Lithuania

Today is Sunday June 3, 2018. We all went to church and it was a good service. We just got back from our week-long trip to Vilnius, Riga, and Tallinn. It was very interesting to see the architecture and learn about the history about these cities. … Continue Reading ››

… Continue Reading ››

… Continue Reading ››

… Continue Reading ››

Exploring Paraguay: Asuncion to the Chaco

Montage of India

Through Post-neomodern Art

-Yelisey Shapovalov

I present to you the best of India through the art form that we millenials connect with most: selfies. My efforts began with the aspirations of sharing my adventures with my parents who are largely responsible for my being here; however, it turned out that they weren't … Continue Reading ››

India: Mussoorie, elevation 6,580 feet

Mussoorie Impressions

Mussoorie has carried with it more anticipation than any other stop on this trip for me. Although I enjoyed our racing around Rajasthan for two weeks, my mind and body were exhausted and looking forward to resting in one place for some time. As we boarded our third and final overnight train ride, I … Continue Reading ››

India: Rajasthan to Mussoorie

Dawn in Mandawa

Location: Roof of a Haveli in Mandawa, Rajasthan, India. 6:15 am.

The sound of music drifts through the brisk March air towards me from some unknown source. The city seems still and sleepy. Occasionally, I catch the moo of a cow and the chirp of a bird. Audible all around me is the sound of … Continue Reading ››

India: Rajasthan, Part II

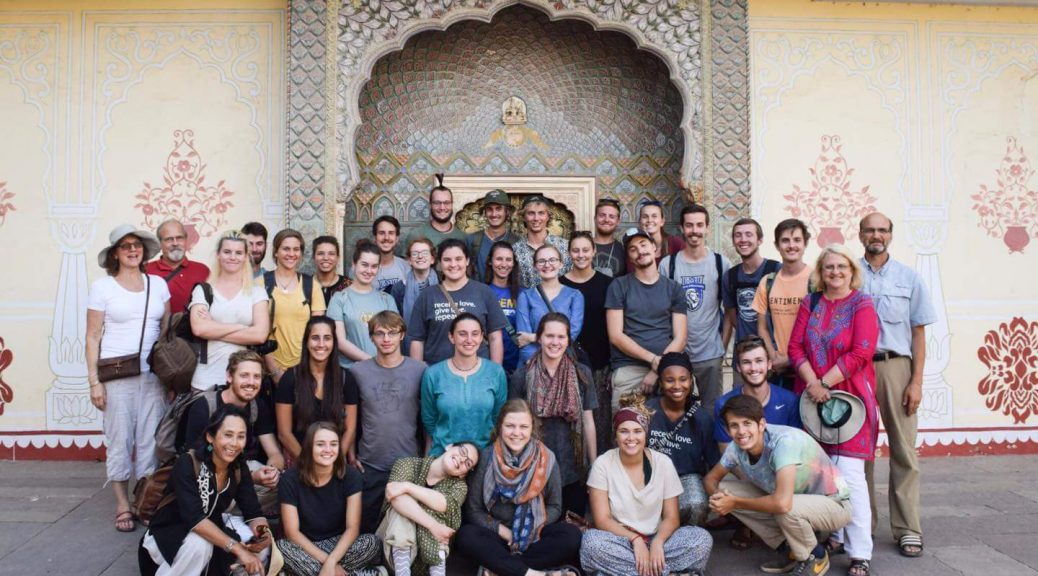

El Classico, or A Day in Jaipur

An account of perhaps the most comically representative full-day experience of our entire trip. It all began with a man wearing a straw hat and a winning smile who stepped onto our bus that morning and invaded our lives forever. "Goodmorningmynameis[incomprehensible]butyoucancallmeJiJi––" he said breathlessly. "It's a good thing you … Continue Reading ››

Independent travel in Guatemala and Belize

Free travel was supposed to be a well-earned vacation from learning; I was expecting to saunter off into the Guatemalan jungle and render my mind blissfully empty of deep thoughts. Yet, in the aftermath of our week-long adventure through the mountains of Cobán and the steamy lowlands of Lake Izabal, I’ve realized that I accidentally … Continue Reading ››

Rajasthan Overview

After our stay at the Sarang Center in southern India, followed by our spring break week, we traveled back to Delhi before heading into northwest India – into the state of Rajasthan. Rajasthan, in Hindi, means "land of kings" and is the ancient home of a collection of forts, palaces, fancy tombs, and Silk Road … Continue Reading ››

Kerala & Sarang Center

A day in the life at the Sarang Center, second person POV:

6:15 am: First alarm

6:20: Second alarm

6:22: Get out of bed, throw Kalari clothes on

6:31: Take Rickshaw to Kalari

6:47: Arrive, lather oil on body, go through bowing routine

7:01: Smile and grimace after Guru-ji starts class with “Three laps!, one more, one more!”

8:30: leave class a … Continue Reading ››