4 November 2019

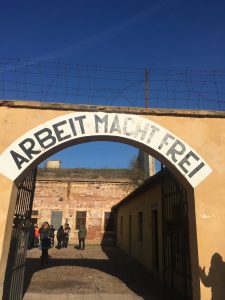

When we started learning about the Holocaust in Europe, specifically in Vienna, I felt like being American, being so far removed from these tragedies, had made it difficult to understand them until I was there in the countries where they took place. It impacted me greatly to be standing in the plaza where Adolf Hitler gave speeches to cheering crowds or at the hotel he stayed in. On Thursday, we visited Terezin, a former military fortress that following Nazi occupation of [Czechoslovakia] during World War II was turned into a Jewish ghetto and concentration camp. After that experience, I think that being from across an ocean was not the only thing stopping me from really understanding the Holocaust. You could be from the Czech Republic, or Austria, or even Germany, but it’s not until you stand in the dark empty cells that held so many people they were forced to sleep standing up, that the gravity and the terrifying reality of the Holocaust really sinks in.

While Terezin was operating as a concentration camp and ghetto, it took on more than 150,000 Jewish prisoners. Of these 150,000 people, over 33,000 died because of the conditions such as hypothermia, starvation, untreated health problems, and physical abuse. Eighty-eight thousand were sent on to Auschwitz or other death camps to be killed. Even though it wasn’t labeled an extermination camp, there were only 17,247 survivors of Terezin by the end of WW II.

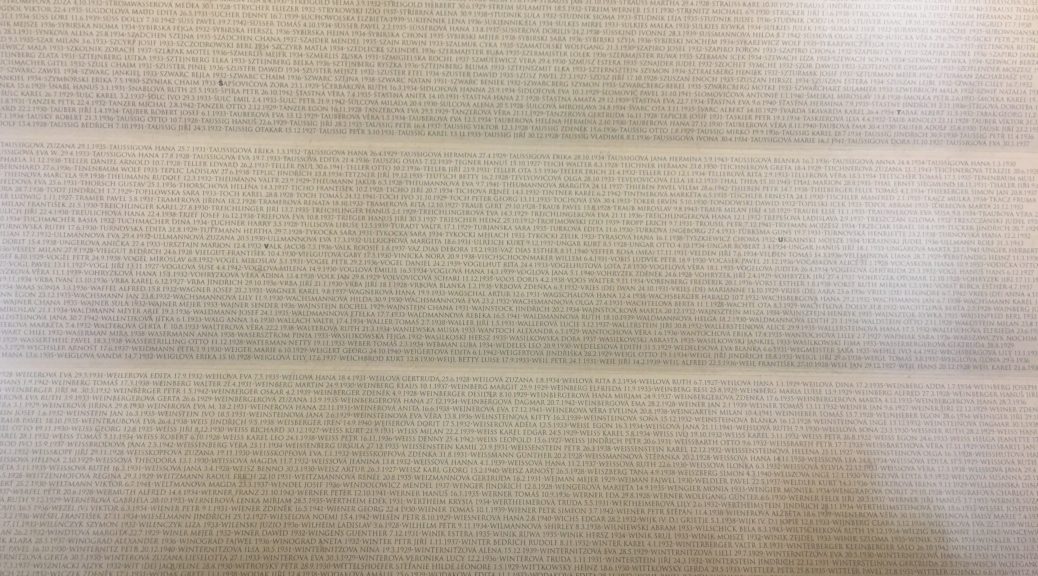

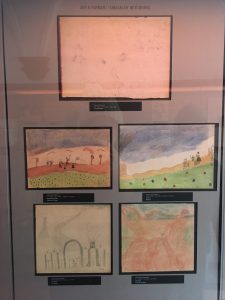

I could talk about the awful stories of torture and abuse from inside the concentration camp, but what affected me the most was the children’s memorial in the accompanying museum. 15,000 children spent time in Terezin, living life as best they could amid the most unimaginable conditions. For children, this means drawing. In the museum were displayed hundreds of drawings found after WW II made by the children. They ranged from idyllic family pictures and drawings of home, to conditions in the ghetto, even to depictions of the abuses they and their parents were suffering at the hands of the guards. And under each one, there was a name and either the word survived or a death date with the camp they were killed at. On the walls of the display were printed the names of every child killed from Terezin, most under the age of 13.

Only 130 children out of 13,000 made it out of Terezin alive, a 1% survival rate. It is hard for me to process the dehumanization that must happen for a grown adult to look a child in the eyes and throw away their life. I can’t help but think about how this process starts, what the seed of distaste looks like that eventually grows into hatred so strong it blinds you to humanity.

Only 130 children out of 13,000 made it out of Terezin alive, a 1% survival rate. It is hard for me to process the dehumanization that must happen for a grown adult to look a child in the eyes and throw away their life. I can’t help but think about how this process starts, what the seed of distaste looks like that eventually grows into hatred so strong it blinds you to humanity.

The root cause of travesties like the Holocaust is elusive. Maybe it is complacency, people doing what they’re told to avoid rocking the boat. Maybe it is fear of the unknown and deciding it is safer to eliminate differences rather than try to get to know them. Maybe all it takes is a charismatic leader whose promises of a greater tomorrow are just promising enough to give desperate people enough hope they’ll do anything to get there. Whatever it is, it is worth acknowledging that the potential for hatred is inside all of us. While I desperately hope this hatred will never again take on a form like Holocaust, the instinct to exclude, isolate, and dehumanize people different from us is volatile if gone unchecked. And, maybe you don’t have to go to a concentration camp to realize that, but it makes it a lot more obvious.

-Kate Stutzman