When a few of us on staff and faculty at the Center for Justice and Peacebuilding (CJP) came together last year to begin discussing the possibility of doing an online course – something we had never done before – we were met with some resistance, not the least of which came from Howard Zehr, Professor of Restorative Justice at CJP and a pioneer in the field.

Fast-forward one year: Howard and Brenda Waugh (MA ’09) are now three weeks into teaching the class, “Recovering the Vision: Conversations on Restorative Justice,” which is being carried out completely online. The students – all practitioners – hail from diverse locales in North America, Europe, and Australia. First-year MA student, Jenn Bricker, and I have had the pleasure of helping Howard and Brenda facilitate this course. And from deep skepticism, Howard has now become a strong advocate of the possibilities of CJP doing more online. What happened in the course of that year?

Relationality

Perhaps the strongest hesitation to implement an online course came out of CJP’s emphasis on embodied relationships. Restorative justice, in particular, is keen on the importance of encounter; of victims and offenders, but also of teachers and students. Circle processes, something practiced and taught heavily at CJP, are also predicated on there being a relational connection in the process. As we surveyed online educational practices at Eastern Mennonite University, we noted their asynchronous (out-of-time) nature, usually following a message board model where teachers would assign students postings by a certain date to which others would then respond and discuss in the comments. What’s lost here, though, is people’s faces, voices, and gestures, a whole cluster of non-textual expressions that help establish and nurture relationships. We simply couldn’t imagine doing a course in a text-only, asynchronous medium and have it maintain any semblance of the “CJP feel.”

Co-creative learning

Another hallmark of the CJP that was difficult to imagine happening in an online space was CJP’s elicitive pedagogical practices. The traditional Western approach to education has been variously described as a “banking” or “transfer” model by Freire and Lederach, respectively[1]. This view sees students as empty receptacles awaiting knowledge-as-information and teachers as the purveyors of such knowledge. This view limits the horizon of education, shutting off possibilities that open up in a more holistic, relational, co-creative approach to education, what Lederach calls “elicitive.”

One characteristic of how elicitive education gets done at CJP is through small group activities and projects that engage different learning styles, including artistic expression. The very nature of a text-only online environment privileges the banking model and limits modes of expression and different learning styles. So again we were not enamored with the idea of carrying out a CJP course in this fashion.

So what did we do?

To address these challenges, we investigated emerging edges of online communications technology. Software platforms are emerging which facilitate synchronous (within time), mixed-mode (audio/visual and textual) interaction within a virtual meeting space, in our case a classroom. So we strung together a curriculum that makes use of both synchronous and asynchronous technologies.

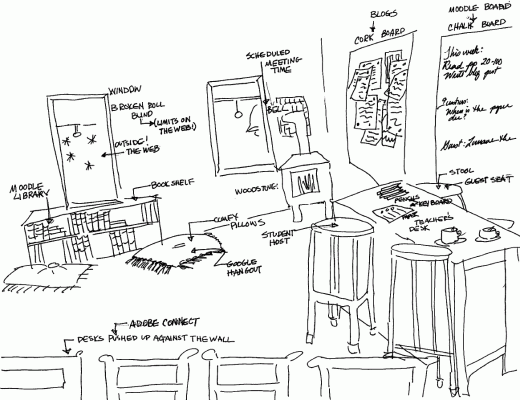

Every other week the whole class meets together for two hours in a virtual classroom using Adobe’s Connect platform. Within that space we’ve found ways to simulate circle processes, host special guests, and let students interview and discuss. You can even “raise your hand” to ask questions. A text chat conversation is going on the whole time, which then gets saved and posted with other class materials to Moodle, a widely-used open-source course management system. After the first class session, small groups were formed based on sub-interests within restorative justice. These groups will stick together through the remainder of the course. On weeks alternate to the large-group meeting, these small groups meet in Google’s new Hangout software. Then, before the next week’s full-class meeting, each small group is to post something to their group’s blog, using Google’s Blogger platform.

Both Connect and Hangout have the ability to be used by mobile devices such as the iPhone or iPad. So one student a few weeks ago joined her small group via her iPhone during a break in jury duty, something she was afraid would require her to miss her group’s meeting. Jenn and I would periodically drop in on the various Hangout sessions underway to see if things were proceeding well, and here was this student hovering over her iPhone in a courthouse, talking about restorative justice!

Limitations, as always

While the experience of helping conduct this online course has been one of the highlights of my career as a technology worker (and fledgling teacher), it has not been without its hiccups. Using a string of cutting edge technologies raised the bar in terms of tech requirements, for students and instructors alike. Streaming video over the internet takes a lot of horsepower on the student’s machine and a lot of network capacity across “the cloud.” Actively seeking international student-practitioners for this course was difficult, partly for that reason since high-speed internet is far from a given in many countries and not everyone has a fancy new computer or iPad. Also, it took extensive training efforts for students and instructors both since so few people have used software like this. Finally, cutting edge technologies have a tendency of not playing well with other cutting edge technologies. The number of “moving parts” in this course is somewhat dizzying, making troubleshooting inevitable technology issues a challenge, as I try to keep the “frame” as invisible to the students as possible, so we’re focused on restorative justice and not the tech and its limitations. We’ve had a few glitches small and large but so far nothing that has completely derailed the course.

But as I noted at the beginning, even our strongest skeptic, Howard Zehr, is feeling energized about what we’ve been able to accomplish so far in this course. I’m confident that as these technologies become mainstreamed, their glitches will be ironed out and a smoother experience will be possible. I’m proud to be a part of this team that has basically taken CJP’s teaching into the 21st century. Despite all the legitimate concerns we had at the outset, a creative solution was envisioned and implemented, and so far it’s showing tremendous promise for the future.[2]

Notes:

- Cf. Freire, Paulo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. 30th Anniversary ed. New York: Continuum, 2006; and Lederach, John Paul. Preparing for Peace: Conflict Transformation Across Cultures. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1996.

- While also signaling toward all the warning signs on over-use of tech and social media, and its impact on the very embodied relationships we value at CJP. For instance, this popped up in my twitter feed as I was writing: Facebook rehab via Al-Jazeera.

[Brian Gumm, MA ’11, is the Web and Information Systems Coordinator for the Center for Justice and Peacebuilding. Brian is also in his final semester of Mdiv studies at Eastern Mennonite Seminary. After teaching conflict transformation last summer in Ethiopia – and currently teaching it at a nearby college – Brian has been on a pedagogy kick and is thrilled to be mixing that up with his tech nerd skills at CJP.]

[Brian Gumm, MA ’11, is the Web and Information Systems Coordinator for the Center for Justice and Peacebuilding. Brian is also in his final semester of Mdiv studies at Eastern Mennonite Seminary. After teaching conflict transformation last summer in Ethiopia – and currently teaching it at a nearby college – Brian has been on a pedagogy kick and is thrilled to be mixing that up with his tech nerd skills at CJP.]

Thanks for using my photo – love your adaptation!

My pleasure, Jonathon! The koru is a favorite symbol of Howard Zehr when he talks about restorative justice, so it’s the first thing I went looking for on Flickr. I really appreciate you putting it on there under CC license! Thanks!

As a participant in this class, it has pushed me to shake off my neoludite tendencies.

I am impressed on how we can connect with students and presenters from around the world with out the expensive of traveling to one location. The technology however permits to many conversations at times. The text chat during the actual presentations in class is some times a distraction to the importance of deep listening. Are we over stimulated by simultaneous conversations to really listen well?

Thanks for the feedback, Nathan. We’ve talked about that chat window and I’m somewhat with you. Perhaps one way to look at it is to consider the embodied classroom equivalents. For instance, at CJP there are a number of people who knit while there’s a class lecture going on, and I happen to be a life-long notebook doodler in the classroom. So even in embodied classroom situations there’s a lot of potential for distraction but also ways to channel that distractibility toward pedagogically good ends.

There’s also the notion of having been trained in a digital environment where a chat window is somewhat of a normal fixture. At 32, I’m an almost-digital native, the internet becoming widely available when I was in high school. The chat room for the digital native is, well, quite native! :) Now, this doesn’t get us off the hook, because it can be abused, but I don’t think we’ve crossed that line in our class.

It could be said that one reason I save chat transcripts and post them on the Moodle site is to have a record of conversation. So by students and instructors can reviewing it, we’re able to see how well we used it, and adjust accordingly.

Thanks again, Nathan, both for your feedback and for participating in this fun experimental learning endeavor!

I just finished a one-year 100% online certificate in Restorative Justice through a university in B.C., Canada. It was definitely a mixed experience and did seem highly ironic to talk so much about community and presence when we never met throughout the whole year. You may have different technologies but we didn’t even go online at the same time – basically we just used message boards and for me it was rather a dissatisfying medium.

If you can generate a simultaneous online experience, which it sounds like you are doing, that will help a lot. It will never be as good a learning environment as a classroom, in my opinion, but it facilitates learning for people who may not be able to come to another location, and that’s a good thing. At Vancouver School of Theology where I am now, there is the option to attend classes by skype which is also good for students in other countries who skype in. It’s not perfect, and still not like being there, but again, it does help.

Wishing you “luck” with this process!

Thanks, Emma, for your candid reflections on your own experience with online RJ education. I’ve also been a part of message board-only and message board+classroom (hybrid) courses, some being decent experiences and others being pretty disappointing.

By using synchronous technologies, it’s our hope with this class to remove some of the “irony” of talking about community but never actually seeing each other. Incorporating the values of restorative justice into the teaching and learning experience itself was very important to us.

Best wishes to you and your current studies!