10/16/18

“Are you Christian?”

“Are you Mennonite?”

Every time I’m asked these questions, I usually respond with a sputtering “well I was raised Mennonite”, or even a resounding yes to bring a quick end to an uncomfortable conversation. However, neither answer really felt like an honest portrayal of my uncertain religious convictions.

In the West, we expect a simple yes or no to these questions. To us, religion is a binary: either you are or you are not. This expectation of exclusive belief makes discerning religious and spiritual ideas difficult; how can we figure out our beliefs when there is no room for grayness in religion?

In China, however, religion is nothing but gray. Religion (or philosophy, depending on your definition of religion) in China does not necessarily mean complete faith in one religion but can be a personal combination of many thoughts. Therefore, it is nearly impossible to find accurate numbers for people in China who

consider themselves religious by Western standards. Someone may consider themselves non-religious but still pray for prosperity if they visit a Christian church or Buddhist temple. Or, one may consider themselves religious but believe in any combination of Confucianism, Daoism, Buddhism, etc., and practice in any kind of various ways. (This disbelief in exclusive religion is one of the reasons Christianity struggled for centuries to find its place within Chinese society).

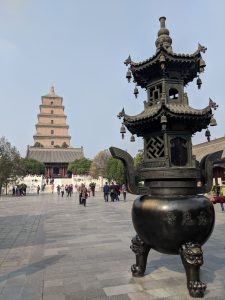

This past Monday, we visited a Daoist temple, Nestorian Christian pagoda and a Buddhist pagoda/temple (all dating back to at least the seventh century CE). Normally, when discussing religion, we try to organize and classify each thought, finding differences between every religion. Visiting three different religious sites in one day, however, enabled me to see the similarities. The Buddhist and Daoist temples each were similar in composition, with classic Chinese architecture, inscribed paintings and figures to venerate. The pagodas at the Buddhist and Nestorian sites were similar in shape and size, and inside the Nestorian pagoda, Daoist and Christian iconography intermingled. If the places of worship were so similar, then surely the beliefs must be in some way as well.

While I walked among the Daoist buildings within the temple walls, each decorated with beautifully bright paintings of nature and in the courtyards wafting with incense, I felt at peace. This feeling of connectedness was greater than anything I have ever felt in a church or at any of the European Anabaptist sites I visited last summer.

Perhaps this sense of peace I felt in the Daoist temple was the spiritual connection I yearned to have out of guilt for lacking the deep faith others’ possessed, but I eventually shunted, out of self-perceived failure and anger.

I have never felt comfortable answering yes or no to inquiries about my Christian faith, but maybe it is because a simple yes or no cannot properly convey my faith. China, and this cross-cultural, have given me a new and open space to explore my spirituality that no where else has and tools to process my complicated relationship with religion that I have yet to find exclusively within the Christian church. For this I am thankful.

I am not ready to turn my back on the Mennonite church, but I need more. While I have yet to reach any conclusions on how I identify religiously, I am no longer sure I want a definitive answer. In some ways, I am more comfortable without clarity. Ultimately, I think the Chinese may have it right: why strictly follow one doctrine when you can syncretize so many beautiful philosophies? Why be religiously stagnant when there is so much to explore?

-Emma Yoder