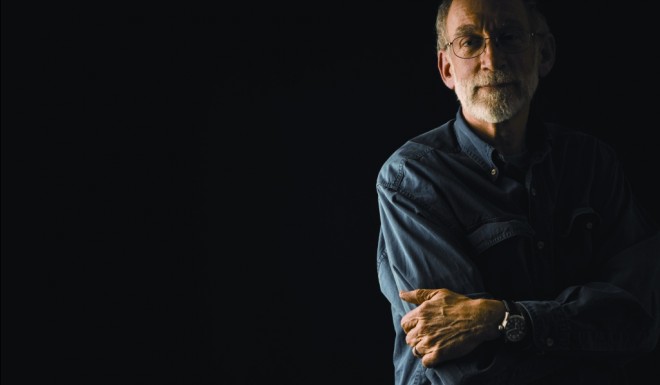

On Oct. 16, 2008, the United States Sentencing Commission held a “working luncheon” in Washington D.C., where EMU restorative justice professor Howard Zehr was the opening panelist. The following is a much-abridged version of what he said. Zehr is one of six appointed members on the commission’s Victims Advisory Group.

It’s an honor to be here… I’ve been given the task of giving a brief overview of restorative justice.

Restorative justice as a field developed in the 1970s. It developed in specific communities in the United States and Canada as an effort to deal particularly with three areas of concern.

One was the neglect of victims, and the traumatization or re-traumatization they often experienced in the justice process.

A second had to do with how we deal with offenders. We were convinced that offenders have deep denial processes, and that the legal system and the experience of prison tended to increase those denial mechanisms. We wanted a way to hold them accountable, in the sense of helping them to understand [the need] to take some responsibility for what they were doing.

And the third was the impact [on], and the involvement of, the community. We were concerned that justice not only did not reduce the tensions around the crime in the community, but often actually increased the conflicts and tensions around it. We felt that the community was often victimized and needed to have its needs addressed just like individual victims, but it also needed to be engaged in this process, and it needed to step up to the plate and accept its responsibilities.

So those are the kind of concerns that led to restorative justice.

The research has been encouraging. The latest meta studies from Sherman and Strang released in England looked at 36 studies from around the world and found high levels of victim satisfaction, reduced recidivism by most offenders, [and] greater understanding by victims and offenders of the other. They concluded that the research for restorative justice is much stronger than [for] many of the innovations that we’re spending billions of dollars on.

Restorative justice revolves around three basic principles:

One is that crime and other kinds of wrongdoing create harm, and harm always generates needs. That’s why victims have to be at the center of restorative justice.

Secondly, it has to do with obligations. All of our ancestors, I think, understood that when we harmed somebody, we had an obligation. That obligation was to try to put it right to the extent we can. The first obligation is the offender’s, but the community may have obligations as well.

And the third principle is the principle of engagement. As seen in some of the research, the more you involve victims and offenders in the outcomes, the more satisfied they are, and the more satisfactory the outcome.

Sometimes I say it really revolves around three questions. In the legal system, we tend to ask, “What laws were broken and who did it; what do they deserve?” Restorative justice is trying to think, well, there are three other questions that are important: “Who has been harmed in this situation? What are their needs? Whose obligations are they?”

When we first began, we began with more “minor crimes.” But today there are programs for the most serious kinds of crime and many new applications. There are [restorative justice] programs in every continent except Antarctica.

One of the most exciting arenas is school disciplinary procedures. The schools are beginning to realize that basically we’re mirroring the criminal justice system in our schools with zero tolerance, and so forth. It’s not working. And so more and more school systems are adopting restorative disciplinary processes.

For more information on restorative justice, read Howard Zehr’s pioneering book Changing Lenses – A New Focus for Crime and Justice, originally published in 1990, now in its third English-language edition, along with editions in six other languages. For a quicker read, check out his Little Book of Restorative Justice (Good Books, 2002).