Senior social work major Elisabeth Wilder spent 12 weeks last summer working for peacebuilding organization Justapaz in Bogota, Colombia. A grant from Eastern Mennonite University’s Peacebuilding and Development Department funded her time in South America, where she worked for the NGO’s radio show, “Sintonizate con la Paz” (Tune in with Peace), among other responsibilities.

Joining Wilder in Colombia were four other EMU students, each placed with a different peacebuilding group: Alyssa Moyer, with Edupaz in Cali; Liana Hershey, with Sembrandopaz, Sincelejo; Hannah Mack-Boll, Mencoldes, Bogota; and Anna Messer, Creciendo Juntos and Pan Y Vida, Soacha.

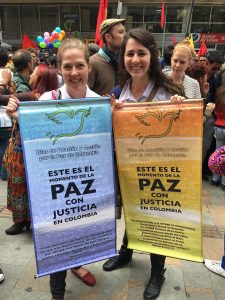

In a recent blog post for The Mennonite, shared below with permission, Wilder writes about joining her colleagues and other revelers in the streets of Plaza Bolivar to celebrate the June 23 signing of the bilateral ceasefire agreement between the national government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC).

Next semester, Wilder will be the Central America and Colombia Security intern with the Latin American Working Group, while she lives and studies at the Washington Community Scholars’ Center. Through staying updated on Colombian news and participating in peace vigils, Wilder continues to be an ally for Colombian peace efforts. She is interested in a career as an international human rights attorney

“I’m hoping to return to Latin America soon and continue learning and doing whatever is in my power to help,” says Wilder.

‘Asking for the Impossible: A Lesson from Colombia’

This summer I had the privilege of working at a human rights office called Justapaz (just peace) in Bogota, Colombia in the midst of the final negotiations of the Colombian peace accords.

The Colombian government has spent the last six years trying to negotiate a peace deal with the largest guerilla group in the country, the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarios de Colombia (FARC or the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia). In the midst of these negotiations came a historic day: the signing of a bilateral ceasefire between the Colombian government and the FARC, signaling an end to over 50 years of war.

In our matching white t-shirts, my coworkers and I left the office on the day of the signing of the ceasefire to go to Plaza Bolivar to celebrate with other Colombians in the midst of making history. Surrounded by chants of “viva la paz,” balloons, and the ecstasy of thousands of people celebrating a long-awaited end to war, we watched as President Santos of Colombia and FARC leader Timochenko signed these peace accords.

I cannot even begin to describe the extreme honor it was to share in the joy of generations of people who have only known war seeing the beginnings of peace. There is no ink nor code that will ever capture the sanctity of that moment that will forever live in my heart.

When the buzz of the crowd died down, my coworkers and I returned to the office to celebrate within our smaller community. We sang, gave thanks to God and shared our reflections on this blissful moment. The director of Justapaz, Jenny, gave the first words of our celebration.

Jenny talked about how, 12 years ago, she joined a campaign called Pan y Paz (Bread and Peace) to pass out bread to Colombian people on the International Day of Peace as a sign of goodwill and hope for peace. Twelve years ago, the idea of peace in Colombia seemed all but impossible. After decades of war and in the midst of Plan Colombia, all seemed hopeless back then; yet today here we all sat celebrating the end of the war. Jenny’s eyes teared up as she looked around the room in astonishment and disbelief of the moment.

“It’s not unreasonable to ask for impossible things,” she said.

After walking alongside people who hoped when all seemed hopeless, acted for justice at their own expense, and built peace from the ground up, it’s been hard adjusting back to a culture of pragmatism, utilitarianism and sometimes apathy here in the United States.

Faith in the United States often is less a matter of conviction and more a means to get through our day. This often causes me to ask the question, what does being a person of faith really mean in our context?

Faith is asking for impossible things.

It’s asking for reconciliation after what is seemingly the worst election in our history. Faith is daring to wonder what a world might look like when people with differing views and lifestyles can come to the table in peace. Being a person of faith is thinking beyond the reality we live in.

In this season of cynicism, this age of agony, and this time of trouble, I cannot help but be hopeful, not because of the security of my place in heaven, but because the impossible is coming on earth.

“In the world, but not of the world” is no longer a phrase referring to my eternal citizenship, but rather the idealism and optimism that the improbable can happen on earth when logic and reason would state otherwise.

Colombia is still waiting for peace. They have yet to implement the peace accords (the plebecite vote failed by a narrow margin), negotiate a peace deal with the Ejercito Liberación Nacional (ELN) National Liberation Army and ensure justice for those who have been affected by the war.

But when you look at the peacemakers–individuals who are protesting, camping out in the streets and fighting for peace with every ounce of their spirit–how could you not believe in something beyond this world?