Bumping along in our small, faulty-but-still-chugging bus driven by Baba, with mini Table Mountains lining the landscape of our three-day trip from Joburg to Capetown, we compile this blog, attempting to blend together these many thoughts from the past week. We’ve decided as a group to release this first week of learning over the course of four blog posts, focusing on the essential themes. Not only do we welcome your questions, but we ask for them. We will read them as a group, discuss, and answer as best we can; we’re excited to say we’re looking forward to starting the conversation.

This has been a week of seeing Soweto through the wrinkled eyes of its majority rather than through the tints of its flashy few. Coming from the lifestyle of privilege that is normal in the United States, it is so easy to magnetize to it in any new context we find ourselves… and globalization has made it so that we could access it anywhere in the world. It takes organizing and preparation to travel somewhere else in the world and plan a trip of honest encounter with the Other, an encounter of intentionality. I feel grateful to have leaders who know the context of South Africa well enough in this way to craft a cross cultural that illuminates the reality of the (black) majority, while intentionally juxtaposing the lifestyle of those who have convinced themselves to believe they’re above it. (system?)

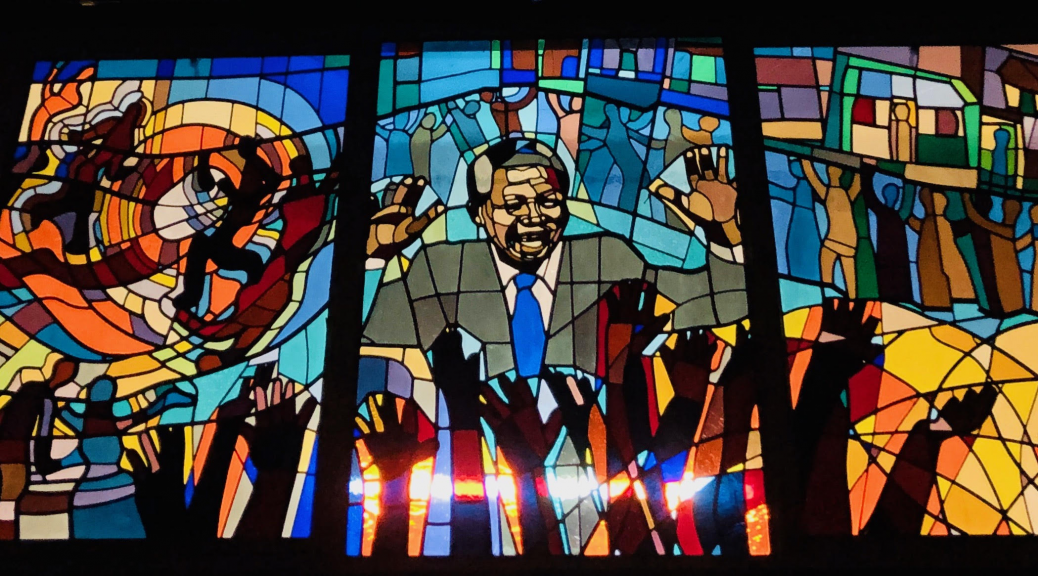

The Apartheid Museum and insight provided by those who are guiding us through, including South African pals connected through the Anabaptist Network in South Africa (ANiSA), laid a foundation for understanding apartheid in South Africa (SA). This is a system strategically set in place in the early 20c to impart hate, to divide, and to confuse, so that the black majority would never have more power than the Afrikaner minority. Having at least some basis coming in to SA, a question many of us had coming in was: how similar or different is the people’s history of racial discrimination in SA to that of the US? A few gleanings learned from this past week made the answer to this question clearer:

- A similarity: The native makeup – there are 11 official languages and in the regions we’ve been to so far, you can usually assume a black person is either tribally Zulu, Xhosa, or Sotho. Most people speak far more languages than my mere one, which allows for translating and compromising. Our host mom said she is usually the one to compromise in a conversation – when she hears that the person’s accent is Xhosa she’ll switch from her native tongue of Zulu to Xhosa; when she hears a Sotho accent, she’ll switch to Sotho. Communities like the one in Orlando of Soweto that we stayed in are a “mixed masala” she says – all black ethnicities live on one block. In the US context, this is most similar to the Native American population with its multitude and diversity of tribes and cultures, comprising the first population to live on American soil. Similarly, Native Africans were on African soil for centuries prior to any white man stepping foot on it, sustaining thriving kingdoms and knowing the land and its resources as their own.

- A difference: The system of apartheid was socially engineered – “perfect racism”, says Trevor Noah. The Afrikaner of SA felt threatened by the black majority of nearly 80%. The government therefore travelled to and studied other instituted systems of racism around the world – in Australia, in the Nazi regime, and in the US and Canada. “Then they came back and published a report, and the government used that knowledge to build the most advanced system of racial oppression known to man.” Land rights became one of the main ways that apartheid was installed and established, despite the irony of true black ownership of the land (insert pic) Overall, there were over 3 thousand pages of laws written to suppress the agency and power of Black, Colored, and Indian people; a new law was created in reaction to any time a non-white person attempted to squirm free from the system.

- A difference: The US has never had anything like the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), for the deep harm that colonialism drove into the natives it subordinated, abused, and killed. We mainly learned about the TRC through Desmond Tutu’s book No Future Without Forgivenessand Pete Meiring, a TRC commissioner who spoke with us about his reflections and experiences on the commission. In wondering how to go about moving forward as a nation post-apartheid, brainstormers who were mainly theologians discussed whether it was preferred to have this process look more like Nuremberg (the typical retributive justice way), amnesia (forgive and forget), or a third way. That third way became “granting amnesty to individuals in exchange for a full disclosure relating to the crime for which amnesty was sought” (30). Tutu emphasizes that the basis of this third way is the concept of Ubuntu, which “speaks of the very essence of being human”, saying “I am human because I belong. I participate. I share.” “A person is a person through other persons; in other words, “my humanity is caught up, is inextricably bound up in yours” (31).

The interconnection of black struggle, around the world, became glaringly clear throughout this week. From the Foreword of a required reading by Steve Biko entitled “I Write What I Like,” which explores his philosophy called Black Consciousness:

The interconnection of black struggle, around the world, became glaringly clear throughout this week. From the Foreword of a required reading by Steve Biko entitled “I Write What I Like,” which explores his philosophy called Black Consciousness:

Biko’s Black Consciousness (in which the term “black” includes all people of color) stands on the shoulders of this history. It is grounded in the recognition of the high costs of truth. Biko wants the people, all people, to seewhat was going on in South Africa and all over the world. He wants us to see the connections between South African black townships, the black ghettoes in England, the United States, and Brazil, and the many similar communities in South Asia and the Middle East. Many of us share his insight today when we seek those whom we call ‘the blacks’ of their society, even if they may not be people of African descent.