself?” he asks.

“Human beings are not separate from everything in our environment. We cannot treat our environment as a group of objects to be used as we wish. We are part of an interdependent whole. If we can come to recognize this reality – that our survival, our well-being, derives from the healthiness of this interdependence – our attitude will change towards other humans, indeed towards all life and every aspect of living in this world.”

As Assefa gropes for words to describe the lack of awareness among humans about their place in the web of life, he explains that the English language limits his ability to articulate his feelings on this subject. “I am writing a book in Amharic now – though I stopped using it [his native language] 40 years ago – because it lets me touch on ideas that I can’t explain in English well. It lets me be less inhibited, less apologetic for exploring [in his book] the non-cognitive aspects of life and being that go beyond regular social science academic discourse.

“Some of what I want to say is beyond the intellect – in fact relying on the intellect alone can become a hindrance. It is part of the problem with discourse in the Global North: the main framework is intellectual, with very little room for the affective and spiritual.”

Assefa says there is wisdom in the perception of some indigenous elders that the so-called developed North tends to function as an immature child within the family of humankind, acting impulsively and without much self-reflection. “I hope the family will survive the growing-up stage of the child,” Assefa says wryly, adding that socio-economic and military practices of the so-called developed world underlie much suffering in the world today.

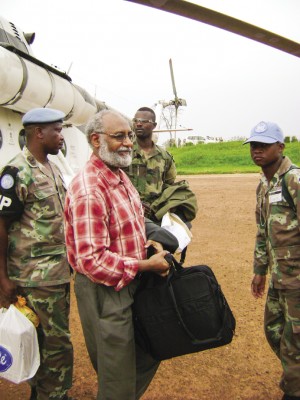

When Assefa feels tempted to succumb to despair, he calls to mind miraculous, heart-to-heart moments, like a time in 2006 when he was one of two with whom Joseph Kony agreed to meet in a remote area of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Kony, known to have used tens of thousands of children as soldiers and sex-slaves, had been indicted the previous year by the UN’s International Criminal Court for war crimes and crimes against humanity.

“After being lured into the bush, we were surrounded by armed people. I thought we were being kidnapped,” says Assefa. But when he finally met Kony face-to-face and spoke gently with him, Kony met Assefa’s eyes and said, “I never knew my father. Can I call you my father?” The question touched Assefa to his core – not that it diminished the enormity of the harm that Kony had set in motion for millions.

“I felt moved to see a flicker of humanity and vulnerability in this incredibly cruel and overtly invincible human being,” says Assefa. “It made me realize that compassion ought to be the starting point for peacework. The work of peacemaking is to nurture these little glimpses, however faint, and bring them out so that they can shine more and light up the darkness in our humanity.”

# # # #