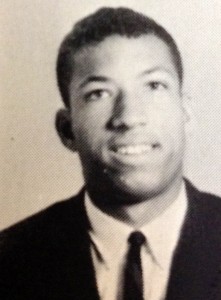

One foggy morning in late summer of 1962, a 17-year-old native of Washington D.C. arrived on the campus of what was then Eastern Mennonite College not knowing a soul. Grandison Hills’ parents had told him it was a clean school with no drinking, no smoking, no dancing, no TV, but with lots of fresh air and great food.

“I was already accepted to Howard University right here in D.C.,” Grandison Hill said in recent interviews with two EMU writers. “But my father knew I was hanging with the party crowd, and I’d be doomed academically if I went with my friends across town to Howard.”

Hill’s parents had learned about EMC from relatives living in Luray, Va., “a hoot and a holler” from Harrisonburg. “My uncle was a master barber in Luray. He and my aunt knew black folks in Harrisonburg, who knew what kind of folks they [the Mennonites at EMC] were.” Bingo! The Hills were seeking “a Christian experience without social distractions.”

Jolting adjustment, but no quitting

The academic and socio-cultural scene Hill found when he arrived on the Harrisonburg campus was a jolting cross-cultural experience for a city-raised African-American teen. He had a girlfriend back home, a love of dance parties, and a repertoire of easy-flowing curse words from the usual trash-talking on D.C. basketball courts.

In 1962 at EMC, the percentage of white Mennonite students easily ran into the 90s, typically from rural backgrounds. Hill was one of four U.S.-born black students enrolled in EMC, based on photos in that year’s Shenandoah yearbook. All faculty men were required to wear plain coats; all faculty women, the prayer covering and very modest dresses. Males and females did not publicly hold hands. Chapel attendance was mandatory every school day.

Now a successful trial lawyer in D.C., Hill stayed at EMC only one year. “My pillow was wet many a night,” Hill recalls, loath to disappoint his parents who had made huge financial sacrifices to put him at EMC. “My mother’s theme song was, “We don’t quit.”

Hill was the first-born of three sons, raised in a home headed by education-oriented parents who brought home middle-class salaries for those times. Howard University was six blocks from his home. “I walked through campus when going to junior high and to my favorite public swimming pool.” Next door was Arthur Paul Davis, a famed literary figure who taught at Howard and had earned his PhD in English from Columbia University. As a boy, Hill saw luminaries of the Harlem Renaissance – James Baldwin, Langston Hughes, Gwendolyn Brooks – relaxing on Davis’ front porch. Another neighbor was Thomas H. Countee Sr., the first African-American to get a PhD in physics (earned at a Dutch university, as Hill recalls).

Preparing for success

In short, Hill was surrounded by upwardly climbing folks who were preparing their children to continue to challenge racial barriers. Hill’s father was a businessman and employee of the U.S. department of defense; his mother managed a D.C. playground. When Hill said he hoped to become a basketball coach, his father angrily made it clear that Mom and Dad weren’t working themselves to death for such an aspiration. The Hill boys had just three options – to be a physician, dentist or lawyer. (Two ended up as attorneys, the other a dentist.)

The summer before Hill arrived at EMC, his father had scraped together the money to send him for six weeks to one of the best private schools in D.C., St. Albans, an Episcopal school that catered to well-to-do boys from (almost always) white families.

Hill took calculus and made friends with the son of a Swedish embassy official. “The academic experience at St. Albans was so tremendous. It was a great experience – the guys at St. Albans accepted me. It was so relaxed and so much fun – they didn’t have that religious thing on them.” St. Albans offered Hill the option of enrolling in a post-secondary school year, which he desperately wanted to do. But it was beyond the financial means of his family; EMC was viewed as his next-best option.

Among Mennonite boys in Brunk

Hill dormed in the Brunk House adjacent to campus with a six Mennonite guys from various class years, with last names of Good, Driver, Ranck, Clymer, Reed. “We all had separate rooms and studied a lot. Many had part-time jobs. One guy would return from his job around sun-up and wake the whole house with a booming, ‘Good morning, world!’” By mid-fall, Hill was on the varsity basketball team.

Hill recalls “many impressive speakers” at daily chapels, which were different in style from his family’s Methodist church. “The first time I heard a cappella singing, tears literally rolled down my face. I had to pinch my eyes to keep from making a scene. I was stunned how beautiful it was.”

After chapel, came the highlight of Hill’s day: a cafeteria meal served family-style, three girls, three guys to a table, assigned randomly by number. “There was a rhythm and ritual to it, standing until all arrived, the saying of grace, the singing of a song, the passing of the bread to the right, the filling of water glasses. And then the pleasant conversation, getting acquainted around the table, each day learning to know a new set of students. By the end of the year, everyone on campus knew each other. And the food, like my parents promised, was always excellent.”

Encountering racism

Dean of men Alphie Zook had counseled Hill when he arrived on campus, “Not everyone here will welcome you. Unfortunately, you may encounter some racism.”

One racist encounter happened on a Saturday, when meals were not served family-style. After a morning studying in his room, Hill went to the cafeteria for lunch. He sat down with his tray at a convenient table where several other students had gathered. Conversation at that end of the table stopped when a guy diagonally across from Hill interjected, “You should be eating that meal on the back porch.”

Hill felt his anger rise to within a scintilla of striking back. “I thought how disappointed my parents would be if I was kicked out for fighting. I calmly laid my fork on the tray. I locked gazes with the guy, neither of us said a word. Eventually he looked away. I picked up my fork and continued eating.”

Other painful memories: The time a student got up and left when Hill came to a non-assigned table. Overhearing someone say, “What the h..l is he doing here?” when he walked by. Being called a “n….r” by a child in the presence of his Mennonite parents, who said nothing. A female student who met his eyes as they passed on campus, but seemed fearful of saying “hi.”

Getting support too

Yet Hill also experienced inter-racial solidarity. He described a time when he and a few schoolmates went downtown to see a movie, an activity that was then against school rules for everyone. “After we’d bought our tickets, the manager told the rest of the group, ‘You can sit in the regular seats, but he has to sit in the balcony.’ They all decided to join me in the balcony. About ten minutes later, the manager appeared upstairs, saying there’s an official from EMC downstairs looking for us. And he showed us a side door to exit. I knew he was lying, but we all left on the slim chance we’d be caught.”

The one place Hill could relax was playing sports, especially basketball on a team that traveled to play games at Goshen College in Indiana and Messiah College in Pennsylvania. He recalls two Yoder brothers, Paul R. Jr. ’63 (now a local eye surgeon) and N. Wayne ’66 (now a psychotherapist based in Florida), as tough competitors with serious talent.

One time in chapel, Paul helped Hill to navigate a cross-cultural snafu. “I was sitting at the back and someone up front said something that caused everyone to stand, look straight back at me, and kneel down with their elbows on their seats. This caught me totally by surprise. They’re all looking at me. Paul locked his eyes with mine and let me know I needed to do what he was doing.” (This method of praying is no longer practiced in modern Mennonite churches.)

EMC had a handful of students from Kenya and Tanganyika in 1963. “The international students from Africa didn’t know what to think of me; I was so different from them. And the average Mennonite kid had never been around a black guy on a daily basis. Should I act friendly or keep him at arm’s length? Or just treat him as a human being? For my part, I tried to never offend, to keep a smile on my face and be open to conversation.”

At first the coursework was tough for him. “Most of the Mennonite students were well prepared for the seriousness of the studies. I had to really buckle down and study hard. But I moved fast on an upward learning curve.”

Meeting the Lord

Hill’s biggest take-away, however, wasn’t in the academic realm. “It was here that I met the Lord. It was a combination of things that got me thinking. Everywhere I turned I’d find more evidence of the resurrection. The guys had an early morning prayer group. It wasn’t a devotional thing as much as learning from scripture, reading the stories in a deeper way. And coming to my own conclusion – He’s real!”

Before Christmas break 1962, Grandison Hill returned from class to his room to discover a box on his desk. He opened it to find a King James Bible, and inside the simple inscription, “The Brunk House.”

Despite meeting “many genuinely good people who did a lot to make me feel comfortable,” Hill felt lonely away from “my own people.” Bringing along his new Bible in the fall of 1963, he transferred to Virginia Union University, whose roots go back to the end of the Civil War, when the American Baptist Home Mission Society started offering classes to African Americans emerging from slavery. At Virginia Union, with a Baptist seminary at the heart of its campus, Hill got much of what his family liked about EMC, without the racial and cultural issues – “Virginia Union was small and everybody knew you and nurtured you – there was no foolishness or you would be sent home.” He majored in biology and minored in chemistry, then taught middle-school math for three years in his home city before going to Howard University’s School of Law on a full scholarship.

For more than half of his life, Hill has practiced as a civil and criminal defense trial lawyer, admitting he is addicted to the drama of jury trials. His home way from home is D.C. Superior Court. At 69, he is tempted to “reduce the case load a bit. But a serious jury trial is thrilling. You just never know the outcome; it’s so much fun with so many surprises.”

He has these lingering questions from his year at EMC: “Did anybody get anything from me? From their experience meeting me? Did it open anybody’s mind?

What a great article! Grandison Hill went through a very challenging time. I can’t even begin to imagine how difficult it must have been at times. But as the article points out, as Mr. Hill maintained his integrity “…Hill felt his anger rise to within a scintilla of striking back. “I thought how disappointed my parents would be if I was kicked out for fighting. I calmly laid my fork on the tray. I locked gazes with the guy, neither of us said a word. Eventually he looked away. I picked up my fork and continued eating…..”, Mr. Hill prevailed!

Living in Washington, D.C. I actually met Mr. Hill though very briefly and even though he wouldn’t remember me, I remember him as being a man who carried himself with dignity and confidence.

Great post, I enjoyed reading very much!

Grandison Hill,

Thanks so much for sharing what it was like for you during your year at EMC. I would have been in your class back in ’62, but I didn’t live in the dorm, and didn’t make the varsity team, so I don’t remember that our paths crossed, but helped to bring back the memories of EMC of that era. My impression at the time was that most of the students of color on campus were international students. I do remember that there was a “whites only” sign over the water fountain at the Rockingham County Court House, Harrisonburg High School was segregated, and there was a separate Mennonite Church in Harrisonburg for the “negro” Mennonites. When I look back on my years at EMC, 1962- 1966, I realize that it was at the height of the civil rights movement, yet I do not remember having a single lecture or class discussion on Civil Rights or racism. I do remember learning after the fact that Professor Harry Lefever had secretly attended the Martin Luther King, Jr. March on Washington in 1963, but if he invited any students to join him, I was not one of them.

That era was also at the beginning of the Vietnam War, and EMC did an excellent job of teaching that war was wrong, and that the followers of Jesus used only the “weapons” of love and truth in responding to violence and war, and I ended up doing my alternative service to the military with MCC in Vietnam, doing literacy work with Vietnamese children who had lost their schools due to the war. As to why we were not better educated about Jesus’ radical acceptance of people of all races, and Mennonite agencies were not offering voluntary service positions doing voter registration in Harrisonburg and across the South, or working with the Poor People’s Campaign, perhaps others can explain.