For the Chinese scholars at Eastern Mennonite University this semester, witnessing the difference between Chinese and American educational systems has been enlightening.

“In China, students are willing to listen to professors lecture,” says Yan Wang. “Here, there are a lot of group discussions. It is good for creative thinking. Every student has their own idea.”

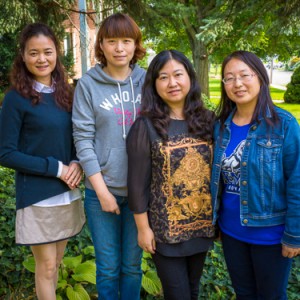

Wang is one of ten Chinese scholars visiting EMU from Sichuan Province as part of a “visiting faculty” program. Eight are sponsored through Mennonite Partners in China (MPC), an exchange program that has been thriving in various formats since the early 1980s. The other two are on scholarship from the China Scholarship Council, a competitive, state-funded scholarship fund for research and study abroad.

For 16 years, Mennonite Partners in China has placed English teachers from the United States at Sichuan University of Arts and Science and many other schools. In turn, Sichuan sends visiting scholars to EMU. A cross-cultural group from EMU, co-led by MPC director Myrrl Byler, is currently in China (visit their cross-cultural blog).

The agreement between the Sichuan university and EMU was formalized in January 2015. Administrators hope the agreement will facilitate “academic exchanges, scientific research cooperation, and communication between teachers and students.”

Sichuan province is in Southwestern China, a region Wang describes as “developing.” She says English teachers there have little opportunity to study the language in an immersion environment.

Teaching, learning, research

Here at EMU for the fall semester, the scholars are working on research projects, perfecting their spoken English, and auditing classes about world literature, writing, and methods of language teaching. Some of the scholars will analyze the teaching techniques they observe in research papers that they will eventually publish on subjects as varied as the difference between the writing of Chinese and native English speakers and differences in American and Chinese teaching methods.

English professor Mike Medley is the on-campus liaison for the visiting faculty, which means, among other activities, he organizes a picnic when the group first arrives and a farewell luncheon at the end of the semester. He also provides an academic orientation, a campus tour, an explanation of the academic schedule and helps the scholars connect with “friendship families” so they have an opportunity to interact with the local community.

The scholars also interact with EMU faculty at all university-sponsored faculty events and are often invited into classes to speak. Among those professors who have extended invitations to former and current groups are visual and communication arts professor Cyndi Gusler and English professor Marti Eads. Nursing students have also benefited from visits to their classes.

“It’s a quite different educational experience,” says Liu Yang of her time so far. One of the biggest challenges “is learning how to manage our time.”

Wang agrees. “In American colleges, the students have to read a lot. In China, the students read, but not as much…there is a lot more out-of-class work here.”

Sabbatical helps busy teachers ‘recharge’

Hongjuan Tang has been teaching English for more than 20 years and, except for a brief visit to the United States for her son’s undergraduate commencement, had never been to an English-speaking country. Shuli Chang, too, visited Canada and Australia for brief periods. Out of the group, these two teachers were the only scholars to have traveled to an English-speaking country in the past. For both teachers, coming to EMU not only places them in an English-speaking environment, but also acts as a much needed sabbatical to “recharge” and further develop teaching expertise.

Back home, “I’m working on a nationally-funded research project studying the relationship between environment and children’s language competency in western China,” she said. At EMU, she has the time to work on her project and access research resources not available at her home institution.

In part, the lack of research resources may be because of the rapid expansion of Chinese universities. “In the ’80s and ’90s, most universities had 2-4,000 students,” said Byler in a recent email. “With a 10-year expansion, most of these universities have grown to 30- and 40,000 students.”

As a result, class sizes in China are normally large and professors become used to teaching to an exam in order to cope. Poorer provinces, such as Sichuan, don’t have the resources to reform.

“There is a gap in inequality between the big and small universities,” said Yang.

Tang agrees. “This program is a very good thing for the western part of China because it helps with development.”