EMU Archivist Simone Horst wrote this article for the Anabaptist Historians website.

“Anabaptist Historians: Bringing the Anabaptist Past into a Digital Century” is a collaborative blog by Anabaptist scholars, both those working from an Anabaptist identity and those studying Mennonites, Amish, Brethren, and other branches of the Anabaptist tradition. Its mission is to share cutting-edge scholarship with a broad readership, to foster relationships between scholars of Anabaptism, and to encourage debates on critical issues in contemporary Anabaptist faith and life.

We are living through very challenging times. 2020 thus far has been marked by uncertainty, upheaval, and loss of many kinds. For the first time in a long time, we are facing a collective hardship that requires us to make personal sacrifices for the good of society. Many have turned to history, studying events like the Spanish Flu and the Great Depression in an attempt to glean wisdom and find a path forward for our nation. At Eastern Mennonite University we can also look to the responses to these events in our own history—the Spanish Flu arrived just a year after the school opened its doors and a decade later the Great Depression tested the school just as it began to find its footing. I wrote earlier about the Spanish Flu at EMS, and today want to focus on the Great Depression. In each of these stories, we find examples of resilience that can inform our response today and give us hope for the times ahead.

October 29, 1929, better known as Black Tuesday, ushered in financial downfall all over the world and set the stage for the Great Depression. The still-young Eastern Mennonite School was not exempt from its impact. EMC historian Hubert Pellman writes in his book Eastern Mennonite College, 1917-1967 that “in the period 1929-34 the expansion of curriculums to qualify for and hold state accreditment and the decrease of enrollment and other straitening financial conditions caused by the depression made the problem of finances particularly acute.”1 But with community sacrifice, frugality, and ingenuity the school was able to survive and thrive.

Even before the Great Depression hit, faculty and staff were no strangers to low compensation, being paid only one half of what other faculty in the area made. But this financial problem would require even greater sacrifice—“on Sept. 11, 1931, the faculty heard that the school lacked the money to pay its employees.”2 The dedicated faculty and staff went above and beyond to make up the difference, offering to give up another ten percent from their already meager salaries. A select few were pressed into giving up even more–the three full-time women on the faculty, Sadie Hartzler, Ruth Hostetter, and Dorothy Kemrer, were chosen by the faculty to receive a two-thirds salary, because they were unmarried and it was determined that “those who are married should be the last to suffer.”3 (Unsurprisingly, all the married faculty were men.) Ruth Stolzfus Stauffer Hostetter said that the women, “knew through those early years that single women didn’t get the pay of married men. We recognized that it was happening. But we seldom talked about it.”4 Their reduced pay continued from 1931 until 1934, when their full salaries were reinstated. 5 Hostetter claimed that there was “comfort in numbers” since so many other Mennonite institutions and their workers were feeling the same crunch, and that she just “was thankful for an opportunity to serve in a professional setting.”6

The executive committee of EMS also thought of creative ways to reduce the number of faculty and staff without firing anyone. In addition to those working for severely reduced wages, some took on lighter course loads and others were encouraged to return to school to continue their education, with the hope that they could return once things improved. 7

The dedicated faculty and staff placed the needs of the school above their own to realize the school’s mission of distinctly Mennonite education and their sacrifices did not go unnoticed or without thanks. In the August 1931 Eastern Mennonite School Bulletin, Dean C.K. Lehman wrote a very affirmative report about the faculty of EMS, praising them for “laboring under handicaps,”8 but continuing to put forth their best work as educators. H.D. Weaver, business manager at the time, also gratefully noted the ten percent reduction in salary that the faculty took.9

Cost-cutting around campus was also necessary, and this was championed by President A.D. Wenger, who “taught and exemplified frugality.”10 Even before the Great Depression, Wenger was intent on penny pinching and keeping EMS to a strict budget. Pellman reports that “students paid two cents a term for every watt of light above forty,”11 that they were expected to study together in a study hall instead of their dorm rooms to conserve electricity, and that modern conveniences like telephones and adding machines were not brought to EMS until almost a decade after the school’s inception. In the years before the depression this budget-saving tactic was effective, with quite a few years under Wenger’s administration ending in the black. 12

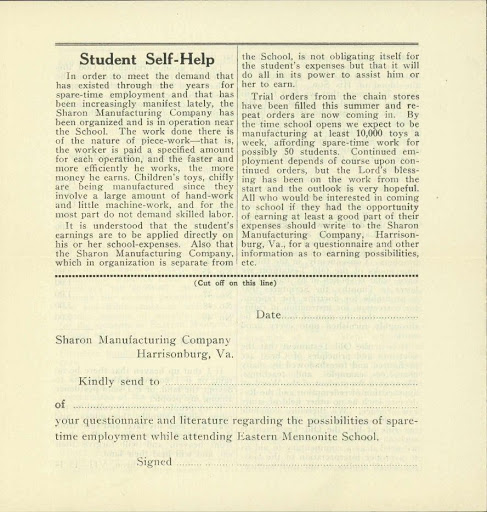

Wenger’s frugality was essential during the Great Depression and his ingenuity was just as integral to the school’s continuing survival. To help students afford tuition and make it feasible for them to continue attending EMS, he started the Sharon Manufacturing Company along with Ernest G. Gehman and E.C. Shank. They manufactured cast aluminum toys and operated out of a farm building on EMS’s campus. The company was the “only maker of cast aluminum toys in the United States,”13 and was quite successful in its heyday, selling to large department stores like Woolworths and Kresge’s. But the greater success that emerged from this business risk was the employment of up to forty EMS students which allowed many to afford tuition and continue attending. Ultimately, however, the company met its end in 1934 when it was shut down by the U.S. Government. 14

As evidenced by the size and scope of EMU today, Eastern Mennonite School survived the Great Depression and thrived in spite of it. Its financial setbacks were great at times, but it had loyal faculty, students, and constituents who were willing to work together in order to see the mission of EMS realized. The administration succeeded through their frugality, innovation, and shrewd decision-making that required sacrifice but respected the dignity of everyone in the community. As we continue to grapple with the challenges of our times, we can find inspiration and hope in the ingenuity, tenacity, and resilience of those who came before us.

- Hubert Pellman, Eastern Mennonite School, 1917-1967. (Harrisonburg: Eastern Mennonite College, 1967), 98.

- Ibid., 97.

- Ruth Krady Lehman, “How Three Women Helped Save the School” Eastern Mennonite College Bulletin 62, no. 2 (1983): 4.

- Ibid., 4.

- King, Mary Jane “Ruth Hostetter” Eastern Mennonite College Bulletin 62, no. 2 (1983): 5.

- Ruth Krady Lehman, “How Three Women Helped Save the School” Eastern Mennonite College Bulletin 62, no. 2 (1983): 4.

- King, Mary Jane “Ruth Hostetter” Eastern Mennonite College Bulletin 62, no. 2 (1983): 5.

- Hubert Pellman, Eastern Mennonite School, 1917-1967. (Harrisonburg: Eastern Mennonite College, 1967

- Chester K. Lehman, Eastern Mennonite School Bulletin vol. 10 no. 8 (August 1931): 3.

- H.D. Weaver, Eastern Mennonite School Bulletin vol. 10 no. 8 (August 1931): 4.

- Hubert Pellman, Eastern Mennonite School, 1917-1967. (Harrisonburg: Eastern Mennonite College, 1967), 104.

- Ibid., 104.

- Ibid., 104.

- Ibid., 104.

It does put things into perspective to read of other hard times.

Does anyone yet own one of those cars?

The Menno Simons Historical Library has a number of these cars still, and occasionally they come up on vintage toy websites. Only 200,000 were made and sold originally, so I understand that they are highly collectable!

-Simone Horst, Special Collections Librarian and Archivist

Here are a few human interest details from that era that I grew up hearing about.

My mother, Miriam Lehman Weaver and her sisters Esther and Dorothy (children of C.K. Lehman) told about their childhood memory of going “up to school” during the depression years to buy food at cost from the EMS kitchen storage room. My Aunt Dorothy remembers getting dried beef, cheese, dried beans, and raisins among other things. They would weigh their items on a scales and take everything to the kitchen where they wrote down what they had gotten on a board behind the door. One of the cooks would tally their order and accept their payment. Aunt Dorothy also remembers her father bringing home from the kitchen a huge box of cornflakes which they stored in the dry attic and ate from for weeks and weeks. Her memory is that the box was a three foot cube, but I suspect it looked larger to her as a child than it really was. She also remembers her father bringing home a fifty pound bag of sugar. Allowing faculty to buy staples at cost was one of the ways the school tried supplement their meager salaries.

When I talked to Aunt Dorothy today she commented that at least EMS continued to pay their faculty throughout the depression as opposed to Goshen College (where Dorothy now lives) who had to stop paying faculty salaries altogether for awhile.

In addition to the toy manufacturing mentioned in the article, most faculty members had to create an additional source of income. For my grandpa, it was raising chickens. If you walk down College Avenue where a number of faculty members lived, even today, you can see vestiges of chicken houses behind almost every house on the right side of the street from Mt. Clinton Pike to Shenandoah Street. Aunt Dorothy remembers washing the water fountains for the chicken house, a job she hated but that needed to be done. All the children had to help with that venture.

Unfortunately, almost all of the faculty children who experienced those years are now gone. I’m sure many good stories have disappeared with them.

I am the daughter of Emma Zimmerman Horst and am intrigued by the photo. I have never seen this unusual backdrop. I would have interest in buying a copy. My mother served during the depression in numerous capacities from nurse to dietitian, neither of which she had formal training. She was self taught and very resourceful.

Thanks for your interest and sharing more about your mother. I’ve emailed you directly to connect you with Simone Horst, who wrote the article and is also our university archivist.

–Lauren Jefferson, Director of Communications