The Nelson Good House in Washington, D.C. Photo by Jon Styer.

Washington Community Scholars’ Center

In the fall of 1976, Phil Baker-Shenk arrived in Washington D.C., intending to advance the causes of international human rights and nuclear disarmament through an internship with the Friends Committee on National Legislation. However, as an 18-year-old college undergrad at the bottom of the organization’s rungs, he found himself shuffled to its underfunded and understaffed Native American advocacy program.

He didn’t know it yet, but the assignment sparked an interest that was to become his life’s work.

After graduating from EMU in 1979, Baker-Shenk worked for two years for the U.S. Senate Committee on Indian Affairs before earning his law degree at Catholic University in D.C. He then returned to working on issues affecting Native American tribes, including three more years as an aide in the U.S. Senate. Now a partner in the Holland & Knight law firm, for the past 25 years he has been representing tribal governments across the country facing a variety of challenges to their sovereignty and self-governance authorities. It all goes back to that formative year he spent in Washington, which almost didn’t happen in the first place.

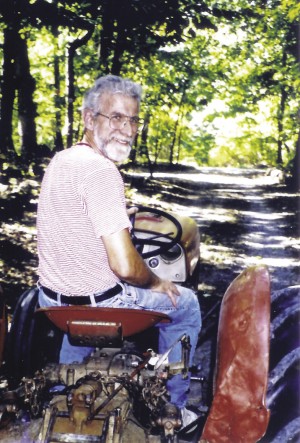

Nelson Good on a tractor at Rolling Ridge, where he and his family sought occasional respite from the intensity of living in D.C.

The idea of an EMU-sponsored academic program in D.C. began with Nelson Good ’68, who spent two years after graduation in D.C. as a conscientious objector volunteering at a community center. He later became an administrator of two Mennonite-run voluntary service units in Washington and soon became convinced that a service-year experience would be improved if a formal academic component were added.

Good approached EMU with his idea, but it was not immediately embraced by the administration. The college was facing a period of financial uncertainty in the mid-’70s, and was hesitant to start such an innovative program. This came as a disappointment to Baker-Shenk and a group of students who had become excited about Good’s proposal. They decided to take matters into their own hands in the spring of 1976.

“We organized together, and said to the administration, ‘We’re going to go elsewhere unless EMU starts this program,’” remembers Baker-Shenk.

Their effort paid off, and the university took a gamble on the idea. Good became the first director of the Washington Study-Service Year (WSSY), a position he would hold for the next 11 years, and Baker-Shenk was one of the first nine students in the first WSSY program during its initial year, from 1976 to 1977.

“Thanks to EMC’s vision, and thanks to WSSY and Nelson Good, I stumbled into a life-long passion and vocation that I would have never predicted ever happening to a little Mennonite farm kid from Pennsylvania potato fields,” Baker-Shenk said.

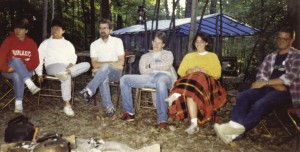

Nelson Good in 1987 with college students at Rolling Ridge, a rustic retreat center in West Virginia regularly used by WCSC. From left, Deborah Weaver ’89, Kay Zehr’ 87 Diller, Nelson Good ’68, Craig Snider ’88, Mary Jo Swartzendruber (class of ’89), and Steve Mumbauer ’88

From the beginning, the WSSY program (renamed the Washington Community Scholars’ Center, or WCSC, in 2002) was structured much like it is today. Students lived together in a group house and split their time between internships and academic courses, either taken at universities in the D.C. area or taught by EMU faculty staffing the program. Throughout its history, the program has afforded students the opportunity to live, study and gain valuable, real-world work and cross-cultural experience in the middle of one of the world’s most important cities.

“It was just such a thrilling year on multiple levels for me,” said Rolando Santiago ’79, a student during the second year of the WSSY program, beginning in the fall of 1977. “When I look back on it, I’m not sure that I’ve ever had such a rich, stimulating year since.”

Now the executive director of the Lancaster Mennonite Historical Society, Santiago said his internship with Ayuda, a legal aid agency that primarily served Hispanic immigrants, gave him “deep appreciation for, and understanding of, the role that community-based organizations can have in enriching the life of an entire population.”

He said that mindset also heavily informed his work in mental health for the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and as executive director of Mennonite Central Committee U.S. from 2004 to 2010.

Originally from rural Puerto Rico, Santiago got his first taste of urban living in Washington, and intentionally stretched himself by taking courses at the University of Maryland that weren’t available then at EMU. He also became involved in the Hispanic Mennonite Church in D.C. and capitalized on the spontaneous learning opportunities he encountered, such as a course he took on Marxism and Leninism taught by a person he’d met through Ayuda.

“It was a bit scary for me because I was always taught that that was not something you touch, intellectually or otherwise,” said Santiago, who later expanded his housemates’ horizons by arranging for the teacher to give a lecture on Marxism to the entire WSSY program.

One of his classmates that year, Dawn Longenecker ’80, also described the experience as one that stretched, challenged and transformed her in important ways.

“It’s a really wonderful place where people can struggle and grapple and build community all at the same time,” said Longenecker, director of Discipleship Year, a voluntary service program in Washington D.C. run by the Church of the Saviour.

As a WSSY student, Longenecker discovered a lifelong passion for advocacy and social change through her internship with the Gray Panthers, a grassroots organizing and advocacy group for elderly people. Longenecker recalls wrestling with the other WSSY students over questions of faith, justice and application of the Gospel, and said her mind was “blown on multiple levels.”

“It was an incredible year,” said Longenecker, who has remained in Washington ever since, mostly doing social work. “My whole life journey came from WSSY. My whole life was transformed.”

The formal academic component of the program includes classes taught by WCSC faculty, plus the option of studying at a number of different universities in the Washington D.C. area. At the beginning of the program, the University of Maryland was the main partner institution; today, students can enroll at Trinity University, the University of the District of Columbia, the Corcoran College of Art and Design and others, including Howard University and Catholic University.

Students are also required to take a weekly academic seminar. Until recently, WCSC director Kimberly Schmidt taught some seminar topics, while former associate director Doug Hertzler ’88 focused on others. (At the end of the fall 2012 semester, Hertzler departed WCSC for another job.) Schmidt and Hertzler – whose academic specialties are history and anthropology, respectively – used the city as a giant textbook as they examined issues of race, class, urban life and faith.

“The cultural and historical studies at WCSC have greatly informed my life,” said Mark Fenton ’10. “Looking at the gentrification of D.C. and issues of race and politics during the history of the city, has made me a more informed and better-rounded person.”

WCSC also represents EMU’s longest running cross-cultural, established several years before cross-cultural education found its way into the university’s required curriculum. When the program began, about 70 percent of Washington D.C.’s population was African-American, giving many students – particularly in the early days of the program – their first extended experience surrounded by people whose race and culture were different from their own, which tended to be largely white, rural populations.

“I remember the moment when I realized I wasn’t seeing race when I was working with kids,” said Dwight Gingerich ’81, who coached basketball at a predominantly African-American school during his year in the WSSY program. “Our neighborhood was 99 percent African-American, and it was a great cross-cultural experience for me.”

While many WCSC students today also participate in other cross-cultural programs offered at EMU, the program in Washington still fulfills that requirement for students.

Many alumni recall the importance of the informal, day-to-day aspects of the experience.

“I’m much more confident in finding my way around places, because I biked all over the city, and finding my way around transit systems isn’t so daunting,” said Fenton.

Amy Smith ’90 Mumbauer remembers learning about the challenges of sticking to a tight budget while shopping for her 12-student house at the Shoppers Food Warehouse and Glut, a food co-op. Like most WCSC groups, hers shared cooking and cleaning duties. They ate together around a long wooden table beneath a ceiling occasionally dangling spaghetti – the result of tests for pasta done-ness.

By the late ’90s, the WSSY program was beginning to have trouble filling all its spots, facing competition from EMU’s growing cross-cultural program and increasingly rigid academic requirements that made it difficult for students to spend an entire year off campus. Even with a handful of students from other Mennonite colleges entering the program each year, low enrollment was a significant concern when Schmidt became director in 1999.

After two more lean years, Schmidt and others at EMU made a difficult decision to reduce the program from a year to a semester in length. With the “year” part removed from the WSSY equation, a name-change was also in order. They chose the term “Community Scholars” to emphasize the academic rigor of the program – one of its major distinguishing factors from the many other college internship programs that exist in Washington D.C. “Community Scholars,” Schmidt says, also connotes an emphasis on social justice, which has always been a focus of the program. Finally, “Center” was chosen to emphasize the partnership EMU has with other Mennonite universities that regularly send students to the Washington Community Scholars’ Center, or WCSC.

Today, Bluffton University in Ohio is EMU’s biggest partner school in the program, sending up to five students per year. In addition to two semester-long sessions each year, WCSC also offers a 10-week summer program that places more emphasis on the internship experience and allows students to accumulate the same number of internship hours as those who spend the whole semester in Washington.

“I really admire how EMU took a longstanding program and wasn’t afraid to redesign it in a way that more people would benefit from,” said Fikir Tilahun ’00 Sanders, a member of one of the last groups of students to spend two semesters in the WSSY program.

In 2006, the newly revamped WCSC program underwent another change. Faced with expensive and cumbersome renovations to the original building in northeast Washington, the program moved a relatively short distance to a new building on Taylor Street. The new home gave the program more space and more convenient access to a Metro station.

Nelson and contractor Jay Good at the newly purchased building for WCSC, not long before Nelson’s death of cancer in 2005.

The location also sits in an ideal neighborhood, neither sheltered nor unsafe. It is characterized by mixed incomes and ethnic diversity, said Hertzler. The diversity immediately surrounding the house, he added, made it very easy for students to conduct the direct participant-observation projects he assigned for the urban anthropology courses he taught.

The building is called the Nelson Good House, named in honor of the program’s founder and first director who was diagnosed with cancer as he was overseeing renovations of the new WCSC building in D.C. Good passed away in 2005, soon before the move was made.

Schmidt noted that the concept of “servant-leadership” remains at the heart of the WCSC experience and has been a core emphasis of the program since its inception. Servant-leadership, she explained, entails following Christ’s example in vocation by aligning faith and values with career goals; it characterizes the best leaders as motivated by a sense of service. In Washington D.C., she added, students have the additional opportunity to explore and apply Anabaptist values of servanthood and nonconformity in the geographic and figurative seat of American power.

“I came to understand in WSSY that institutions, and positions of leadership within institutions, are opportunities for serving,” said John Stahl-Wert ’81, who studied in the program during the 1977-78 school year.

The author of several books, including The Serving Leader, Stahl-Wert said that WSSY’s emphasis on servant-leadership, and a book the group read – Servant Leadership: A Journey into the Nature of Legitimate Power and Greatness by Robert Greenleaf – became the basis for his work today. In addition to writing, Stahl-Wert is also a leadership coach and speaker based in Pittsburgh.

“Criticizing institutions and leaders is one of the weaker – if sometimes necessary – acts of contributing good to the world,” he said. “We must step into difficult positions of responsibility.”

Stahl-Wert interned with the Juvenile Probation Office of the Superior Court of the District of Columbia. He recalls feeling immediately at home in the city even though he grew up in rural Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. During his WSSY experience, he said Washington D.C. became the first of many cities he now loves.

First exposure to big-city life is another important element for many in the WCSC program.

“I came to WSSY with very little experience in an urban setting,” said Trent Wagler ’02. “The first lesson I learned was that I’m a very, very small blip in this huge journey. . . . Coming from a small Kansas high school to a small Mennonite college campus, it was pretty easy to get an inflated sense of my importance in the world. My year in Washington put that into some perspective.”

Wagler interned with the Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company. That opportunity led to work as an actor and musician at a professional theater in rural Virginia, which later inspired his career now fronting his nationally touring band, The Steel Wheels.

With its interconnected emphases on learning and service, diverse opportunities for students to explore career interests, and location in the heart of a major city, the program exerts an impact on students in multiple ways, say alumni.

“My D.C. semester was one of the best choices I made at EMU,” said Fenton, who is now a media specialist with the Gravity Group in Harrisonburg. “It helped me focus my goals and work toward them, building myself as a person, as a professional, and more. I am very glad for every way that my time in Washington changed me. It has all been for the better.” — Andrew Jenner ’04