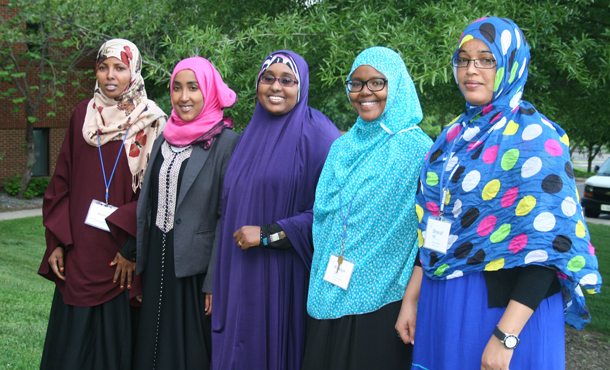

It’s a diverse group of five women. Among their many roles and areas of expertise, one can find law, information technology, business administration, political advocacy, rehabilitating youth with the UNDP, and a graduate degree in gender and development. In common are their Somali ethnicity, Muslim faith, and burning desire to prepare themselves and nurture other women for playing major roles as peacemakers.

To accomplish this, they gladly accepted USAID assistance to be part of the 2013-15 Women’s Peacebuilding Leadership Program. They started with attending several sessions of the 2013 Summer Peacebuilding Institute (SPI) at Eastern Mennonite University (EMU). They then will return to their home regions where experienced leaders in the peace field will mentor them, helping them to integrate their academic training with their day-to-day work. At the end, they will earn a graduate certificate in conflict transformation conferred by EMU.

In this first leg of their program, the five ethnically Somali women travelled more than 8,000 miles from their homes in East Africa – Kenya, Somalia and Somaliland – to Harrisonburg, Va., to attend SPI in May and June. Course topics included conflict analysis, peacebuilding practice, restorative justice, and trauma awareness & resilience.

Inspired by Dekha Ibrahim Abdi

“I heard about the program from people who came here before,” said Rukiya A. Aligab, 26, born in

Kenya of Somali parents. One of those people was Dekha Ibrahim Abdi, a childhood friend of her mother’s. Abdi studied and taught peace at EMU a half-dozen times from 1998 until she died in a car accident in 2011. As shown in a 1998 documentary, The Wajir Story, Abdi was an exceptional leader of peacemaking efforts in Wajir, the northeast section of Kenya, bordering on Somalia.

Weeks before her death, Abdi participated in a brainstorming session in the summer of 2011 at EMU that eventually resulted in the launching of the Women’s Peacebuilding Leadership Progam in the summer of 2012.

“I wish Dekha could see the inspiring, energetic women following in her footsteps,” says Jan Jenner, who was a close friend of Abdi’s. Jenner directs this new women’s program lodged under EMU’s Center for Justice and Peacebuilding. “Her dreams are coming true.”

Aligab notes that the women’s group led by Abdi gave rise to an official “district peace committee” in Wajir, in which women play key decision-making roles. This model has since been replicated throughout Kenya.

Conflicts over land, water, resources

Nimo Somo, 26, was born in Wajir a few years after the Wagalla Massacre, a devastating event recently

acknowledged by Kenya’s Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Committee. (Vice-chair of this committee is Tecla Wanjala, who earned her MA through the EMU program in 2003.) The massacre happened on Feb. 10, 1984. Soldiers employed by the Kenyan government rounded up ethnic Somalis from a certain clan, tortured them, and killed about 5,000. Somo’s grandfather escaped being killed, but was left permanently paralyzed from the waist down.

Officially, the Kenyan soldiers had been dispatched to stop inter-clan warfare over land for grazing cattle. Not surprisingly, warfare continued after the massacre, since the roots of the regional conflicts had not been addressed, perpetuating trauma upon trauma.

“There’s a scarcity of resources [in Wajir],” says Somo, a lawyer who finds peace work more energizing than preparing legal briefs in an office. Land is needed by the 80 percent of the population that relies on moving livestock from one grazing area to another. With climate change, droughts and famines have come more frequently. When the scarcity becomes politicized, says Somo, the region explodes with killing.

“For 22 years, we are in war,” says Amina Abdulkadir, 27, who is a native of Puntland, a semi-autonomous state in the northeast corner of Somalia. Throughout the region, “the problems are the same: sharing power and resources, mainly land and water.”

Women from all clans rank among the biggest victims in the struggle over power and resources, she adds. “We need a role, but it is denied. My dream is to train women in peacebuilding and reconciliation.”

Abdulkadir credits the recently elected president of Somalia, Hassan Sheik Mohamud, with making an effort not to favor one clan over another and with appointing two women to high government offices. Mohamud attended the Summer Peacebuilding Institute at EMU in 2001.

Sharing wisdom, lessons at SPI

Nimo Farah, 30, comes from Somaliland, a region that functions as an independent state with its own capital, Hargeisa. She began her journey toward being a civil society leader as a high school activist in 2003. At EMU, she prizes the opportunity to have cross-cultural exposure to an array of other peace practitioners from around the world, where they can borrow from each other’s good practices and adapt them to their own contexts. (Read Steven Hakizimana’s story for an example of a fellow SPI participant.)

The experiential style of teaching and learning used at EMU also intrigues her. She says her seven-day class in how to design learner-centered trainings has inspired her to introduce youth-focused dialogue education to Somaliland and to seek a part-time teaching role at the University of Hargeisa where she also will use her newly acquired skills.

Farah and several other women voiced measured appreciation for traditional decision-making circles consisting of elderly and presumably wise men, but added that the days of women being seen and not heard, and of youth being treated as if they had nothing to offer, needed to be relegated to the past.

Grateful for USAID’s support of women

Hinda Hassan, 30, of Somaliland, who works on improving the prospects of youth and women through UNDP training projects, became interested in peace while working as an IT specialist for a project called Observatory of Conflict and Violence Prevention. She credited USAID for making it possible “for Somali women to stand up and demand change. In the Somali culture, it is always men who have the say. Now it is our time.”