One cost of harsh punishment

The need for new approaches to school discipline came to the attention of tens of thousands in the nation’s capital when The Washington Post ran the headline “Fairfax school disciplinary policies scrutinized after apparent suicide.”

It was January 22, 2011, and the opening paragraphs of the newspaper article read:

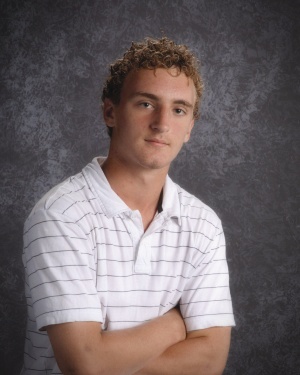

The apparent suicide of a 15-year-old high school football player in Fairfax County has sparked concern about the school district’s disciplinary policies, which critics say are overly punitive and often debilitating for students.

The concerns come as students at W.T. Woodson High School mourn the loss of Nick Stuban, a former sophomore running back on the junior varsity team. Football players wore their homecoming jerseys in memory of the well-liked teen Friday, and many other students wore black. Nick’s death followed a disciplinary action that some parents and school activists considered unnecessarily harsh. A school spokesman defended the district’s policies as appropriate and in line with state law.

Nick had been suspended two months previously for buying a legal drug at school called JWH -018, often called synthetic marijuana. Nick tried the drug at home, but the drug-seller, another student, apparently pointed him out to school officials.

Nick was banned from Woodson and thus cut off from his social circle, including the Boy Scout group to which he belonged. He eventually was permitted to enroll in another school, but on what would have been his sixth day there, January 20, he killed himself at his home.

Nick’s father, Steve Stuban, says the punishment contributed to his son’s death in that it robbed him of his support system, his identity and his friends, which caused him to sink into a deep depression.

The Post reported that in 2009 another Fairfax County high school football player, 17-year-old Josh Anderson, committed suicide as he awaited a hearing on a second marijuana offense.

On March 10, 2011, the Post ran a story about a 13-year-old girl undergoing a disciplinary process which had kept her out of her regular middle school for nearly two months. Her offense? Having acne medication in her school locker.

School to prison

In newspaper blogs in Texas this past year, Texas Supreme Court Chief Justice Wallace Jefferson is widely quoted as having said: “More than 80 percent of adult prison inmates are school dropouts. Charging kids with criminal offenses for low-level behavioral issues exacerbates the problem.” Whether Judge Jefferson claims these words or not, the observation is correct.

Annette Fuentes, author of Lockdown High: When the Schoolhouse Becomes a Jailhouse (Verso, 2011), wrote: “In California alone, there were more than 700,000 out-of-school suspensions in the last school year. And Texas had more than half a million.

“Each time a student is excluded from the classroom, it puts his or her education in suspension,” she wrote. “Suspensions lead to the school-to-prison pipeline. The harsh discipline of zero-tolerance policies puts the most vulnerable kids, disproportionately African-American and Latino students, at greatest risk of dropping out of school. And from there, excluded from education and with limited prospects, they are at greater risk of falling into jail.”

“Zero tolerance” refers to the way many school districts moved to absolute penalties and increased punishments for violations of weapon, drug and some other policies. Zero tolerance accelerated following the gun-killings of 13 in Columbine High School (Colorado) by two students in April 1999.

Turning the tide

Fairfax County Public Schools comprise the 11th largest system in the United States and are often a bellwether for the nation in education, given the system’s relatively wealthy tax base and prime location in the shadow of the nation’s capital.

A dozen or so restorative justice practitioners in northern Virginia, some of them trained at CJP, are trying to turn the tide in Fairfax County schools toward more humane, effective, and lasting results. CJP-linked practitioners include Vickie Shoap, the first “restorative practice specialist” hired by the Fairfax school system (beginning July 2011); Joan G. Packer, a district-court certified mediator formerly employed as the “conflict resolution specialist” by Fairfax schools; Packer’s successor Kristen W. (Packer retired in 2010 after 32 years of service to the schools); David Deal, vice chair of the Restorative Justice Project under Northern Virginia Mediation Service; and Natalie Thompson, who also works with the Mediation Service.

Packer supervised Dan Buescher, MA ’10, for an internship in the spring of 2010 doing restorative presentations, trainings and interventions within the Fairfax school system. “In 2002, I graduated from Woodson High School” – Nick Stuban’s school – “so this felt like coming home to me,” said Buescher.

One of the highlights of his one-semester internship, Buescher said, was participating in a two-day workshop on restorative practices attended by some of the administrators of Westfield High School (the largest in the state) and staff from five other schools.

Starting with the enthusiastic backing of Westfield vice principal Dave Jagels, Deal said there has been a gradual increase in referrals to facilitators trained in restorative practices. “A single case was handled at the end of the 2007-2008 school year,” he wrote on his website, www.dealwork.us. The next year, there were seven cases handled. Then the third year, 2009-10, 34 cases, with other schools joining Westfield in making referrals. This grew to 80 cases in 2010-11.

Increasing interest in applying restorative practices to schools was reflected in the third biannual National Conference on Restorative Justice in June 2011, where 18 percent of the sessions (13 out of 71) pertained to restorative justice in school settings.

In one of the sessions, Barbara McClung of the Oakland (Calif.) Unified School District explained: “The paradigm shift from zero tolerance to restorative discipline helped to successfully reduce fights and defiance, while lowering suspension rates by more than 80 percent.”

Nashville revisited

In an odd way, it was someone from the Oakland, California, school district that caused Chris Peak, MA ’11, of Nashville, Tennessee, to enroll in the master’s program at CJP. On an airplane several years ago, Peak happened to sit next to attorney Sujatha Baliga, an alumnus of EMU’s Summer Peacebuilding Institute and a key player in the shift to restorative discipline in Oakland’s schools. As the two chatted, she handed him a book by restorative justice pioneer Howard Zehr and told him about Zehr’s place of employment, CJP.

Jumping forward, Peak is now enrolled as a full-time master’s student at CJP. For his required practicum, Peak arranged to return to the conservative, private Presbyterian school from which he had graduated in 2003. He recalls that he spent much of his early teen years in trouble at that school – he now understands that he was angry over his parents’ divorce, but the anger came out in unhealthy ways. “I took on the identity of rebel and misfit,” he says.

Peak had a simple goal in returning to his old school: To show them how they could align their values – their professed love and concern for each child – with restorative practices, rather than retributive ones, which he felt hurt him years ago and no doubt many other young students before and since.

“They gave me 90 minutes for a teacher in-service, but they stayed for two hours. They didn’t want the session to stop. ‘This is what Jesus wants us to do,’ they declared.”

Unexpectedly, Peak found himself addressing gaps in the wider culture of the school. “I found the teachers didn’t feel cared for by the system, and the administrators didn’t feel cared for either, especially not by the church above them. So it wasn’t surprising that the students didn’t perceive themselves to be in a caring atmosphere.”

Centering himself on the Christian values that all subscribed to, Peak led components of the school and nearby church to take the time to sit in facilitated circles and to open their hearts and minds to each other.

“There had been no time set aside to simply communicate – local ownership of anything is time consuming,” he said. In just a couple of months, everyone was noticing positive changes in behavior and relationships. Says Peak: “They were developing a culture of care.”

[For further reading: The Little Book of Restorative Discipline for Schools (2005) by Lorraine Stutzman Amstutz and Judy H. Mullet // Discipline That Restores (2008) by Ron and Roxanne Claassen // “School-Based Restorative Justice: Ten Lessons Learned,” a paper by David T. Deal posted at www.dealwork.us]