As with so many aspects of U.S. society and culture, the disaster relief community has its clear “pre-” and “post-9/11” periods. Back in the pre-days, the mentality and capabilities of organizations like FEMA and the Red Cross revolved around the physical needs of disaster victims: food, shelter and clothing. Within days of entering post-era, it became clear that the September 11 attacks pointed to the need for psychological support, not just physical assistance.

Within a week of September 11, 2001, Rick Augsburger contacted EMU’s Center for Justice and Peacebuilding (CJP). Then working in Manhattan as the director of emergency programs for Church World Service – one of the relief organizations facing a challenge it wasn’t well equipped to handle – Augsburger knew about the pioneering work that had been done at CJP of connecting trauma healing to the theory and practice of peacebuilding. Three days after the attacks, he placed a call to CJP to ask for help.

“We were the only conflict transformation program that had any trauma studies in the curriculum,” remembers Jan Jenner, who was director of the Practice Institute at CJP. Through Jenner, Augsburger invited CJP to develop a trauma-healing program in response to the terrorist attacks and pledged full funding for the initiative.

Two weeks after 9/11, CJP professor Barry Hart was in New York City meeting with Augsburger and his staff about a programmatic response to the tragedy. When Jenner and Hart shared the concept with other faculty members and staff at CJP, the group collectively developed an outline of what was to become Strategies for Trauma Awareness and Resilience, or STAR.

“I knew we would get strong commitment, high quality work and an ability to think outside of the box,” says Augsburger, a ’91 graduate of EMU who had previously worked with CJP on several trauma-related projects. “9/11 was something that none of us had experienced before, and we needed something different.”

In Augsburger’s eyes, CJP’s close institutional ties to the Mennonite church strengthened its ability to provide leadership in meeting the needs of traumatized groups. Religion, after all, was perceived as a major player in the events of 9/11, and leaders from a wide variety of religious traditions found themselves on the front lines of response within their own communities.

pioneered the link between conflict transformation and trauma healing in the 1990s, underpinned by his field work in Liberia and the Balkans. Photo by Jon Styer.

Putting together the pieces

“We had the pieces – trauma healing, restorative justice, a spiritual center – that we could put in place for the program that is now known as STAR,” says Jayne Docherty, a CJP professor of leadership and public policy who was involved in the program from its earliest planning stages. “Tapping the expertise of all the faculty members here, we were able to develop a holistic, integrative approach to the 9/11 crisis and its aftermath.”

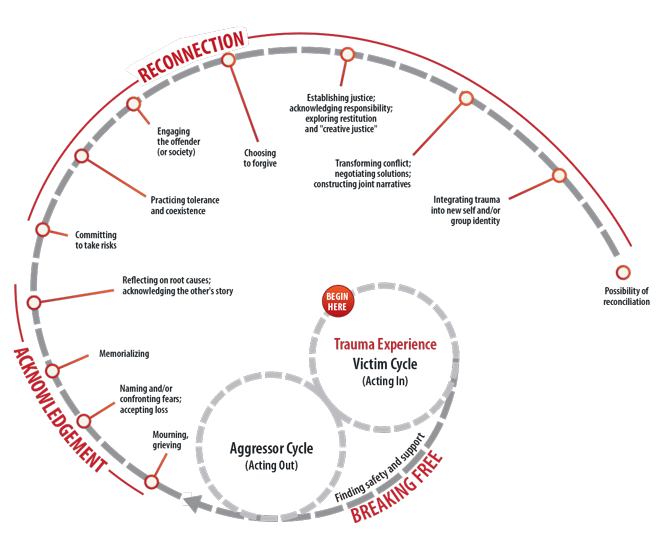

The first STAR workshop was held in February of 2002. As STAR’s founding director, Carolyn Yoder had woven the strands of CJP’s work and her own trauma-counseling expertise into a viable short-term program. While the format and materials have constantly been tweaked and revised, the major elements of that initial workshop have remained largely the same. Later that spring, Yoder adapted and expanded the diagrams used by Barry Hart and psychologist Olga Botcharova – who had worked together in the war-torn Balkans – into a three-part model of trauma healing. This model, including an easy-to-remember snail diagram (see below), remains central to the STAR curriculum.

From the beginning, the intensive, one-week STAR courses have included an exploration of the nature and effects of trauma on individuals and communities as well as study and discussion on the relationship of trauma-healing to the other key pieces of CJP’s peacebuilding framework, including restorative justice, security, mediation and conflict transformation.

A decade prior to all this, Hart was in Liberia helping lead trauma healing and reconciliation workshops for people affected by that country’s civil war. Hart, then pursuing a doctorate in conflict analysis and resolution at George Mason University, was working with the Christian Health Association of Liberia, which was very interested in addressing the psychological wounds suffered by so many people in the country.

“I was coming in not as a psychologist but as a conflict transformation person,” says Hart. “It became very clear to me that these so-called ‘ethnic wars’ not only had an identity aspect, but a significant psychological one.”

Pioneer in linking trauma to conflict

Hart ended up spending two years in Liberia. He used the dozens of trauma-healing workshops he conducted there as field research for a dissertation that was one of the first academic works to draw clear links between the fields of conflict transformation and trauma healing.

In the summer of 1994, Hart gave a presentation on his work at a peacebuilding conference at EMU (the forerunner of today’s Summer Peacebuilding Institute). It struck a nerve, leading to a class on trauma healing and ultimately to the subject becoming integral to the MA curriculum.

Over the next five years, Hart continued to integrate trauma healing and conflict resolution while working in war-ravaged areas of the Balkans. He returned to EMU’s Summer Peacebuilding Institute each year to teach on the subject. Hart usually co-taught the course with Nancy Good, a clinical social worker and trauma expert who was a member of the CJP faculty from its early years and who also played a key role in pioneering a connection between trauma healing on the individual level with peacebuilding on a larger scale.

“CJP takes a very interdisciplinary approach to peacebuilding,” says Lisa Schirch, a research professor at EMU and the director of 3P Human Security. “We recognize that people’s personal and emotional wounds need to be addressed in addition to the structural, economic and political changes that are required for peacebuilding.”

“Psychosocial trauma and peacebuilding” is now one of the five academic concentrations offered to graduate students at CJP, overseen by Hart, who joined the faculty full time after leaving the Balkans in 1999. Even today, CJP remains one of a very few graduate-level peace programs in the United States that places such an emphasis on trauma healing.

While the format and materials get tweaked constantly, the major elements have remained largely the same since STAR was launched in 2001. Photo by Jon Styer

Pushing edges of field

“In the 1990s, it was pushing the edges of the field to say ‘trauma matters,’ and it still is, as a matter of fact,” says Docherty. An important aspect of CJP’s trauma work is the recognition that “many of our students arrive traumatized, sometimes directly from ‘killing fields,’” adds Docherty, CJP’s new program director. “We have asked ourselves, ‘How can we support them?’ Giving them an education in trauma awareness and resilience is one way.”

Shortly after the inaugural STAR training, the program began to adapt its curriculum for different audiences. In 2002, Elaine Zook Barge interned with STAR as a graduate student to develop a Spanish-language version of the training. She helped lead the first Spanish STAR in November 2002 in Colombia; the first Spanish STAR at EMU was held the next month.

Another early adaptation was Youth STAR, designed by an international team of youth workers and intended to teach trauma skills to young people. (This effort was led by Vesna Hart, a native of Croatia who holds an MA in education from EMU.)

Grant funding from Church World Service supported the STAR program through 2005, by which time nearly 800 people from 38 states and 63 countries had participated in seminars on EMU’s campus, including the first sessions of Level II STAR. This advanced training prepares Level I graduates to themselves become practitioners, leading their own trauma-resilience workshops based on the STAR curriculum.

Given that the program had run longer and grown larger than many had expected at the beginning, CJP decided to continue STAR using a fee-for-service model. In 2006, as STAR grappled with the challenges of sustaining itself financially, Barge became the second director of the STAR program.

Adaptation, new directions and new partnerships have characterized STAR in the years since. Barge helped develop a Village STAR curriculum for use in settings where pictures tend to work better than lots of written words. Coming to the Table – now an associate organization of CJP that uses the STAR trauma-healing framework to address the legacy of slavery in the United States – also grew directly out STAR’s work at EMU.

Coming to the Table’s history-rooted twist on STAR led to Transforming Historical Harms, which looks at “historic traumas” that continue to inflict pain decades or centuries after a traumatic event or circumstance has ended (see article).

Global attention to trauma

emu.edu/cjp

STAR

Vernon Jantzi, a sociologist who directed CJP from 1995 to 2002, is the expert most often tapped by Elaine Zook Barge to co-facilitate STAR

trainings, whether on campus or internationally. Fluent in Spanish, Jantzi has introduced STAR to Mexico, Bolivia and Colombia. Photo by Jon Styer

From 2002 to 2007, STAR workshops were held in Sierra Leone, Liberia, Guinea, Uganda, Burundi and South Sudan. In 2008, CJP graduates working in Myanmar requested STAR assistance following a devastating cyclone. Also upon request, STAR went to Mexico in 2009, and Northern Ireland, Bolivia and Haiti in 2010 (for more on the work in Haiti, see this article).

The geographic spread of STAR has also occurred domestically. In Massachusetts, Beverly Prestwood-Taylor, a United Church of Christ minister and trauma-specialist who has taken courses at CJP, adapted STAR for veterans and their supporters into a two-day program called the Journey Home from War (see article). Donna Minter, a STAR alumna from Minnesota, returned home to found the Minnesota Peacebuilding Leadership Academy, which has hosted six STAR trainings since 2010 (see article).

Since she took over as director, Barge estimates that one-third of STAR trainings have taken place at EMU, one-third have been held elsewhere in the United States, and one-third have happened overseas. The total number people who’ve taken STAR trainings over the past 11 years is difficult to determine, given the proliferation of off-site trainings. What is certain is this: hundreds of individual STAR trainings have taken place on five continents, reaching thousands of people directly and rippling out far more broadly yet, as participants use the trauma-awareness and resilience principles in their personal and professional lives.

Rick Augsburger, whose phone call to CJP days after 9/11 led to the creation of STAR, says the disaster-relief community today is far better prepared to recognize and address the psychological impacts of disasters. While STAR can’t take full credit for that, it played an early and important role in introducing trauma awareness to these groups, says Augsburger, now the managing director of the KonTerra group, a consulting firm based in Washington D.C. that focuses on improving clarity, resilience and learning in domestic and international organizations. Growing awareness of and interest in trauma-related issues extends beyond disaster-relief agencies (see article).

“Because of the work we’ve done over the last 18 years here, people have started to pay attention to trauma,” says Barry Hart. “The major funders out there are becoming more and more aware of the need to incorporate trauma elements into the larger peacebuilding framework.”

Looking ahead, this new, wider interest in trauma awareness represents an opportunity for STAR to provide consultation, trainings and workshops to equip organizations with staff who are able to do trauma-sensitive programming (see article). “As more individuals want to share STAR with others, the program is facing the challenge of making sure that what others call STAR includes the complex mix of psychosocial trauma healing, restorative justice and conflict transformation components that make STAR unique,” says Jayne Docherty, incoming program director for CJP. “We’re working on a process for certifying STAR trainers and practitioners that will be available to students in the MA program as well as to other individuals.”